Can a motion picture be great even if it is thoroughly unpleasant? Do we need to like characters in order to love a movie? What about a film that nearly shuts out half the audience, dealing almost exclusively with male lust for sex and power? The Master mixes the sacred with the profane, delving into our ancient struggle to tame our drives, to master our base instincts. Joaquin Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman offer powerhouse performances exploring humanity’s bestial and spiritual sides (respectively). For director Paul Thomas Anderson, the spirit is mostly unwilling and the flesh is not weak. The Master is about men, desperate for love, but dogged by self-sabotage. Their choices are vexing. The Master is a demanding, impressionistic film that takes considerable time to process.

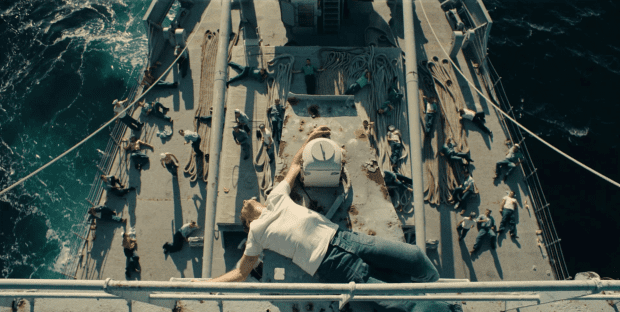

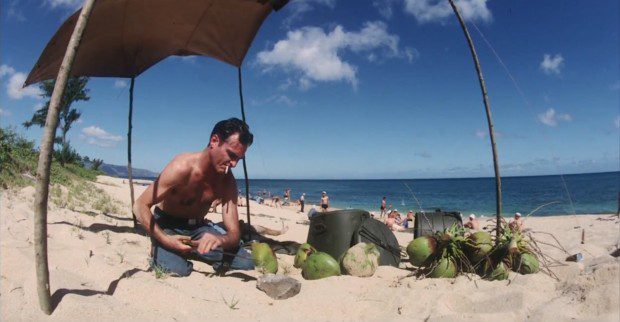

The Master is steeped in primal urges. It begins with an iconic image of a soldier at war. Fighting an unseen enemy. Fighting boredom. Drinking coconut milk. Making sculptures in the sand of a woman. The first words of dialogue deal with venereal disease. A scene of imagined intercourse is followed by actual masturbation. A tortured G.I., Freddie Quell, dissembles torpedos, draining their fuel for an alcoholic fix. Freddie lives like an animal. This is all in the first five minutes of The Master. No one can accuse writer and director Paul Thomas Anderson of holding back. He offers fair warning—The Master will be serving up strong stuff, guaranteed to make your skin crawl. (Note: this is decidedly not a date movie, in fact, it may be aimed only at men perpetually wrestling with their dual nature. Anderson, like Robert Altman before him, encourages full frontal portraits of women. It borders on the gratuitous, but then again, the subject is misplaced male projections).

The transition from combat to civilian life is rife with dramatic possibilities. Classic films like The Best Years of Our Lives delved into veterans’ awkward reentry. The Master employs dreamy songs from that earlier era. The costumes and settings are steeped in period details. But Radiohead’s ace guitarist, Jonny Greenwood also provides jarring, disconcerting chords that create an air of unease. As seaman Freddie Quell, Joaquin Phoenix, looks gaunt, haunted, and unstable. He places his hands on his slender hips in a way that suggests he’s holding his guts from spilling out. What the VA hospital may call a “nervous condition,” we now recognize as post-traumatic stress disorder. Even amidst the seemingly placid setting of a glamorous post-war department store, Freddie struggles to keep his anger under wraps. As the cool sounds of Irving Berlin’s “Get Thee Behind Me, Satan” waft on the soundtrack, Freddie seethes with contempt for the wealth and normality surrounding him. He is dogged by his demons. Normalcy drives him crazy. Can his scarred psyche be healed?

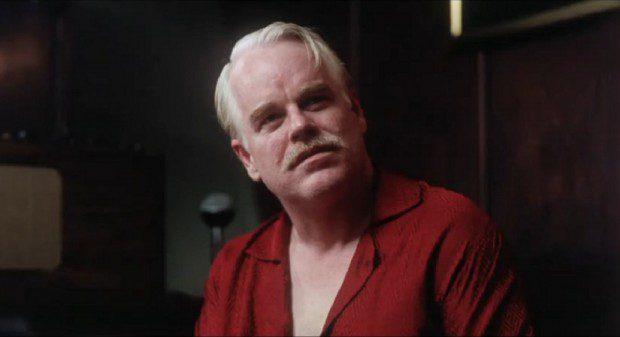

Stowing away on a luxury yacht, Freddie awakens amidst a community focused on plunging into our most painful memories. The Cause is lead by the charismatic author, Lancaster Dodd. His decadent red pajamas bleed across the screen into Freddie’s space. Dodd identifies Freddie as “aberrated,” chastising him for “wandering from the proper path.” Dodd identifies himself as a “theoretical philosopher” and a “hopelessly inquisitive man.” He allows Freddie to stay if he will continue to make more of his “remarkable potion.” Dodd sends him away with a final edict: “Scrub yourself, make yourself clean.” But how do we scrub away our most painful memories?

As Dodd, Philip Seymour Hoffman summons the electric megalomania of Orson Welles as Charles Foster Kane. Hoffman’s remarkable range as an actor can be traced in the gulf between his shy, gay teenager in Boogie Nights or his contentious nurse in Magnolia to the magnetic cult leader in The Master. Dodd considers Freddie the ultimate test of his principles, wrestling with a dragon. If he can tame a beast like Freddie, then surely The Cause can cure anyone.

Two scenes stand out as instant classics. When Dodd challenges Freddie to submit to “informal processing” (akin to auditing in Hubbard’s Dianetics), he burrows into the veterans’ past. He cuts through Freddie’s disengagement, awakening a determination to dig deeper. Dodd harangues Freddie, “No blinking.” The scene is shot in intense close ups. Paul Thomas Anderson has complete confidence in his actors’ ability to hold our attention. Secrets are spilled. A long lost love for Doris emerges. As Freddie’s greatest regrets surface, Anderson intercuts the interrogation with those poignant memories. The effect is mesmerizing. Dodd affirms him as “The bravest boy I’ve ever met.”

While Freddie struggles to keep his anger under control, financial improprieties hound Dodd and the Cause. Both men are arrested, tossed into side-by-side cells. Freddie goes berserk, chafing at incarceration. His self-destructive anger evokes Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull. Dodd sees all the progress made by his protégé slip away. He cannot turn jail time into a teachable moment. Anderson lets the two tour-de forces go in a volcanic face off. It is foul, funny, and frightening. Unfortunately, nothing that follows in the next hour matches this intensity. The further we get into the Cause, the more we, as viewers, want out.

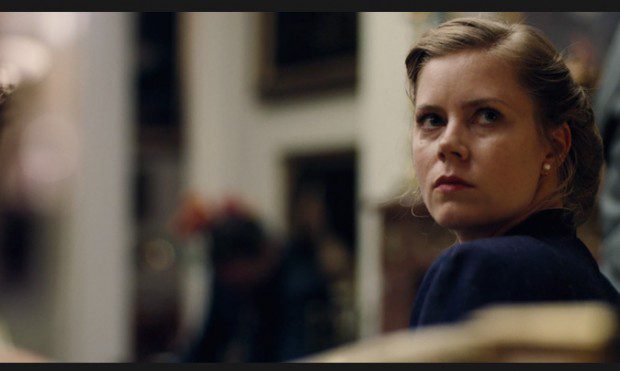

Paul Thomas Anderson doesn’t seem to care about the dogma animating The Cause. Dodd’s son, Val, suggests that “he’s just making it up as he goes.” Eventually, we understand the powerful woman behind the man. As Dodd’s pregnant second wife, Peggy, Amy Adams demonstrates an icy resolve, driving him to attack those who seek to discredit the movement. Her Lady MacBeth attempts to remove Freddie before he brings down the Cause. Peggy’s paranoia is a tie that binds the Cause together. But Dodd doesn’t want his prize project to go.

The Master does not tell us what to think about the Cause (or Scientology). Casual references to illnesses that started trillions of years ago hint at Dodd’s obsessions with time travel and extraterrestrials. Arrested in Philadelphia, Dodd questions “What code, what honor, what galaxy?” the police are inhabiting. When the Cause convenes in Phoenix, the camera catches odd glimmers of characters that look like aliens on the horizon. Slowly, they come into focus as humans. Dodd’s focus shifts as well, from the past to the future, from “Can you recall?” to “Can you imagine?” But Dodd’s patience towards his critics and challengers has grown even thinner. He has become far more like Freddie, with a hair trigger that could snap at any time. Dodd’s flesh is slowly overruling his mind.

One of the earliest, core controversies in Christianity wrestled with the bodily nature of Jesus. Docetists could not imagine that God would ever appear in flesh. Some taught that Jesus’ spirit inhabited a body. Others thought Jesus’ appearance was not physical but phantasm. Orthodox creeds formed at Nicea affirmed Jesus as fully God and fully man, spirit and flesh. The Cause taught Freddie that we are spirits, only borrowing our current bodies in a trillion year journey. Dodd and his followers are rapt by an old fallacy, that the body is just a vessel dragging down our true spiritual nature. While the Cause seeks to transcend this earthly plane, Freddie continues to cling to the bodily urges (for sex and drinks) that drive him. So who will win their battle? The Master suggests we cannot separate mind and body, the spirit from the flesh.

(Warning: spoilers ahead!)

The vast expanse of the desert suggests freedom. Dodd challenges Freddie to pick a point on the horizon. The open space echoes the lure of the sea, a recurring visual symbol throughout the movie. Freddie cannot stand to be confined. While the Cause keeps Freddie trapped between walls, skulking like a caged monkey, a Norton motorcycle provides a means of escape. The scene taps into classic images of American masculinity, especially Marlon Brando in The Wild Ones. Freedom looks like a guy in jeans, cruising at top speed, through the American west, towards a destination unknown. Has the student learned all that the Master has to offer? Offscreen, a beloved ‘son’ leaves a proud father behind.

In all of Paul Thomas Anderson’s work, the tension between fathers and sons is paramount. Consider father figures like Sidney in Hard Eight. Or how Jack Horner presides over his stable of porn stars like Dirk Diggler in Boogie Nights. In Magnolia, the pain between ailing game show producer Earl Partridge and his estranged son Frank T. J. Mackey is palpable. There Will Be Blood can also be read as a cautionary father/son story where H.W. is literally rendered mute before his overpowering Dad, Daniel Plainview. In The Master, Freddie is far removed from his immediate family. Sexual abuse plays a central role in his own fractured relationships with the opposite sex. The normalcy embodied by Doris becomes a siren call that he fails to answer. Cut off from Mom, from Dad, from the love of a women, Freddie falls in with the most wholesome family he can find, The Cause. Lancaster Dodd presides over a strange brood, full of secrets, bonded by a persecution complex. Freddie serves the enforcer for the Cause, the “man” that Dodd’s own son, Val, seemingly refuses to be.

The Master is elusive and enigmatic right through the ending. There Will Be Blood gave us a memorable milkshake. Greed unraveled the oilman and murdered the preacher. The Master offers Freddie a threatening ultimatum, “If you leave here, I don’t ever want to see you again. You will be my sworn enemy in the next life. I will show you no mercy.” But then Dodd breaks into an unexpected song, “Slow Boat to China.” The phrase was originally rooted in poker playing; hoping a player will stick around so they could be fully exploited. Such menace may reside in Dodd’s choice. But the song by Frank Loesser turned into a romantic wish. And genuine affection does seem to undergird the dance that Dodd and Freddie have been engaged in throughout The Master. Dodd has been a generous father figure, nurturing Freddie back to life. Their relationship is physical and spiritual, fused together in powerful ways.

Freddie has gotten better. He manages to call upon the home of his first true love, Doris. He receives the news that Doris has gotten married and had children without going ballistic. This is genuine progress. Perhaps rooted in the teaching of the Cause, but also tied to the passage of time. Almost a decade after World War II, Freddie appears ready to move on.

Dodd questions Freddie’s drive for independence, “If you figure out a way to live without serving a master, than you’ll be the first person in the world.” (Echoes of Bob Dylan’s famous song, “Gotta Serve Somebody,” echoed through my head.) Freddie has been mastered by booze for far too long. Under the Cause, Freddie becomes a better man. But he no longer wants to answer to Dodd. Freddie returns to the comfort he sought while serving in the Pacific: the physical love of a woman. Clearly, Freddie learned a few psychic techniques from the Master. Processing becomes playful patter, bedroom talk, directed at the woman he seduced, Winn Manchester. He calls her, “The bravest girl I’ve ever known.” My colleague at Patheos, Jeffrey Overstreet explored the nuances of the scene and the potential ties to Winn’s name. Their interaction feels like a goof, a lark, just a roll in the sack. It is one of the few, genuinely joyous moments in the movie. Love and laughter serve as a healing balm. The Master concludes with Freddie’s mind wandering back to the beach, beside a woman made of sand. Is he finally at peace? Or will he only be satisfied with fantasies? While the Master crafted an elaborate “science” to free our spirits from our bodies, Freddie’s soul will only find rest in a paean to earthly love.

The arduous film finishes with Patti Page singing, “Changing Partners.”

We were waltzing together to a dreamy melody

When they called out, “Change partners” and you waltzed away from me

Now my arms feel so empty as I gaze around the floor

And I’ll keep on changing partners till I hold you once more.

Though we danced for one moment and too soon we had to part

In that wonderful moment something happened to my heart

So I’ll keep changing partners till you’re in my arms and then

Oh, my darlin’ I will never change partners again

Freddie has danced with alcohol. He has danced with Dodd. All he really wanted was to dance with Doris. Will his heart always reside with her? Or will he find a new permanent partner, someone with whom he can conclude, “I will never change partners again.” Maybe we all have to serve somebody. But The Master demonstrates how desperately, we never want to dance alone.