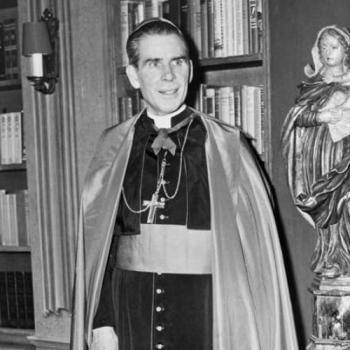

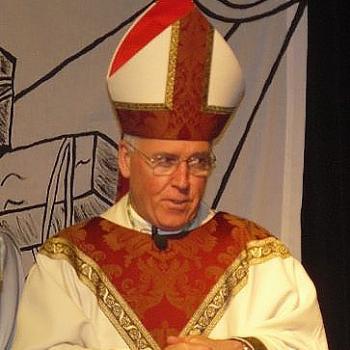

Their names are Mahony, Brown, Niederauer and Levada, and they were all in seminary together. Whatever happened to them?

Read on, from the Salt Lake Tribune:

Whether by accident, serendipity or divine design, four future heavyweights of American Catholicism found themselves in the Class of 1962 at St. John’s Seminary on a lush hillside 60 miles from Los Angeles.

Momentous societal changes were surfacing all around the young men, but seminary life for George Niederauer — who served as Utah’s bishop from 1995 to 2006 — and pals Roger Mahony, William Levada and Tod Brown continued much the same as it had since, oh, the 16th century. Part spiritual boot camp and part modern-day monastery, the school and its choreographed schedule stretched far beyond normal college rhythms — a Catholic “Goodbye, Mr. Chips.”

The four friends — a pair of cardinals-to-be, a future archbishop and bishop — were assigned alphabetically to desks and dorms. They arose at 5:30 a.m. to the blare of an insistent hallway bell, and, within a half hour headed to the chapel for prayers and Mass. Silence was required during meals and after 7:30 p.m. Moral theology and philosophy classes were taught in Latin.

The priests-in-waiting had neither televisions nor telephones and were forbidden to leave the Camarillo, Calif., campus without permission. They could read about current events — such as the 1960 election of the first Catholic to the White House — but only in clips from approved newspapers.

They knew little of the simmering anti-authoritarian and anti-war sentiments percolating on college campuses, the rock music that would burst onto the scene with the Beatles or the looming sexual revolution.

Released from their Catholic cocoon in 1962, the young priests faced a church on the brink of volcanic reform with the opening of the Second Vatican Council, pushing the ancient institution into a new age. No more Latin Mass. Priests now faced the people, not the altar. Other Christians were embraced, and social work became gospel.

After being schooled in a Vatican I church, the foursome would step down, five decades later, as quintessential Vatican II men.

“There was no instruction manual with a chapter [to cover] every conceivable crisis for the next 50 years,” says Mahony, who rose to archbishop of Los Angeles, his home turf and the nation’s largest Catholic archdiocese.

And there were many unexpected twists — a precipitous decline in priests and nuns, growing divorce rates, the push for reproductive rights and gay rights, an increasingly ethnic population, widespread disaffection and school closings, and, of course, the priest sex-abuse scandal.

Niederauer, Mahony, Levada and Brown were gifted, dedicated men whose skills were recognized early and tapped often.