If you are one of those who has forsaken Facebook or Twitter for Lent, you might want to ponder these thoughts from Casey N. Cep in The New Yorker, writing about the recent National Day of Unplugging:

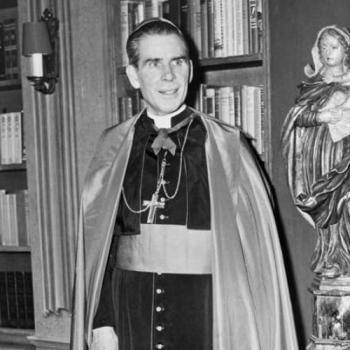

I was struck last year when Pope Benedict XVI, after he started tweeting, delivered a message on social networks. “The exchange of information can become true communication, links ripen into friends, and connections facilitate communion,” the Pope said. He added that, with effort, “it is not only ideas and information that are shared but, ultimately, our very selves.” Perhaps most surprisingly, the Pope argued, “The digital environment is not a parallel or purely virtual world but is part of the daily experience of many people, especially the young.”

In that way, the unplugging movement is the latest incarnation of an ageless effort to escape the everyday, to retreat from the hustle and bustle of life in search of its still core. Like Thoreau ignoring the locomotive that passed by his cabin at Walden Pond or the Anabaptists rejecting electricity, members of the unplugging movement scorn technology in the hope of finding the authenticity and the community that they think it obscures.

Unplugging seems motivated by two contradictory concerns: efficiency and enlightenment. Those who seek efficiency rarely want to change their lives, only to live more productively; rather than eliminating technology, they seek to regulate their use of it through Internet-blocking programs like Freedom and Anti-Social, or through settings like Do Not Disturb. The hours that they spend off the Internet aren’t about purifying the soul but about streamlining the mind. The enlightenment crowd, by contrast, abstains from technology in search of authenticity, forsaking e-mail for handwritten letters, replacing phone calls with face-to-face conversations, cherishing moments instead of capturing them with cameras…

…Few who unplug really want to surrender their citizenship in the land of technology; they simply want to travel outside it on temporary visas. Those who truly leave the land of technology are rarely heard from again, partly because such a way of living is so incommensurable. The cloistered often surrender the ability to speak to those of us who rely so heavily on technology. I was mindful of this earlier this month when I reviewed a book about a community of Poor Clares in Rockford, Illinois. The nuns live largely without phones or the Internet; they rarely leave their monastery. Their oral histories are available only because a scholar spent six years interviewing them, organizing their testimonies so that outsiders might have access. The very terms of their leaving the plugged-in world mean that their lives and wisdom aren’t readily accessible to those of us outside their cloister. We cannot understand their presence, only their absence.That is why, I think, the Day of Unplugging is such a strange thing.