Tristan Harris, a former Design Ethicist at Google who has been called the “closest thing Silicon Valley has to a conscience,” recently launched the Center for Human Technology to promote humane over addictive design. Harris is a leading critic of how digital devices and platforms are designed to capture and commodify our attention.

The “attention crisis” to which Harris and others are drawing our attention exists because we have become aggressively pursued objects in a frenetic attention economy. In spite of significant asymmetries of agency between us and the corporations that have turned us into their products, we must become more aware of how we participate and act within an information environment that competes for the limited and valuable resource of our attention.

Howard Rheingold identifies attention as the most important digital literacy or discipline. In the first chapter of his book Net Smart, Rheingold presents a number of strategies for managing attention, including being mindful of intentions and emotions. David Levy, in his book Mindful Tech, offers similar strategies for “task focus” and “self-observation.” But Levy emphasizes that something more is at stake with our attentional agency: “When we are mindful, we choose to pay attention to what is explicitly important to us; being mindful begins to reveal our values in a way wandering lost through the digital landscape can never do.”

While there are various views about the nature of attention, there is consensus among philosophers, psychologists, and brain scientists that attention is “involved in the selective directedness of our mental lives,” which is necessary for prioritizing stimuli for perception, thought, and action. In our present age of information abundance and hyper connectivity, the role of attention—what it is, how we use it, and what it reveals about our values—is an especially critical concern.

This new attention on attention is good. Our cognitive capabilities are limited; as Adam Gazzaley and Larry D. Rosen argue, we have ancient brains in a high-tech world. If we are to survive and thrive in our information- and connection-rich world, we certainly need more reflective strategies to interrupt our reflexive responses to environmental stimuli. But we also need to reflect deeply on more fundamental limits to our humanity.

In Book XI of his Confessions, Augustine reflects on the temporal and embodied nature of human existence, which divides our attention between past memories, future expectations, and present experiences. The human self is temporally distended, persistently distracted in the present by the presence of the past and the future. To manage everything to which we are exposed, we must constantly shift and direct our attention to certain things and be distracted from everything else. For Augustine, perfect or pure attention would be receptive and comprehensive rather than selective and limited—something impossible for humans. Only God can pay attention to everything.

David Marno links Augustine’s view of receptive attention with Nicolas Malebranche. Malebranche was critical of early modern information management strategies, such as memorization and notetaking, and more interested in the role of attention, which he described as a natural form of prayer. Prayer seeks an encounter with God, and attention seeks an encounter with truth. Both are characterized by passivity as well as activity: we pray words and listen; we focus our thoughts and thoughts occur to us. We seek but we also wait upon God and truth. For Malebranche, attention acknowledges the limits of agency without abandoning it. Attention is exercised toward a receptive disposition of attentiveness, which opens one up to receive a gift of knowledge or even the grace of God.

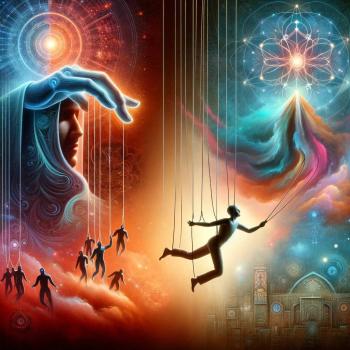

Simone Weil developed a comparable conception of attention that aimed to form a more proper relationship between modern technology and spirituality. Mechanistic technology was too reductionist, she argued, but attention opened one up to transcendence: when human faculties come up against a limit, one should wait at this threshold “in fixed, unwavering attention.” This involves waiting without seeking, but being “ready to receive in its naked truth the object that is to penetrate it.” As we suspend our own ends and empty ourselves, we open ourselves up to receive intellectual as well as spiritual revelation. On one level, such as in study, we may receive truth. On a higher level, called prayer, we may encounter God.

At the core of Jacques Ellul’s critique of technology was a concern about reality crowding out truth. Reality is about what can be seen and measured; truth is about human values and ends. More fundamentally, “Truth invites a posture of waiting and listening toward the other; reality invites an attitude of grasping at and holding power over these objects which seem so ready to be manipulated.” If attention is focused on and reduced to managing reality, we may close ourselves off from all that comes from truth.

As we navigate the information revolution and improve our selective attention to enhance our agency, we also need to cultivate a more receptive form of attention that recognizes the limits of our agency and is open to receiving something beyond us.