Historically, many considered talk about heaven, or the heavens above, to be a purely physical place, that is, outer space, and it is the place Christ is to be found after his ascension. They believed that Christ reigns in glory in the heavens above us all, looking down upon us, and if we could make our way there, we would be with him. It is also where Enoch, Elijah, and Mary are also to be found. While a popular, and probably for centuries, the most common way people interpreted the heavens, there were others, especially those philosophically or theologically educated, who did not accept such a simple take. They believed the use of the heavens in Scripture and tradition was metaphoric; they accepted, in general, the same cosmology of their peers, but they thought the use of the heavens above was meant to serve as an analogy to the new modality of being which is to be had by those who enter in the kingdom of God and are glorified in it. That is, just as the heavens above were understood to transcend the earth, so the kingdom of God, “heaven,” transcends our current mode of being. How much space exists beyond the earth, most could not say. Some thought it was limited, others considered it potentially infinite, but no matter how much space they believed existed, they thought there were different heavens, each one transcending the one beneath it, allowing for further and further transcendence in the material realm; those who understood heaven as a metaphor suggested that this meant those in the kingdom of God will be able to continue to develop and grow, to constantly transcend themselves throughout eternity. Similarly, as Thomas Hopko pointed out, since the heavens above surround the world we live in, so God is said to surround all things (even as God is found in and able to be experienced in all things):

The statement that the Father is “in heaven,” or literally “in the heavens,” means that He is everywhere and over all things. The heavens are over all and encompass all. Wherever man goes on the earth or in the air, or even in space, the heavens are around him and over him. To say that the Father is “in the heavens” means that He is not tied down or limited to any one location—as were the gods of the heathens. The heavenly God is the “God of gods” (Deut 10.17, 2 Chron 2.5), the “Father of us all, who is above all and through all and in all” (Eph 4.5), the one in whom “we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17.28). To say that God is “in heaven” is not to place Him somewhere; it is rather to say that He transcends all things and yet is present to all.[1]

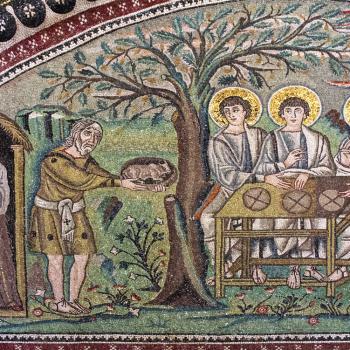

Scripture is written in a style which is far different from modern, positivistic forms of writing. Throughout, even in texts which tend to be literal (in the modern sense of literal), it is never free from poetic diction and the mythic mindset of the past, especially when the text is dealing with a theological or spiritual concern. This is why those who do not understand the poetic diction, and how to engage it, will misunderstand Scripture, as they will tend to read poetic or mythic descriptions and metaphors literally, and it is such literalization of the text which has led many Christians (and non-Christians) astray. Even texts which at one time could be taken literally often had a non-literal application, and it is that application which Christians believed they must be embrace. Thus, when dealing with its use of the words “heaven” and “heavens,” we should engage them as we would do with all poetic diction, knowing that the ancient cosmology the writers used has been utterly overturned by science. This allows us to still learn from Scripture and not be led to think Scripture is false since astronauts did not find Jesus, Enoch, Elijah, or Mary when they left the earth. This is also how we can answer those who have asked where God is, now that God was not found by those going out into space. To be sure, God can be found in space, if one looks for God in the right fashion, but God is found there in the way God can be found in and through the world itself – we come to know and experience God through the works of God, especially the way God has created all that exists. Everything, in their existence, participates in God’s existence, and in and through that participation, partakes of a quality of God themselves, allowing them to imagine or represent God, each in their own unique way. Those who did not find God in space did not find God because they did not know how to properly find God on earth, while those who know how to find God on earth see the work of God in space and so can and do find God in the heavens, even if they do not go there themselves. One way this truth is presented to us is in and through iconography; in icons, the saints are shown to exist in the kingdom of God, calling us to follow after them, and experience the kingdom of God, not just when we die, but while we live:

In the icon, personages and events are considered to be in heaven. They live and more in the kairos of God, every flowing, ever present, in “spiritual space.” They are in heaven and lead us to heaven. It is from the Holy Spirit and in the Holy Spirit that they acquire infinite extension and duration, and it is the Holy Spirit who endows them with the grace to be present and to be real. Because the Holy Spirit cannot be confirmed or limited in a physical space, they also are free from physical confinement and limitation.[2]

Because of the way the words “heaven” and “heavens” can be interpreted as being either the physical space which lies beyond the earth, or the kingdom of God, much confusion often ensues when the term heaven is used. This has certainly been the case throughout Christian history. Sometimes people mean the kingdom of God when talking about heaven. Sometimes people mean outer space. Sometimes, people equate the two, but other times, people view them as analogues to each other. Due to the confusion and equivocation which can occur, it is often best to speak of the kingdom of God and not heaven, unless dealing with ancient texts. Nonetheless, it is important to point out how ancient writers, including those who wrote various texts found in Scripture, might have equated the two. Just as Jonah preached the truth and got things wrong in his understanding of it, so we can accept the writer of a text was wrong in their cosmological understanding while believing that the text can and still does promote an authentic theological teaching. This is also why we should not be concerned with the way ancient writers viewed the cosmos as much as we should be concerned about the meaning we can gain from a proper engagement of what they wrote.

[1] Thomas Hopko, The Orthodox Faith. Volume 4: Spirituality (Yonkers, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1981; rev. ed. 2016), 110.

[2] Archbishop Joseph Raya, The Abundance of Love: The Incarnation and Byzantine Tradition (Combermere, ON: Madonna House Publications, 1989; 3rd ed.: 2016), 44.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.