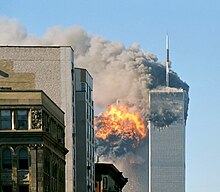

I’m not sure whether Fordham University is the first Catholic college to develop a program for international humanitarian action, but it had better not be the last. According to The New York Times, the number of schools offering degrees in respose to natural and man-made disasters has more than tripled over the past ten years — from 70 in 2001 to 232 today.

The programs emphasize various aspects of disaster relief, including psychological first-aid for survivors to . SUNY New Paltz’s program offers field trips to real disaster areas, and internships where studednts where students work in 9/11 call centers:

At the sleek new Emergency Services Center in nearby Orange County, where student interns from New Paltz shadow 911 call takers, the crises on a showery afternoon in mid-May were decidedly less grave. Ms. Rodriguez, who has since graduated, listened as Cristina Facchini took a call from a woman who was frantic because her neighbor’s pig had climbed on her car.

“She was inside the car and she stated that there’s a pig on top and he’s eating my car,” Ms. Facchini said moments after the call. “She wanted to move her car but didn’t want to hurt it. Apparently, it was a big pig.”

During their visit to the emergency center, Ms. Rodriguez and the other interns moved to a conference room and took turns deconstructing famous catastrophes: what Shannon Fisher, the county’s emergency management program coordinator, jokingly referred to as the “disaster du jour.” Among them were Love Canal, the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, the 2004 school hostage crisis in Russia and the 2005 train collision in South Carolina.

“I like getting a thorough history of disasters: what went well, what didn’t go well,” said Ms. Yates, a third-year student from Willow Spring, N.C. “Lessons learned is a big thing for me.”Then Ms. Fisher pulled out an envelope full of paper slips on which she had written the names of disasters to be discussed the next week. One by one, the students reached inside, drawing the European heat wave of 2003, the 1911 Triangle shirtwaist factory fire, and the tornado that killed seven children at an elementary school in Orange County, N.Y., in 1989.

Ms. Fisher urges the interns to use liberal doses of humor as a hedge against despair. So on the slip for Hurricane Katrina, she simply wrote, “You’re doing a heck of a job, Brownie.”

I don’t think I’ve ever been so proud of my dad as I was a few days after 9/11, when he told me he’d taken a few hours off from his psychoanalytic practice, strolled down to a nearby FDNY substation, and offered free grief counseling to the men. No invitation, no preparation — he just stuck his head though the door and said, “I’m here to help, if anyone needs me.”

I’m not sure I’d have been able to do the same thing. I suppose I’d have expected firefighters to share Tony Soprano’s aversion to therapy: “This all sounds very gay. I hope you’re not saying that.” In the event, a number of New York’s Bravest jumped at the chance for catharsis. My dad told me he felt pretty confident he’d helped them work at least part of the way through some difficult things.

That was only a couple of hours — granted, for my dad, a couple of very billable hours — but still, one part of one day in a life. Anyone who wants to do that sort of thnig for a living is a beautiful human being.

And, perhaps, a haunted one. The three SUNY students mentioned by name in the Times article were all driven toward careers in disaster relief by their own early experiences of various disasters — one had a close-up view of 9/11, two others had survived hurricanes. The Times writes:

“This generation has never known a time without terrorism or disaster, and I think it has drawn many of them to this field,” said Karla Vermeulen, deputy director of the Institute for Disaster Mental Health, which was founded in 2004 at SUNY New Paltz. “They were 10 at the time of 9/11 and 14 during Katrina, and it’s really shaped them.”

That’s a damned sobering thought. Anyone looking to get inside the head of millennials, or Generation Next, or whatever you want to call these young jackanapeses, should bear in mind that they see the world as a dangerous place. But unlike members of the so-called Lost Gneration, this knowledge hasn’t turned them cynical. In contrast to first generation to grow up after Hiroshima, they’re not fatalistic or wildly anti-authoritarian. Judging by this group of SUNY students — not to mention those of their age-mates off fighting in Afghanistan — they see the danger as confrontable and containable.

Nice bunch of kids.