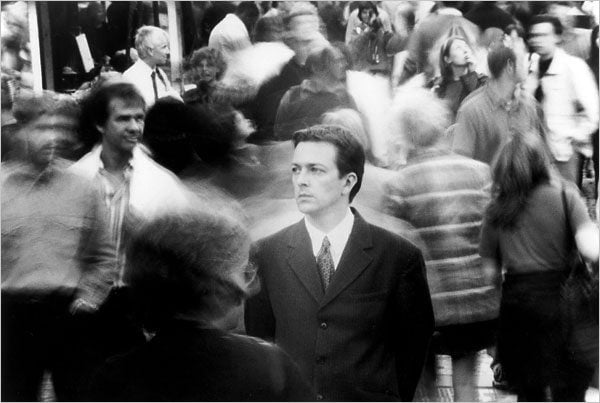

In anticipation of The Dark Knight rising in theaters this week, I am reviewing the remarkable films of Christopher Nolan. Only Quentin Tarantino comes close to creating such a high percentage of classic movies (according to the dedicated users of the Internet Movie Database). But while Tarantino revels in darkness, Nolan seriously laments our blind spots. So in my book, Into the Dark, I focused upon Nolan’s breakthrough film, Memento as a way into understanding his recurring examination of our divided hearts and minds. He mines the heart of darkness residing in even the noblest knights. Here is some of what I wrote in Into the Dark about his first three films, Following, Memento, and Insomnia (and before he made The Dark Knight, Inception, and The Dark Knight Rises). Do my initial thoughts still resonate?

British filmmaker Christopher Nolan’s smart narratives combat the myth of self-sufficiency. They are constructed like elaborate puzzles to suck in the most engaged, postmodern viewer. With three consecutive features ranked amongst the IMDb’s Top 250 of all time, Nolan has demonstrated a mastery of audience expectations, a mastery of movie magic. Thematically, Nolan takes on two holy tenets of Enlightenment thinking. One: all knowledge is attainable through a careful assembly of the facts. Two: I do not need anyone or anything beyond my autonomous self. In Christopher Nolan’s cinematic universe, misjudgments are not minor matters to be adjusted in the laboratory of life. Even our noblest obsessions can lead to murder.

In Memento, Leonard Shelby undoubtedly began his personal war with the best of intentions. But his amnesia got the best of him (or at least gave him a convenient excuse). Memento stands as an ongoing indictment of our collective amnesia, our need to place ourselves beside Leonard in the white suit (or hat). But what is the best way to remember death? Will retaliation satisfy even the most unjust murder? Leonard gets addicted to revenge. To satisfy his habit, Lenny needs stronger doses of both blood and selective memory loss. Falsehood feeds upon fresh fictions. We need hard truths to combat our love of lies. Who or what will reveal the sin and self-deception in our lives? Can a firm grasp of the facts undermine our convenient fictions?

To overcome the limits of our perception, we need frames of reference beyond ourselves. In his concluding speech, Lenny says, “I have to believe in a world outside my own mind. I have to believe actions still have meaning, even if I can’t remember them…We all need mirrors to remind ourselves who we are. I’m no different.” This is the all-important frame of reference we all need to remind ourselves of our place and purpose. So what kind of mirror are we looking at? Is it cracked? Distorted? If ours is broken, how do we get a new, more accurate mirror? Memento raises core questions of epistemology. It forces us to examine our receptors, our mirrors, lenses and recording devices—basically our entire mental capacity. How do we know what we know? What kind of information do we trust? Are there objective facts or only subjective experiences?

The issues explored in Memento turn out to be ongoing concerns of Christopher Nolan expressed throughout his artistic oeuvre. He has repeatedly returned to issues of self-deception, of transference, of trusting the wrong people—especially ourselves! Nolan’s first film, Following (1998) was shot on the cheap, as a weekend project in his native London. It begins with an ingenious premise: What if a voyeur becomes a victim of voyeurism? Following unfolds like a warm up for Memento, turning upon a film noir moll, “The Blonde,” who proves unreliable. Nolan’s fractured narrative also plays with time. And Following ends with a massive twist that forces audiences to rewind everything they’ve seen. Our ‘hero’ has allowed others to pull out the worst voyeuristic tendencies within him, with frightening results. This final revelation forces us to replay all we have thought and believed about the universe contained within Following.

Like Following and Memento, Insomnia (2002) suggests that evil resides within all people. It deals with secrets, with guilt, with confronting our demons. It includes the adage, “A good cop can’t sleep because part of the puzzle is missing. A bad cop can’t sleep because his conscience can’t let him.” Insomnia deals with painful memories. How do we process our regrets? Nolan told Electric Artists, “To me the film is about responses to guilt, and you’ve got two characters who deal with guilt in opposite ways, in fact that’s what makes the relationship between them quite interesting. I think on thematic level the film says something about the role of guilt in defining morality or suggesting morality. Both characters in some sense have transgressed to cause their reacting to guilt.” But rather than the shadowy world of film noir, Insomnia takes place in broad and unforgiving daylight. The dueling murderers in Insomnia will find no rest until their ugly secrets are revealed.

So what does Christopher Nolan reveal to audiences? Amidst an age of too much information, we must work hard than ever to see through media. I saw Memento at a pre-release screening. No reviews or expectations clouded my judgment. I was in the precarious position of not knowing what I was about to see. With no advance reviews to tell us what to what to think, we may come out cloudy in our vision. I wasn’t prepared to work so hard to get at a movie and its meaning. Memento tricked me because I relied upon pat notions of heroes and villains. Our assumptions about where truth resides can cloud our judgment. The church, the government, and Wall Street have all played upon our confidence and later been convicted of lying. When those designated as watchdogs, the Fourth Estate of journalism, resort to fabrication to spur their bottom lines, we have run out of institutions to trust.

In a world of spin, Memento challenges viewers to dig deeper, to look closer, and to become more active listeners. So, what if a manipulative cop like Teddy becomes the only person to tell Lenny (and the audience) the truth about Sammy Jenkus? Revelations can arrive in unexpected ways from unlikely sources. The biblical testimony from Isaiah, Ruth, or Habbukuk demonstrates how diverse God’s spokespeople can be. God’s story was communicated by a long tradition of eccentric outsiders, theology from the bottom up. Whether dealing with the arts or scripture, Jesus’ question remains, “Do we have ears to hear?” The truth is out there. But without developing eyes that see and ears that hear, even rich men like Bruce Wayne may end up as blind and self-deceived as poor Leonard Shelby.

Links to the complete Patheos conversation on The Dark Knight Rises here.