In pursuing Pascal, it is not long before we come face-to-face with a conundrum. It’s the sticky wicket that challenged Pascal, and while we won’t be able to resolve it, we can at least look at it.

In pursuing Pascal, it is not long before we come face-to-face with a conundrum. It’s the sticky wicket that challenged Pascal, and while we won’t be able to resolve it, we can at least look at it.

Last week we talked about the violent division in French society between Catholics and Protestants. Religious conflict wasn’t exclusively French of course; the Germans had their Schmalkaldic War between Lutherans and Catholics; the English had their years of seesaw oppression—from Catholic to Protestant back to Catholic back to Protestant, chased by a messy civil war between Puritans and Anglicans; the central European communities had their Thirty Years War; the Spanish had their Inquisitional terrors. Equal opportunity carnage. It was the horror of religious violence that, in part, triggered the skepticism and virulent rejection of all faith that fed the Enlightenment.

In France, however, we have a peculiar nuance in the antagonism between Catholics and Protestants—the existence of a rather unusual sect that, in some ways, stood in a no-man’s-land between the two combatants. These Christians were avowedly Catholic, and rejected utterly the Protestant option. But the Catholics did not seem to want them, and would happily have thrown them on the Protestant pyre.

This small sect of Christians believed themselves to be part of a movement to recover and restore the heart of Catholic faith and practice; they perceived themselves to be, in fact, a Catholic reform movement. They, like so many who chose the Protestant option, were disheartened and appalled at lax Catholic morality, the lack of genuine spiritual life, the callous disregard for sacramental realities, the casuistry and power-passion of religious authority. But no way did they want to separate from the Church—they wanted to restore it, revive it. (They aspired, however, to do a better job than Martin Luther had.) And their inspiration was the work of a Belgian Catholic bishop, Cornelius Jansen, who had written a lengthy book, published in 1640, called Augustinus. I imagine you can guess the topic of the book. Those who stood under the banner of this book were called Jansenists. And the Jansenists got into a lot of trouble.

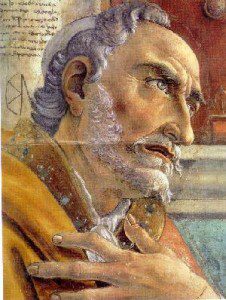

Now, if I tell you that Jansen felt that Augustine—the fifth-century Church Father, the great author of Confessions and City of God, the acclaimed founder of western spirituality—was in fact the voice most needed in the Church of the day, the voice of renewal and reformation that Catholic Christianity needed to recover, you might wonder how that could possibly get Jansen into trouble. After all, this is Augustine we’re talking about. It’s not like Jansen was promoting, oh, I don’t know, say Confucius as the solution to the problem.

Nevertheless, Jansen took Augustine’s teaching about grace, about sin, about human nature, and used it to point out the ways that the Catholic Church had failed to teach people the truth. Augustine had strong words about human depravity and the need for grace, a grace that was dispensed not nilly-willy (as the Church seemed to do), but according to the severe mercy of God and received through the deep contrition (342 pages of Confessions anyone?) of the stricken soul. Jansen essentially accused the Catholic Church of abandoning Augustine. (This did not sit well with Catholic authorities, and ultimately Jansenism was condemned by a papal bull, Unigenitus, in 1713.)

Specifically, Jansenism attacked the Great Catholic Reform Movement of the post-Reformation years: the Jesuits. Now this is a problem. The Jesuits were “the Pope’s men,” the vanguard of Catholic advancement, with one overriding purpose: to advocate papal power, authority, and teaching. In other words, you don’t take on Catholic reform by attacking the pope’s reform warriors.

Active on nearly every continent and involved at every level of government and influence, the Jesuits had acquired so much power by the 17th century that the head of the Society was given the nickname “the Black Pope,” contrasting the black robes worn by the Jesuits to the white robe worn by the pope. By Pascal’s day, the Jesuits had become the greatest political power brokers in France. (These are the years of the Three Musketeers and the devious Cardinal Richelieu. One for all, all for one! Of course, in later years, one of those musketeers fails to uphold that motto, and it all disintegrates… but I digress.)

As political operatives, however, the Jesuits had to tread carefully between royal power and the Christian mandate. What do you do with a king, for example, who very much wants to fudge the whole business of Christian morality and remain in good standing with the Church? (Think King Louis XIV and his many liaisons. You can’t very well deny the king Eucharist just because he’s, you know, being kingly with a few too many royal subjects.) What do you do? Well, you find practical compromises that “encourage” devotion while making room for, um, unfortunate peccadilloes and personal weaknesses. After all, an unyielding demand for the great work of a holy life would have led to ejection from the court, and then how would the voice of the gospel have been heard at all?

All this may seem particularly red-herringish if I now tell you, after all that, that Pascal was not, officially, a Jansenist. But his sister, Jacqueline, was a nun in a Jansenist convent, and he was, progressively, sympathetic to them, an apologist for them, and, finally, a man shaped by their spirituality.

Which brings us back to the Augustinian problem.** The truth is that what was self-evident and riotously fruitful in the 5th century had become increasingly disconnected from reality by the 17th century. The world had changed. It had both opened out (in knowledge, in imagination, in potential) and narrowed (through individualism, dissent, and personal opportunity).

Augustine’s vision of the expansive nature of the church and its nearly militant approach to infusing the world with the values of the Church was empowering in his time; it took the western world by storm and provided the scaffolding for a civilization that, in inculcating Judeo-Christian values and norms, contributed to the rise of the scientific revolution and democracy. But by the 17th century, the long ages of Christianization had had their cumulative effect in the western context to the point that Augustine’s vision had become narrow, rigid, and incompatible with the new humanist agenda. To adhere to his counsel would be (according to the Jesuits) to increasingly constrict the church; to reject curiosity, art, theater, music, and engagement with new cultures; to lose its place at the table in the hearts and minds of the people; in essence, to create a “besieged fortress” occupied only by the most devout, the purest of heart.

The emerging worldview—modernity—and the civilization that supported it, posed a critical choice for the Church: adhere to the Augustinian model and wither away, or modify the Augustinian model and survive.

“Both the Jesuits and the Jansenists contributed to the enfeeblement of Christian values, the former by their leniency, the latter by their intransigence.” (Kolakowski, 64)

Enough of all this—you see, I hope, some of the tension within which Pascal’s spiritual life developed. Jansenist in spirit, if not in fact. Yet also, a man very much the product of the very modernity the Jansenists condemned. A man poised between two worlds.

Now remove all the historical nomenclature, and see if we can’t resonate with some of this.

In my classes on spiritual formation, we often butt heads with the problem of the purity of the church. It comes up in questions about church discipline (as if there were such a thing, outside of heresy accusations); about the call to purity and the lament that deep down we relish our sin; about our own tainted witness to the world; about the nature of Christian community; about the meaning of the sacraments and the need for repentance. There seems an inevitable tension between a careful monitoring of the health and welfare of the church through draconian ways of enforcing some minimum standards of holiness, and an open, inclusive, welcoming embrace that invites inquiry and lets holiness rub off on the world.

“Expel the wicked man from among you” and “the unbelieving husband has been sanctified through his believing wife” sit pretty much side-by-side in 1 Corinthians.

We, like Pascal, are poised between two worlds, and the difference between them becomes greater every day. We compromise all the time. None of us are Jansenists, but frankly, my lack of perfection irks me. And your lack of perfection irks me even more. And when I read about the saints’ deep love for God, and their radical choices for holiness, I weep over my lukewarm soul.

___________________

Note to Reader: This series on Becoming Neo-Pascalian considers some of the ways Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) speaks into the 21st century. It draws from my own research, published in Beyond the Contingent (2011), and citations are from the book, unless otherwise noted. The beginning of the series is here: Introduction.

**For those of you really interested in the “Jansenist/Augustinian problem,” I recommend God Owes Us Nothing, by Leszek Kolakowski. My comments in this post rely on his work.