I’m disappointed by the dismal box office returns for Cloud Atlas because it is serious fun. Those two concepts, “serious” and “fun,” are rarely melded together in movies. Juggling those disparate tones is particularly tricky when you have six stories in play. The effort to adapt David Mitchell’s 2004 novel, Cloud Atlas, to the big screen may have been doomed to failure (or at least, misunderstanding) from the beginning. Yet, I found it both engaging and entertaining, highly deserving of a broad, enthusiastic audience.

The scope and structure of a complex book like Cloud Atlas left it labeled as “unfilmable.” In taking readers from South Seas slave ships through composing a British symphony, from nuclear reactors in seventies San Francisco to a post-apocalyptic Hawaii, Mitchell wound readers up in a chronology that runs from the past to the future before reversing the feat. A cinematic version was bound to leave plenty of viewers confused. But the ambitious trio of filmmakers, Andy Wachowski and Lana Wachowski (of The Matrix fame) and Tom Tykwer (of Run Lola Run renown) dare to intercut across centuries and continents to bring Cloud Atlas to the big screen. They make a simple request, “If you, dear reader can extend your patience for just a minute, you’ll see there’s a method to our tale of madness.” Unfortunately, their faith was not rewarded.

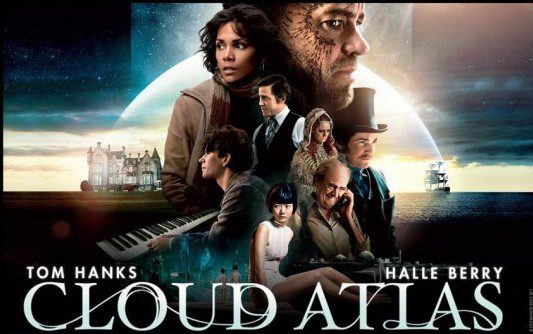

The sight of stars like Tom Hanks, Halle Berry, Hugh Grant, and Susan Sarandon in several roles (and under layers of makeup) may strike some as a gimmick. Yet, the recurrence of the same cast in different eras reinforces the central thesis of the story: “From womb to tomb, we are bound to others, past and present.” Given the ominous tone in previous films by the Wachowskis and Tykwer, I entered Cloud Atlas with a fair amount of trepidation. While the trailer looked amazing, I feared that the story would bog down under the temptation to make a “big statement.” The Matrix grew more ponderous and portentous with each sequel.

Subjects like the abolition of slavery, environmental disaster, and the future of humanity are heavy. Power brokers throughout the episodes in Cloud Atlas suggest, “The weak are meat and only the strong do eat.” But the playful performances, especially from Tom Hanks, Jim Broadbent and Hugo Weaving, lighten the proceedings considerably. They are clearly having a good time, relishing the opportunity to play multiple roles and try on odd hairpieces, costumes, and teeth. The filmmakers also seem to relish the chance to explore different cinematic genres, from swashbuckling adventures to a 70’s corporate espionage thriller like The China Syndrome.

The most enthralling sequence is set in New Seoul circa 2144. An otherwise ordinary clone, Sonmi-451, becomes a symbol of revolution (note the conscious hat tip to Ray Bradbury’s seminal sci-fi story, Fahrenheit 451). Korean actress Doona Bae turns the role of fabricant into the most compelling character in Cloud Atlas. The seeds of rebellion are planted in Sonmi’s psyche when a fellow servant at Papa Song’s diner insists she “will not be subject to criminal abuse.” The resistant are dispatched in a particularly bloody way. Sonmi seeks an opportunity to flee a world where she’s been taught to “Honor Thy Consumer.” The promise of “exultation,” an enforced retirement that arrives after 12 years of service, rings hollow to Sonmi.

Flying motorcycle chases through the glittering streets of New Seoul echo the high tech future in The Matrix. Sex between fabricant and ‘pure blood’ human is celebrated as sacramental. Sonmi takes on the messianic role that was also conferred upon Neo. Filmgoers seeking religious symbolism will find an abundance of imagery to parse.

Cloud Atlas blurs the lines between those who appear to be other. The shape shifting roles which have Hugo Weaving playing brutish female nurse or Halle Berry operating as a Chinese male doctor echo director Lana Wachowski’s own real life transition from male to female. The filmmakers challenge us to see how much we have in common despite categories of race or gender or age which potentially separate us. Despite slave traders’ efforts to treat Africans as savages, the arrival of mulatto offspring begins to break down racial lines. By the time we get to the future, we’re all a little bit Asian. In Neo Seoul, machines are outraged by people’s inhumanity. The film gives us a Cloud’s eye view of progress and tolerance across time. It challenges our tribalism today (and tomorrow).

Unfortunately, the future comes across as a bit dim. The most distracting segment of the movie places Tom Hanks as simplistic survivor, Zachry, in a verdant, post-apocalyptic island. Hanks and Halle Berry exchange a pidgin English that plays like something out of the antebellum South; it feels awkward and stilted. Hanks’ tribe engages in a superstitious faith fueled mostly by fear. It is not clear why the green devil Georgie that torments Hanks speaks in clear, contemporary English (maybe because that’s now an ancient language?). But the future looks primitive, like The Hunger Games gone wilder. As the narrative shifts amongst the six storylines, you want to linger with some characters like the articulate Sonma and avoid others like the mumble-mouthed Zachry. I appreciate the ambition inherent in the material. Yet, the film does drag, perhaps coming in twenty minutes too long. It comes across as an important idea that fails to keep us emotionally involved.

These criticisms should not keep viewers away. I love how Cloud Atlas blends genres in an effort to erase boundaries. It is a generous love song to humanity. It demonstrates how religions arise. Speeches delivered by Sonmi under duress become a prophetic comfort centuries later. Yet, this doesn’t mock religion, but expresses how we learn from and inspire each other over time. It could be read as a Buddhist track rooted in reincarnation or as a celebration of cultural influence. (Alyssa Rosenberg aptly summarized Cloud Atlas as “a deeply religious movie in search of a theology.”) It is a paean to freedom and endurance. We don’t know how influential an underappreciated concerto or a comic biography might become in the future. But we are all challenged to make the bravest ethical choices within our times and context.

Resisting the devil takes many forms, from protecting a copyright to blowing the whistle on nuclear shortcuts. The forces that slash and burn will always be with us. How will we respond? But allowing them to divide us or by engaging in active resistance? We cannot anticipate all the challenges ahead, but we can draw strength from the courage needed to oppose slavery or escape from a retirement home.

This is the basic wisdom that has been shared around campfires for millennia. It transcends space and time. It cuts through cynicism. Have we become so fragmented as filmgoers that we inherently reject a film that attempts to bring film history, genres, and people together? Perhaps audiences couldn’t embrace a story about unity during the most contentious and divisive presidential election in our collective memory. This is an expansive vision arriving at a reductionist time. It takes the long view, challenging us to rise above divisions of race, gender, and species. Over time, we may come to appreciate the generous spirit that informs this ambitious omnibus. Or this independently financed epic may represent the last gasp of the innovative class of ’99 (Wachowskis, Tykwer, P.T. Anderson, Spike Jonze, Night Shyamalan, Kimberly Pierce, David Fincher, Alexander Payne) in their failed effort to forge a cinematic future.