We are left with this all-important question: how do we get faith? How do we “make belief”? If we’re not lucky or blessed enough to have a Damascus-road experience, and, as Pascal tells us, we can’t reason our way to faith or merely don faith like a good habit, then what? What?

We are left with this all-important question: how do we get faith? How do we “make belief”? If we’re not lucky or blessed enough to have a Damascus-road experience, and, as Pascal tells us, we can’t reason our way to faith or merely don faith like a good habit, then what? What?

If indeed there is nothing we can do, why do anything? Might as well distract ourselves from the impasse. Right? We might as well remain passive and wait to be zapped, keeping ourselves busy with, oh, say good deeds and hard work and family life and career efforts and educational goals and fun adventures and, well, whatever takes our fancy.

Pascal recognized this attitude well. In his time, it characterized those he called dilettantes, those who dabbled in matters of the heart, never committing themselves but simply enjoying the show. Dilettantes, we could say, recognize the problem but really just can’t be bothered to tackle it since it is clearly unresolvable. Why put out all that energy and effort? This, Pascal insists, is itself a rejection of faith—far from “neutral” or even passive, it is an active choice to not believe. It may look benignly cooperative, but it is not. Spiritual “dilettantism” is hostile to faith.

Yet the futility of our human efforts to concoct faith, in Pascal’s mind, is greater than we can possibly imagine. As he describes it, the problem is not merely technical, as though we essentially have a broken circuit somewhere, or merely functional, as though we sit in a darkened room and, duh, fail to open the shutters. No, no, the problem is immeasurable, immense, beyond human conception. The problem does not lie in our minds, as though we need more knowledge; it does not lie in our experience, as though we need some ta-da! event we can point to; it does not lie in our senses, as though we could feel our way forward. No, the problem lies in le coeur, the heart, that center of our being where we are fully exposed to truth: about ourselves, about God, about the fullness of reality.

As Pascal puts it, a vast abyss falls between le coeur and God, an abyss before which we are helpless, stranded. On the far side, we perceive the hope of happiness, the fullness of all that we are meant to be, and yet we can only haunt the near edges of this void, looking for a way across. Can we bridge the chasm with relationships? leisure? entertainment? maybe knowledge? adventure? power? money? What about accomplishments? No? Okay, then, morality, religiosity, virtue? religious rituals? lots of Beth Moore Bible studies? a seminary degree? What? None of this will bridge the gap?

What else does this craving, and this helplessness, proclaim but that there was once in man a true happiness, of which all that now remains is the empty print and trace? This he tries in vain to fill with everything around him, seeking in things that are not there the help he cannot find in those that are, though none can help, since this infinite abyss can be filled only with an infinite and immutable object; in other words by God himself.

God alone is man’s true good, and since man abandoned him it is a strange fact that nothing in nature has been found to take his place: stars, sky, earth, elements, plants, cabbages, leeks, animals, insects, calves, serpents, fever, plague, war, famine, vice, adultery, incest. (f. 148)

[Yes, a rather odd list, I agree. Starts out all beautiful with stars and sky, and then we get to cabbages and leeks, which may be tasty, but I can’t say have been all that useful in satisfying my soul, and then we get to insects and the beginning of all things nasty. Go figure.]

Pascal spends a great deal of time talking about this Cosmic Divide. In his Pensées, he thrusts it in the reader’s face over and over again; he builds up a sense of bleak despair in the face of our utter helplessness, a shocking awareness of what he calls at one place “the knot of our condition” (f. 131). We become pinioned between this awareness of our need for God and the simultaneous awareness of the impossibility of reaching him.

The Christians’ God is a God who makes the soul aware that he is its sole good: that in him alone can it find peace; that only in loving him can it find joy: and who at the same time fills it with loathing for the obstacles which hold it back and prevent it from loving God with all its might. Self-love and concupiscence, which hold it back, are intolerable. This God makes the soul aware of this underlying self-love which is destroying it, and which he alone can cure. (f. 460)

Pascal’s notes record his own scramble for access to hope:

When I see the blind and wretched state of man, when I survey the whole universe in its dumbness and man left to himself with no light, as though lost in this corner of the universe, without knowing who put him there, what he has come to do, what will become of him when he dies, incapable of knowing anything, I am moved to terror, like a man transported in his sleep to some terrifying desert island, who wakes up quite lost and with no means of escape. . . . I see other people around me, made like myself. I ask them if they are any better informed that I, and they say they are not. (f. 198)

So. Our first tottering step toward genuine faith, wobbly and weak, must be a step toward our nothingness. This is counterintuitive in the spiritual world; we naturally grasp for fullness—even good fullness, religious or spiritual fullness, moral and virtuous and godly fullness—when we should be seizing our wretchedness with both hands, simply and honestly acknowledging that we have nothing, that we are, as scripture says “small and despised” (Ps. 119.41) or “poor and needy” (Ps. 70.5)

The dilemma is deeply personal, and if we want to see le coeur, we must look into the mirror of our soul. There, and there alone (and I definitely mean alone), we must interrogate the self and answer some very direct questions about our destitution. While we “try in vain to fill [our emptiness] with everything around us, seeking in things that are not there the help we cannot find in those that are,” we have no chance of attaining authentic faith. No chance.

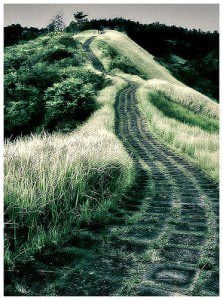

If we do not know spiritual hopelessness, we cannot hope. If we do not know spiritual wrechedness, we cannot find the happiness we long for. If we do not see the abyss at our feet, we cannot believe there is a way across it; if we are not willing to descend into its depths, which lie in our own souls, we will never ascend the heights on the other side.

Only by scrambling along that rough trail that seems to dwindle away into rocky nothingness, discarding along the way all the shiny gewgaws that disguise our poverty and distract us from our neediness will we ever find that narrow gate (Mt. 7.13). And that gate is the entryway to the Second Step of Faith.

Photo: riza, Flickr C.C.

___________________

Note to Reader: This series on Becoming Neo-Pascalian considers some of the ways Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) speaks into the 21st century. It draws from my own research, published in Beyond the Contingent (2011), and citations are from the book, unless otherwise noted. The beginning of the series is here: Introduction.