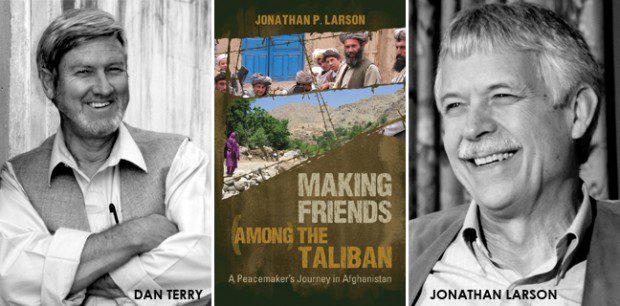

Veteran’s Day is an important time to pause, remember, and honor our fallen soldiers. We are all the beneficiaries of their blood, shed on battlefields far and wide. But what about those who fought for peace without the use of guns or ammo? How do we honor fallen peacemakers? Jonathan P. Larson celebrates the legacy of his lifelong friend, Dan Terry, in Making Friends Among the Taliban: A Peacemaker’s Journey in Afghanistan and in the companion documentary, Weaving Life. (Free copies of the book and the DVD available to two of the best responses to this article below).

The title alone is so strange and unsettling, Making Friends Among the Taliban. It might as well read, “Why I love the Ku Klux Klan.” But then, a Civil Rights advocate like the Reverend Will Campbell already demonstrated that if we claim to be serious about loving our enemies and praying for those who persecute us, then that must include people like Klansmen. Who now provokes more fear and contempt than the Klan? Shooting brave girls like Malala Yousafzai shot in Pakistan has brought almost universal disgust toward the Taliban.

Jonathan Larson celebrates how Dan Terry “lived his life generously and joyfully in Afghanistan during a period when famine, coups, revolution, war and displacement shook society to its foundations….Dan was a good man in bad times.” While acknowledging the brutality that shot down Terry and nine more relief workers in cold blood, Making Friends Among the Taliban challenges us all to combat violence and aggression with love.

Dan Terry grew up in the foothills of the Himalayas, borne to parents who served as missionaries to India. Dan and the author, Jonathan Larson, were classmates at the Woodstock School in India, where they encountered the young Dalai Lama in 1960. After graduating from college in the States, Dan’s sense of adventure lured him back to the Himalayan region. While serving at a clinic for the Hazara people in central Afghanistan, Dan met Seija, a Finnish Lutheran nurse, who became his wife. Dan and Seija raised three daughters while working with the International Assistance Mission. During the Soviet occupation in the 1980s, Dan and Seija ferried the wounded to makeshift hospitals across Kabul.

When Dan was held captive by warlords, he considered it an opportunity to develop a new friendship. As Larson recalls, “He believed there was no reason to regard the menace of a captor as anything but friendship in disguise.” Dan Terry welcomed the chance to have tea with Taliban commanders. His extensive knowledge of Afghan customs and struggles would result in the Taliban releasing Dan (against orders). What we might consider foolish or naive, Dan embraced, declaring “Hostage-taking is just another form of hospitality.” He truly earned the nickname, Pagal, a.k.a. “Crazy.”

Yet such craziness also saved countless lives, especially amongst the remote Hazara people. When they were cut from supplies in a particularly brutal winter of 1999, Dan persevered, finding a way to get food past the Taliban to the starving Hazara. Dan was a perpetual tinkerer, keeping Jeeps, Land Rovers and trucks going amidst rocky roads and trying conditions. He rallied locals (what he called ‘enfranchising others’) to break up the ice long enough to get life saving supplies to the Hazara people along what came to be known as the ‘Dantri,’ (as in Dan Terry) road. Dan’s ability to navigate mountain passes and talk his way through roadblocks resulted in essential relief.

Dan and Seija were troubled by the primitive health care found in remote Afghan villages. How to get crucial education to women about childbirth and infant care? Dan attended countless Afghan shuras, gatherings of local (male) religious leaders. Slowly, they warmed up to the idea of women gathering for an exchange of information, where grandmothers could impart their knowledge of birth and childrearing. The Afghan government now mandates that young women and mothers exchange stories and share collective wisdom.

Despite local victories, the peacemaking work of Dan and Seija was continually challenged by geo-politics. Dan observed, “The first rule of thumb in nearly every situation here is to acknowledge conflict.” Dan’s commitment to interfaith understanding led many to describe this Christian missionary as “More Muslim than we are Muslims.” He practiced humility, was generous to widows and orphans, and constantly strove for justice and peace. In an increasingly armed and bloody conflict, Dan remained defenseless, modeling the Afghan proverb that “an unarmed person can be more dangerous than an armed one.”

It was tough to proclaim peace amidst airstrikes. As Dr. Lisa Schirch asserts in the book, “The peace that Afghanistan needs will not be delivered by helicopter.” Military campaigns to win over “the hearts and minds” of invaded peoples cast suspicion on the efforts of peacemakers and relief workers. Dan negotiated the return of a downed American drone so as to avoid further bloodshed. Yet, the slaughter of 16 Afghan civilians in the Kandahar region by United States’ Staff Sergeant Robert Bales undercuts efforts to broker a fragile peace.

The book concludes with Dan’s final mission, leading a team of nine medical aid volunteers into the remote hills of Badakhshan province. The mountain villages were only reachable on foot. Despite his reputation as a humanitarian aid worker, Dan and his colleagues were stopped and executed. Speculation of robbery was undermined by how many possessions were found amidst their bloodied bodies. Local Taliban leaders who respected Dan’s relief work took no credit for the murders. Dan’s warm relationship with Afghans suggests that Pakistani insurgents may have been responsible.

While we would cry out for justice, Dan’s family did not want to turn the deaths into an international incident. They did not demand retribution. They even declined posthumous awards for Dan, sensing that heroic honors may undermine Dan’s lifelong work amongst the Afghan people. Perhaps they took solace in Jesus’ assertion that “Blessed are the peacemakers.” The epitaph on Dan’s grave reads, “Above all, clothe yourselves in love.”

Making Friends Among the Taliban befuddled, confounded, and challenged me. How do we turn our conviction into actions? We may not all be called to befriend warlords, but we can all turn the other cheek. When tensions escalate, do we have the disposition to diffuse it with a well-timed word, a knowledge of local customs, a deep understanding of the other? We can bemoan the tribalism that continues to bewitch Afghanistan, but we must also work on the ties that threaten to unravel our relationships with friends, with family, with our fellow Americans. We must all be diligent to wage peace.

(We’ll send the book and DVD to the two best examples of peacemaking posted below. Tell me what kind of peace and reconciliation work you’ve seen in your neighborhoods and communities.)