Significant digital divides characterize the digital age—divides related to access, literacy, and wisdom.

In the 1990s, as popular awareness of the social and economic potential of the internet grew, a number of advocates and policymakers became concerned about a social “digital divide” caused by inequitable access to networked information and communication technologies. Initially, the focus was on access to computers and connections (e.g., computers in schools and public libraries connected to the internet). While there has been progress in increasing access to networked devices, Bryan Alexander argues that access divides persist due to “wealth, education, race, age, geography, politics, and culture.”

In addition to access, there is another type of digital divide associated with skills or digital literacy. Digital literacy is a broad term used to encompass a range of competencies related to digital information, devices, and networks. In one sense, digital literacy refers to the effective use of information and computer technologies. But as a literacy, it also concerns the ability to “read” digital messages and media critically. At my university, we use the term to cover information technology literacy (working with devices, applications, and networks), information literacy (discovering, interpreting, evaluating, managing, synthesizing, and using information), participation (cultivating digital identity, collaboration, and learning networks), and creation (creating and sharing scholarly, professional, and other creative communications using various digital media).

Using technology effectively or well leads to considerations about using it ethically and wisely. Digital literacy programs should include reflective and ethical use, but ultimately these uses need to be rooted in deep values and formative practices. As I wrote in my previous post on “Attention, Reality, and Truth,” our values influence what we pay attention to actively as well as what we may be receptive to. Attention also functions to connect us with a larger narrative framework, which integrates past memories and future expectations with present actions. Without such a temporal framework, we are left with what Douglas Rushkoff calls “present shock”—a collapse of narrative into amnesia, apocalyptic fantasies, and aimless and unproductive weariness.

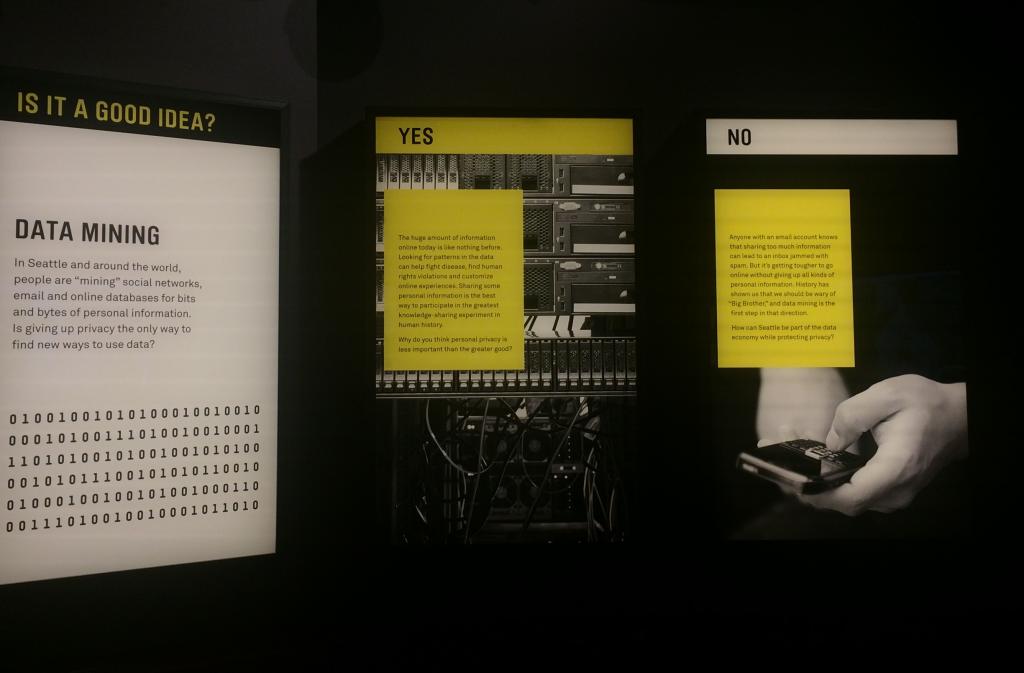

Consider the timely and increasingly important topic of digital privacy. Crossing the first digital divide involves creating a digital extension of oneself that must be managed. This is not a simple responsibility. The Federal Trade Commission just opened an investigation into the privacy practices of one of the world’s most popular social media platforms, Facebook, which lost control of personal data for some 50 million of its users. According to a recent poll, only 41% of US adults trust Facebook to “obey laws that protect your personal information” even though they use the platform regularly. A possible interpretation of this is: “People don’t trust Facebook with their private information, but they don’t care enough to change their behavior.”

Whether or not a digitally literate person decides to use Facebook, digital literacy should include the ability to interpret Facebook’s terms and policies, manipulate privacy settings, and intentionally curate a digital identity within and beyond the platform. A digitally literate person should understand how Facebook’s software limits one’s agency (through its technical design) and that the company may even compromise one’s agency (by losing control of its platform or not respecting its contract with its users). A digitally literate person should be prepared to manage and mitigate risks with any platform, and act in ways protective of one’s identity. A digitally wise person would ask more probing questions about such a powerful corporation and platform.

The most recent Facebook fumble concerns much more than one company’s responsibilities to its users. With Facebook, all of this has happened before and all of this will happen again. Julia Ticona and Chad Wellmon begin their 2015 essay “Uneasy in Digital Zion” with a discussion of a Facebook experiment that manipulated users’ news feeds to see if showing people more negative than positive posts would make them sad. It did, and the published results of the study made many mad.

Brett Frischmann argues that “fixing the Facebook problem requires a massive cultural shift”: “Nothing less than our humanity is at stake. We risk being engineered to behave like predictable and programmable people.” He concludes:

It’s too easy to blame companies that treat us as programmable objects through hyper-personalized technologies attuned to our personal histories, present behaviors and feelings and predicted futures. They bear some responsibility, but so do all of us.

More humane design and regulatory interventions will only go so far. The information revolution we are living through, and the new lives and world we are creating, require robust individual and cultural narratives about where we’ve been, where we want to go, and how we should get there. Without such narratives, we will realize another type of divide opening up within our information society—a divide between those with governing narratives and those who are governed by others’ narratives.

Transcending this digital divide requires narratives characterized by formative memories, intended futures, and transformative actions—such as a theological narrative informed by faith, hope, and love.