As someone who makes his living in a world populated by paper, ink and staples, I found the Newsweek news both significant and unsurprising. The death of the print edition was considered inevitable; it wasn’t a question of if, but when. Now, people are dissecting the cadaver.

Jeremy Lott notes:

With today’s news that Newsweek will officially quit printing at the end of the year, many many critics will pile on to editor Tina Brown, blaming her for the newsweekly’s demise.

And make no mistake, this is a demise. The Daily Beast, which predates and is different from Newsweek, is the Internet face of that enterprise. There is no good reason to split the brand. Even if Newsweek retains some Internet presence, it will shrink to nothing before long.

Brown didn’t save Newsweek, but she didn’t set it on its death march either. Her tenure as editor was more like very buzz-filled hospice care. She tried to reinvigorate it with Girl Power, and that didn’t work. She tried bringing in names like Andrew Sullivan and David Frum to get more subscribers. Again, a flop.

None of those things would halt the decline, but let’s remember who really pushed the magazine over the cliff: previous editor Jon Meacham.

He goes on to explain why. But Newsweek/Daily Beast vet Andrew Sullivan has a different take:

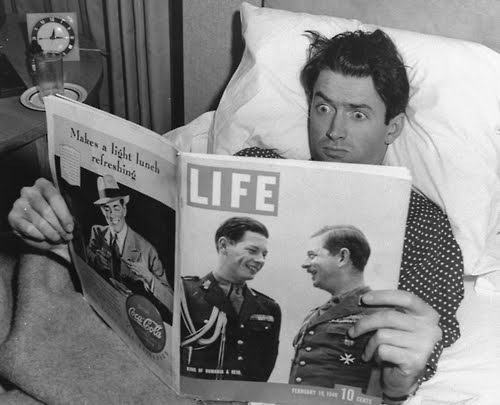

One day, we’ll see movies with people reading magazines and newspapers on paper and chuckle. Part of me has come to see physical magazines and newspapers as, at this point, absurd. They are like Wile E Coyote suspended three feet over a cliff for a few seconds. They’re still there; but there’s nothing underneath; and the plunge is vast and steep.

Which is why, when asked my opinion at Newsweek about print and digital, I urged taking the plunge as quickly as possible. Look: I chose digital over print 12 years ago, when I shifted my writing gradually online, with this blog and now blogazine. Of course a weekly newsmagazine on paper seems nuts to me. But it takes guts to actually make the change. An individual can, overnight. An institution is far more cumbersome. Which is why, I believe, institutional brands will still be at a disadvantage online compared with personal ones. There’s a reason why Drudge Report and the Huffington Post are named after human beings. It’s because when we read online, we migrate to read people, not institutions. Social media has only accelerated this development, as everyone with a Facebook page now has a mini-blog, and articles or posts or memes are sent by email or through social networks or Twitter.

And as magazine stands disappear as relentlessly as bookstores, I also began to wonder what a magazine really is. Can it even exist online? It’s a form that’s only really been around for three centuries – and it was based on a group of people associating with each other under a single editor and bound together with paper and staples. At The New Republic in the 1990s, I knew intuitively that most people read TRB, the Diarist and the Notebook before they dug into a 12,000 word review of a book on medieval Jewish mysticism. But they were all in it together. You couldn’t just buy Kinsley’s perky column. It came physically attached to Leon Wieseltier’s sun-blocking ego.

But since every page on the web is now as accessible as every other page, how do you connect writers together with paper and staples, instead of having readers pick individual writers or pieces and ignore the rest? And the connection between writers and photographers and editors is what a magazine is. It defines it – and yet that connection is now close to gone. Around 70 percent of Dish readers have this page bookmarked and come to us directly. (If you read us all the time and haven’t, please do). You can’t sell bundles anymore; and online, it’s hard to sell anything intangible, i.e. words, because the supply is infinite. You no longer control the gate through which readers have to pass and advertizers get to sponsor. No gateway, no magazine, no revenue – and massive costs in print, paper and mailing.

The reasons, I guess, are many and varied, but Sullivan does pick up on one key point: the number of people reading ink on paper is dwindling—and the rate at which it’s happening is accelerating. My morning subway ride is dominated now by people with Kindles and iPads, not newspapers and paperbacks; if they aren’t reading the morning paper, they’re playing Angry Birds. (Me, I’m usually praying the Liturgy of the Hours, which is easier while one hand is holding a metal bar and another a tablet than it is when you have to turn the pages of a leather-bound book…)

It’s a different world. And I can’t help but feel that more magazines—and newspapers—will soon be joining Newsweek in the digital realm.