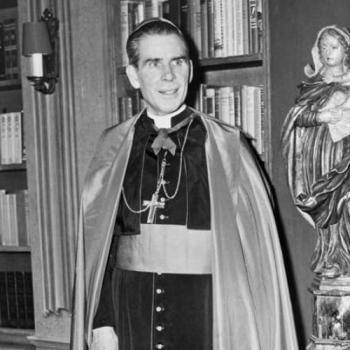

Twelve years ago, when I began formation, the director of the diaconate program was a short, wiry, affable Italian with piercing eyes and boundless energy known simply as Father Frank. He was a force of nature, and among the most gifted priests I’ve ever met—brilliant, generous, compassionate, prayerful. The men in my huge class—52 of us—absolutely adored him. You knew he was the real deal.

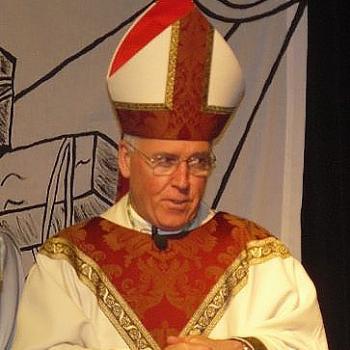

Now, Fr. Frank is Bishop Frank, the Bishop of Bridgeport. All the qualities we knew and loved in Brooklyn are being put to use in Connecticut—and people are taking notice.

Last week, my pastor slipped into my mailbox at the rectory the latest issue of the National Catholic Reporter and there, splashed across the front page, was a profile of Frank Caggiano. The Bridgeport diocese has just posted the story online. It’s long, but it’s worth the read. It gives a balanced (but highly favorable) glimpse at a man who is Brooklyn’s gift to Bridgeport.

“He’s a breath of fresh air,” said Paul Lakeland, the Aloysius P. Kelley, S.J. Chair in Catholic studies at Fairfield University.

Other Bridgeport Catholics interviewed added “inviting,” “humorous,” “sincere,” “good listener,” “relatively fearless,” “Vatican II” and “entirely un-image-conscious” to his description.

“It’s boringly good,” Lakeland said.

The common explanation is that Caggiano carries himself in a way that’s more approachable than his predecessors, more ordinary than ordinary.

“If you see him out on the streets, and you run into him, he’ll talk to you like there’s nothing else that matters at that moment,” said Florencia Silva, head of the diocese’s pastoral services office. She described him as cercano, a Spanish word meaning “close to the people.”

The closeness is evident in the ongoing marathon of meetings and listening sessions in and outside his office that have filled his schedule since his arrival. He’s met with donors, prison reform advocates, the Newtown community and even the local Voice of the Faithful chapter. Additionally, he set aside time specifically to meet with his priests, giving them his personal contact information with a straightforward request: Call me anytime. So far, more than 100 of the diocese’s 240 priests have taken up the offer.

The outreach has brought a renewed energy to the presbyterate in a diocese where a few years ago, morale was low and enthusiasm even lower, said Fr. Michael Boccaccio of St. Philip Church in Norwalk. Now, Boccaccio sees his brother priests more engaged, particularly at meetings where even new faces have begun to appear.

“There’s a welcome to openness and to a dialogue, and I’m seeing priests become more enthusiastic about their involvement and their criticism or questioning of the bishop,” Boccaccio said.

From the priest meetings, Caggiano has “learned their struggles and the struggles of the parishes.” Some, like Boccaccio, have expressed that administrative duties and financial struggles have created a vacuum in their pastoral ministry.

“Please, please, please let us be priests,” Boccaccio said.

Caggiano has heard that plea, calling it one of the greatest challenges priests have articulated, particularly in the desire and struggle to reach out to distant Catholics. He has also learned of priest isolationism, and wonders aloud if communal rectories might be a solution. Such a step, though, would have to come through the synod process.

So far, criticisms of Caggiano haven’t been few and far between—they’re nearly nonexistent, with concerns largely limited to doing too much, too fast, too soon for the diocese, as well as for his own good. In March, the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests called for him to commission an independent investigation related to two priests accused of abusing in the late 1960s and ’70s, and to publish names of abusers on their website. The diocese is working to publish the list, and Caggiano has communicated informally with several SNAP members.

Bridges to Rome

As noticeable as what Caggiano has done is who he is.

In describing their bishop, people cannot help but draw similarities between him and Pope Francis. First, there are the names. Both have called synods and both were born in the Americas to Italian immigrants. Beyond the superficial, people have witnessed parallels in style.

“He represents in some ways the new kind of bishop that Pope Francis is looking for,” Jesuit Fr. Jeffrey von Arx, president at Fairfield University, told NCR, listing simple living, a commitment to evangelization and a faithful message of compassion, forgiveness and engagement.

The confluence of Caggiano and Francis, von Arx said, came together at the right time.

“People are looking for a much simpler delivery of the Christian message, a much more kind of faith-based Christo-centric understanding of Christianity,” he said.

The connections make Bridgeport appear closer to Rome, where people can hear what Francis says at the Vatican and then see it lived out in their own neighborhoods.

Like Francis, Caggiano stands firmly in line with church teaching on marriage, ordination and other familiar reform issues, and, when asked, will share his thoughts. But also like Francis, the emphasis is placed elsewhere. He appears more interested in the pastoral development of his diocese than in making statements on hot-button issues. That style diverges from Lori, who became a national point person for the bishops in the religious liberty debate.

But those who have known Caggiano from Brooklyn and before say the Francis parallels are not the result of mirroring; it’s just who Frank has always been.

Born on Easter Sunday, Caggiano grew up on Van Sicklen Street in Brooklyn. It was there around the kitchen table he developed much of his personality, style and ministry — aspects he attributes to his parents. From his father, he learned that familial bonds hold strong, even amid disagreements; from his mother, he learned to listen. His preference for dialogue, he said, keeps him informed and engages others as partners.

“I need to be the guardian of the life of the church. … But that doesn’t mean I have all the answers,” he said.