Pascal by day, but Melville by night. No wonder I can’t get a New Year’s letter out the door.

Pascal by day, but Melville by night. No wonder I can’t get a New Year’s letter out the door.

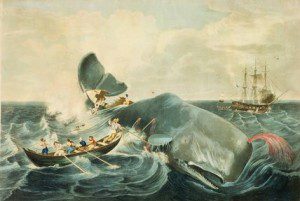

Last night I finished Moby-Dick, an enterprise I started, once, long ago, and found too mind-numbing even for me. My daughter, an English Lit major, warned me. “Read only if assigned. Then you can write a paper on it and get credit.” Unfortunately, it’s part of a Franklin books collection my parents gave me as a graduation gift from high school, and thus an unspoken mandate of sorts. And Moby-Dick has taunted me, all these many years, with my rebuff; I, in spurning it, had been conquered by it; the White Whale’s flukes slapped me silly. So I picked it up again (little knowing that my determination to succeed was, itself, Ahab-ian.)

But now? Done. Thinking more than once, “Die, stupid whale, die, so I can get on with something that tells me nothing about the dimensions of whale skeletons or the ambergris that comes from whale guts,” I come to end. And Moby-Dick survives. And I, with Ishmael, watch my weeks of reading circle the sucking vortex of the sinking Pequod.

Worth reading? Yes, I suppose so: for vanity’s sake; for the really transformational knowledge I’ve gleaned about whales; for the reassurance that my desire never to “go to sea” has some basis in reality.

But two take-aways, reminders for those of you who read the book, and spiritual “cheat sheets” for those who haven’t/won’t:

1) Ishmael. The book’s most famous line is its first: “Call me Ishmael.” And, then, a few chapters into the novel, Ishmael pretty much disappears from view, though the entire narrative is his. And there he is in the end, the sole survivor. (Sorry if these comments are spoilers. You’ve had plenty of time to read it yourself.)

Ishmael looks like the center; in his own mind, he is the center, obviously, as the observer; and yet very little of the book, almost none of it, is about Ishmael.

I, too, am Ishmael. I am the observer, the world around me the observed; I begin my story, and there I will be at the end of my story. But very little of my story is really about me. I’m in the boat; I overhear the conversations. The heat of the great vats liquefying the whale blubber into oil sears my face; the long hours in the crow’s nest, watching an unchanging horizon in the face of a relentless sun, weary me. I am a part of the story, a narrator of the story, but not the center of the story.

2) Ahab. The crazed captain of the Pequod is obsessed. Yes, he wants revenge for the great injuries the monstrous white whale had inflicted on the last hunt. Every stumpy step the captain takes on his ivory-crafted leg calls him to retribution. And yet, of course, his mania is irrational. As Starbuck, his first mate, declares early in the novel, revenge is for intentional harm and Moby-Dick is not an intentional creature.

In truth, though, it is not revenge that drives Ahab, but that “je ne sais quoi” that compels each of us to behave in destructive ways, even when we know, know, that these choices lead to death.

Ahab: “What is it, what nameless, inscrutable, unearthly thing is it; what cozening, hidden lord and master, and cruel, remorseless emperor commands me; that against all natural lovings and longings, I so keep pushing, and crowding, and jamming myself on all the time; recklessly making me ready to do what in my own proper, natural heart, I durst not so much as dare?”

I’m neither a captain nor a novelist, but this, this I understand all too well.

Paul: “For I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. Now if I do what I do not want, I agree with the law, that it is good. So now it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells within me. For I know that nothing good dwells in me, that is, in my flesh. For I have the desire to do what is right, but not the ability to carry it out. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I keep on doing.” (Rom. 7)

Mulhern: “I imagine good, I pray for good, I hope for good, but when I come to stretch out my hand, I take what is less good, no good, ungood. What is this fatal weakness that cannot conjure into reality what I choose in my heart?”

Choose life! (Dt. 30)

And so, the weird thing is that Ishmael, beginning and ending the book but so seemingly inconsequential throughout the story, is the character I cling to, like the bobbing coffin-lifebuoy that saves Ishmael’s life. He chooses life. In fact, his very desire to serve on a whaling boat, described at the beginning of the novel, is a desire to escape the emptiness of his life and enter into vitality. “I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way I have of driving off the spleen… Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet … I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can…. I am in the habit of going to sea whenever I begin to grow hazy about the eyes…” And one odd glimpse, midway through the book, relates Ishmael’s post-Pequod experiences—“smoking upon the thick-gilt tiled piazza of the Golden Inn in Lima.”

And yet, he is a no one—the main character and a no one. There’s some comfort in that. That, and the fact that my Franklin edition of the novel contains sixteen lovely colored lithographs.