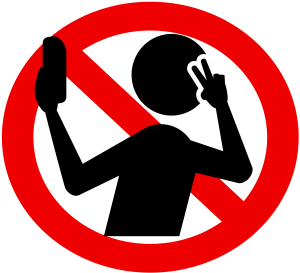

The Guardian’s Rana Dasgupta recently wrote a piece concerning the now common practice of posting of photos on social media. It’s title, suggesting that such an activity “is not living”, might give the impression of the all too familiar online rant about the seeming frivolousness of social media.

At one level, it is such a critique. Dasgupta draws our attention to the fact that by focusing on the digital record of an experience (of say a sight or food item) over the experience itself, we have missed the entire point of undergoing that experience and denigrated the activity and the experience thereof. It should be noted that this view is countered by Jacob Silverman’s Terms of Service, which suggests that the sharing with others of digital captures of experiences actually enhance those experiences, and even affirm the experience itself.

In spite of the differences however, one commonality binds these two views. It is a malaise that Dasgupta is alerting to. On the one hand, Dasgupta is reminding the reader that the digital technologies themselves manifest a devaluing of embodied experiences. “For more than a century”, Dasgupta says, we have been caught up in the machinic processes that have caused us to stop believing in our own experience, and – like a colonised people asserting themselves in the oppressor’s language – we feel a surge of dignity with each new word we learn of the machine’s own tongue”.

In a way, this captures in visceral terms the condition of what Jean Baudrillard in his Simulacra & Simulation called “hyperreality”, where simulated representations have become not only disconnected from the real world, but have acquired the power to shape the real world in its image.

On the other hand, however, this denigration of experience, in particular our memory, which comes with the urge to post photos of experiences online has a more sinister dimension. Dasgupta argues that in so obsessing over getting the picture right rather than receive the density of the embodied experience, we are also in a way preparing ourselves for death. Dasgupta brought the reader back to a pre-technocratic age, where the curation of photos were linked to another major social event: funerals.

Deep down, we have no real expectation that people really care about our photographic curations, that is until we die. Indeed, those who have lost friends with facebook accounts are probably familiar with the practice of trying to trawl through and retrieve photos of those who have passed from this life, before their accounts are deleted forever. Social media, Dasgupta warns us, only acquires the significance we seek from them at one point in our lives, and that is when our lives are over. By obsessing over our social media accounts, what we are ultimately doing is rehearsing our deaths while we still draw breath.