What is American cinema? Do we have a distinctive and original voice? For audiences around the world, they know us by our explosions, our effects, our superheroes. Nobody saves the world with quite as much chutzpah as Batman, Spider-Man, and the Avengers. But is there still room for independent filmmakers at the cineplex? Will audiences rally around alternative visions of freedom, equality, and justice? Beasts of the Southern Wild follows on the heels of previous Sundance Film Festival winners Winter’s Bone and Precious. These bracing stories celebrate remarkably resilient young women who navigate fractious families and grinding poverty. Hushpuppy is the newest super-heroine, further redefining cinematic girl power with her indefatigable spirit.

Greil Marcus embraced the ‘old, weird America’ where the rough edges of our democratic experiment linger. The Deep South raised up originals like William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and Johnny Cash. Beasts of the Southern Wild arises from that region rife with cinematic possibilities. Benh Zeitlin’s directorial debut revels in the distinctive sights and rhythms of the Louisiana bayou. Barnyard animals roam around the swampy denizens of the Bathtub, on the ‘wrong’ side of New Orleans’ levee. Fireworks fly, crabs are cracked and bourbon is downed by the bottle. This is where the real wild things roam.

Beasts of the Southern Wild takes us inside the trials and tribulations of six-year old, Hushpuppy (portrayed by the remarkable Quvenzhané Wallis). She puts her ear to the ducks, birds, and crayfish that surround her, listening to “the fabric of the universe.” She is wise beyond her years, tapped into how everything is connected. Hushpuppy is a natural born environmentalist, feeling each crack in the polar ice cap. Her mystical vision also includes aurochs, ancient wildebeasts that prey upon weakness. This precocious vision of wise youth deserves a place alongside Scout from To Kill a Mockingbird and the children from Night of the Hunter.

Hushpuppy has problems as deadly as the aurochs. Her mother swam away, leaving her mobile home behind. Hushpuppy lives beside Wink, who is a danger to himself and to his daughter. A bayou survivalist, Wink takes a whole chicken out of an ice chest, frying up it up for dinner. Dwight Henry makes a memorable screen debut as the unpredictable Wink. We wonder what beast might be next to be devoured. But those dangers pale in comparison to the storm brewing off the coastline.

The specter of Hurricane Katrina hovers over the Bathtub and Hushpuppy. We sense her vulnerability, alternately entranced and horrified by her situation. Yet, Wink and the Bathtub community are defiant in the face of the impending storm. He literally shouts at the elements, firing a shotgun into the sky. They resist the mandatory government evacuation. The Bathtub is made of people who never wanted to be found. They shall not be moved.

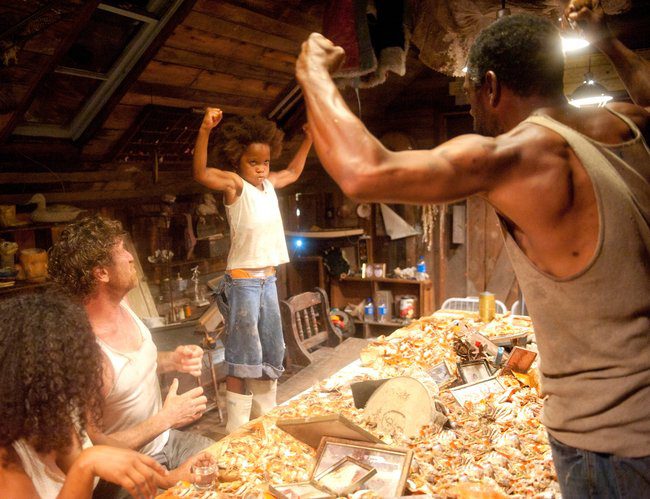

Self-sufficiency is an enduring American ideal. Wink may be suffering from a serious heart condition, but he repeatedly insists, “I got it under control.” Hushpuppy is told that she must learn how to survive, because someday it will be all on her. She displays her six-year old muscles with ferocious aplomb. Hushpuppy declares that “Even if daddy kills me, I ain’t gonna be forgotten.”

This roaring debut film from the Court 13 collective ensures that Hushpuppy will be remembered. It has already secured a place in American independent film lore at Sundance. Kudos to promising director, Benh Zeitlin, his co-screenwriter Lucy Alibar, and cinematographer Ben Richardson. But will Beasts of the Southern Wild find an audience?

In 2000, George Washington was an equally arresting film. Like Beasts, it follows mostly poor, African-American youth through an enchanted Southern milieu. A young, white, first time filmmaker cast complete unknowns that elevated the black experience to a magical level. The wide-eyed innocence of the child actors opens things up to charges of exploitation. Their every observation sounds like the poetic musings of a Terrence Malick film. Are these amateur performers reduced to magic negroes? Their voices may feel too prescient for mass appeal, but like George Washington, Beasts also contains some of the most haunting, beautiful, and memorable passages in American indie cinema. These are hard earned hopes. And yet, George Washington never found an audience until the Criterion Collection immortalized it in on DVD.

In wading into the social and political class struggle behind Hurricane Katrina, Beasts reopens one of the ugliest chapters of recent American history. Powerful documentaries like Trouble the Water and Spike Lee’s When the Levees Broke did not alter the material situation of their subjects. Beasts raises another warning bell through empathetic characters and a raucous celebration of life. It feels lived in, rather than preachy. It also reminds us of the disasterous BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill which ravaged the Gulf of Mexico on the same day principal photography began on Beasts. How does a region rebound from two devastating blows? Beasts pushes past the political, yanking us into the Bathtub’s desperate efforts to preserve an already precarious way of life. We understand why they resist efforts to be relocated, to get treatment. Hushpuppy fears what happens after we plug people into the wall. Zeitlin and company movie present a series of inconvenient truths that are seemingly answered with a crayfish boil. The lines between celebration and exploitation can get blurry. Yet it is so rare that we have a genre bending film that raises issues of representation and opens us up to reflection.

Beasts of the Southern Wild ultimately offers an alternative vision of race and class in America, circa 2012. In a melting pot, everyone blends together. The personalities populating the Bathtub are so distinct, that they will never melt. Some may not buy the rosy view of community presented in Beasts. It suggests we need to learn how to share space and resources, floating together before we all sink. But the picture rises beyond social critique by adding mystical qualities. The aurochs were created by dressing up real boars; placing them amidst the same kinds of digital backdrops that animate Hollywood’s biggest blockbusters. But these beasts feel timeless, the kinds of monsters that haunt the dreams of any and all six year olds.

Beasts of the Southern Wild deserves an audience as wide and diverse as American itself. It is a tasty gumbo—part coming of age, part community in crisis, part fable. And that is the American story still being writ, in small but significant ways.