We don’t spend much time thinking about the nature of photography. What is it we are trying to capture in a single frame? How does the presence of the camera on our smart phones potentially undermine a beautiful moment? I’ve often found myself so caught up in trying to document one of my children’s events (a school play, a music performance, a championship game) that I miss the experience itself. How might we approach photography to enhance our sense of presence rather than as a barrier or destruction? With the cameras embedded our phones, we capture so many snapshots of our lives. Facebook and Instagram make it easier to post our pictures for friends and family. The instantaneous nature of social media is so remarkable, our joy and laughter can be spread from wherever we are. Snapchat has turned photography into a new form of texting, making our cell phone photos vanish within seconds. Photography is more ubiquitous and impermanent than ever.

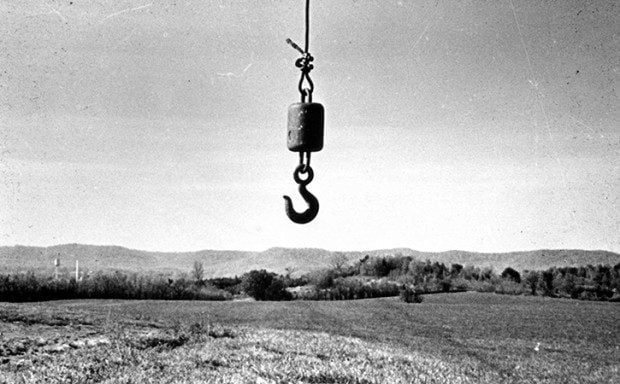

In Eyes of the Heart, Christine Valters Paintner explores “photography as a Christian contemplative practice.” She approaches photography as both an art and a spiritual discipline, demonstrating how combining both practices can deepen us. She hopes the camera will become a tool for “deeper vision, supporting and enlivening contemplative seeing.” Christine Valters Paintner’s remarkable resource is featured in this month’s Patheos book club. Thanks to Eyes of the Heart, I learned that Thomas Merton viewed photography as an extension of his spiritual disciplines like this evocative image, “The Sky Hook”, provocatively labeled as “the only known picture of God.”

Expanding upon her doctoral work in Christian spirituality and as online abbess for Abbey of the Arts, Paintner points out how the language we bring to photography reflects skewed values. In “taking” or “shooting” pictures, we create an odd distance between our selves and the eternal moments around us. Shouldn’t we adopt an attitude of receiving a photograph as a gift? While we still polish our technical skills in preparation, when the moment arrives, we are receiving something strange, wonderful, perplexing or beautiful. To recognize it, to truly see what is happening, we must pause, focus, and frame, all key components of contemplative prayer. We may want to “capture” a moment, but aren’t we better allowing the moment to capture us?

Christine Valters Paintner challenges us to slow down, to adopt a more sacred approach to life. Eyes of the Heart is a thin book of thick ideas, meant to be savored rather than consumed. We are invited to work through each chapter at a measured pace. She includes practical photography assignments to graft contemplation into our daily routines. Or perhaps more appropriately, she challenges us to allow contemplation to break or enliven our routines. For it is by studying the everyday objects and people we encounter that we get beyond the surface and the mundane.

Her first assignment centers on a single object. We are invited to photograph 50 images in fifteen minutes of something we see every day. What a great way to study the light, the shadows, the angles. We put something in context, going for wide shots, for close ups, searching for subtle differences. And then, we are challenged by the author to take just one image for the next five days. What moment, when the light is just right, should we focus upon? Eyes of the Heart awakens us to find the sacred amidst the (seemingly) mundane. Paintner includes brilliant quotations throughout each chapter to sharpen our senses like Marcel Proust’s observation that “The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.” She also includes her own photographs that emerged from contemplative walks and conscious reflections.

Each chapter focuses upon different aspects of the photographic process. Concentrating upon black and white photography brings shadows and light to the fore. Paintner encourages us to stare into the shadows, to consider what might be revealed in the darker corners of our photographs (and lives). When we carefully consider the frames and borders we place on our photos, we start to think about positive and negative spaces in our lives. Do we feel cramped and crowded? Do we need more room to breathe? Paintner also devotes an entire chapter to color, making connections between the symbolic use of color across art history and the church calendar. How do the colors we are drawn to reflect a particular spiritual longing or orientation? Paintner encourages us to see our photographs as a mirror, reflecting back our deepest concerns and desires. Studying our photographs is an important way of gaining perspective, where have we been as a way to determine where are we. In an unreflective age of Instagrams, I found myself agreeing with Dorothea Lange’s quotation, “In a sense your photographs are your autobiography.” We must study our Facebook Timelines in order to see the patterns, discern our concerns, reframe our perspective with eyes of the heart.

We also must be more thoughtful about how we receive photographs. We are surrounded by so many images that it is easy to lose perspective. We race to appointments, we fast forward through movies, we watch an entire season of a television series in one blurry-eyed weekend. Christine Valters Paintner offers us a vital alternative. Her visio divina is designed so that we might see the Divine. We can continue to take mere photographs or we can begin to see the camera as an invitation to holy contemplation, a sacred approach to life. As a film professor, I found Eyes of the Heart to be life-giving, essential reading for all aspiring filmmakers and visual storytellers.