The English soul, according to Thornton, is Benedictine. Not Jesuit or Franciscan or Carmelite or Carthusian or even Cistercian. Benedictine. It goes with the homeliness of English spirituality, for Benedict’s charism was the way he created a home for the brothers, a place where they could work out their salvation, serve one another and the world, and grow in prayer and love. It has structure, but it isn’t crafted as rigorously as an Ignatian approach; it is rich in mysticism, but doesn’t pursue the ecstatic as the Carmelite way might; it invites passion, but embeds it more deeply in theological formation than the Franciscans.

Of course, even Benedict had to learn homeliness. His first experience leading a community didn’t go so well. His zeal for the spiritual life exceeded the expectations and interests of the brothers who had begged him to lead them. His spiritual rigor annoyed them to the point they felt they had only one option: poison the man. (Surely there were other options, but apparently early 6th-century exasperation had fewer restraints. Perhaps we should think of it as some primitive form of road rage.)

But Benedict, unlike many holy sorts, didn’t stomp off into the sacred oblivion of some dark cave to nurse his loftier way and let his weaker brothers fend for themselves. He learned from these fraternal would-be assassins about the frailty of the human will, the need for kindness and patience, the value of simple practices, and the reality of reasonable expectations. And thus he writes the Rule, a Rule designed to strengthen and support the reality of good intentions in weak human nature. (Check out Benedict’s Rule here. “To you, therefore, my words are now addressed, whoever you may be, who are renouncing your own will to do battle under the Lord Christ, the true King, and are taking up the strong, bright weapons of obedience.”)

Benedict’s genius was his (hard-won) wisdom about the imperfections of our nature and the powerful balm of rhythms and rituals. He combined work and prayer in a humming cadence of quiet, humble, and deeply human activities, articulated in his Rule, and thus changed the history and trajectory of European culture.

Thornton argues that the Rule established the threefold approach to prayer that is essential to all Christian living. This consists of the Office (praying through the liturgical prayers of the set hours), private prayer and devotions, and Mass (Holy Communion). Thornton makes some quite extraordinary (and debatable) statements when he argues that without the solid incorporation of these three habits, spiritual disaster is inevitable.

“Amongst all the tests of Catholicity or orthodoxy, it is curious that this infallible and living test, is so seldom applied. We write and argue endlessly about the apostolic tradition, about episcopacy, sacramentalism, creeds, doctrine, the Bible—all very important things—yet we fail to see that no group of Christians is true to orthodoxy if it fails to live by this Rule of trinity-in-unity: Mass-Office-devotion.” (76)

This may sound a bit draconian, for we all know faithful Christians and communities who have never heard of the Office and have never used liturgical prayers. Nevertheless, there are still angles on this Benedictine genius that we should consider, and there are many ways this Benedictine DNA has infused the heirs of English spirituality. Here are a few ways to think of our Benedictine heritage:

First, the Mass-Office-devotion trilogy could be reinterpreted as Church-devotion-awareness. Think of it this way. First of all, our spiritual lives must be Church-ordered. This does not mean that all our spiritual lives revolve around Church, Church activities, Church budgets, Church programs and projects. God forbid. Truly, God forbid. But it does mean that Church—the regular gathering for common worship, the celebration of sacraments, the ordered, expansive hearing of God’s Word, and the relationships and commitments that unfold within that community—is indeed the central engine of our formation. The Christian spiritual life is not an individual sport; it’s a team sport. And when we think or act as though we’re above the need for common worship, or we begin to believe it has no real value for our lives in Christ, we are exiting the arc of Christian history. Simon Chan argues that, “The church precedes creation in that it is what God has in view from all eternity and creation is the means by which God fulfills his eternal purpose in time. The church does not exist in order to fix a broken creation, rather creation exists to realize the church.” (Liturgical Theology)

Second, the work of the Office—that is, the regular reading of the prescribed prayers and scriptures for certain hours of the day (in Catholic tradition, Matins and Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, Compline, bedtime)—was derived from the Jewish pattern of prayer (think of Daniel praying three times a day). The Christian monastic Daily Office, with prayers or hours at seven times in each day, was based on the Jewish pattern of daily prayer at sunrise and at other times. The Anglican Reformation reduced the Office to morning and evening prayers. So leaving aside the recitation of specific prayers from the Book of Common Prayer, let’s just commend the rhythm of morning and evening prayer. Regular devotions. Quiet times, if that’s what you prefer to call them. The Benedictines took on a daily tempo of prayer, then work, then prayer, then work, then prayer. We, too, can take up the prayer-work-prayer tempo—a rigorous attention to a routine that sometimes rubs you raw, sometimes elates you, and sometimes puts you to sleep, and all the while shapes your soul in its responsiveness to the invitation of God.

Third, devotion then can refer to the moment-by-moment return, the quiet arrow prayers, the lifting of the eyes of the heart, the effort to be aware of the Presence throughout the day. Thus the weekly practice diffuses into daily practices, which reverberate in a steady act of yearning toward the Lord.

Mass = Liturgy/Worship

Office =Daily Devotions

Devotion = Practicing the Presence

That, I could argue, really is the foundation of healthy Christian spirituality.

The Benedictine Way has other riches that we could recover. Its three vows could provide some solid ground amidst the shifting foundations of contemporary life. Benedictine monks promised obedience—to an abbot, yes, which doesn’t help most of us, but the abbot was merely the embodiment of the Rule. We too need to turn our hearts in the direction of obedience, a most counterculture idea today, obedience to the Rule of Life. Benedictine monks promised stability—the steadfastness and grit of commitment to community, worship, and faith. Benedictine monks promised conversion—ah, this wonderful work of a lifetime of repentance, turning, turning, turning, and being healed.

A last Benedictine value, again, one that would be so powerful in these days: “All guests who present themselves are to be welcomed as Christ, for he himself will say: I was a stranger and you welcomed me (Mt 25:35).” All guests. Welcomed as Christ. The stranger, the traveler, the foreigner—welcomed as Christ. We may immediately want to translate that into public policy, but just take it personally right now. What would it look like for you to welcome others as Christ?

Next up: Bernard of Clairvaux.

NOTE: Navigate the series on English spirituality here.

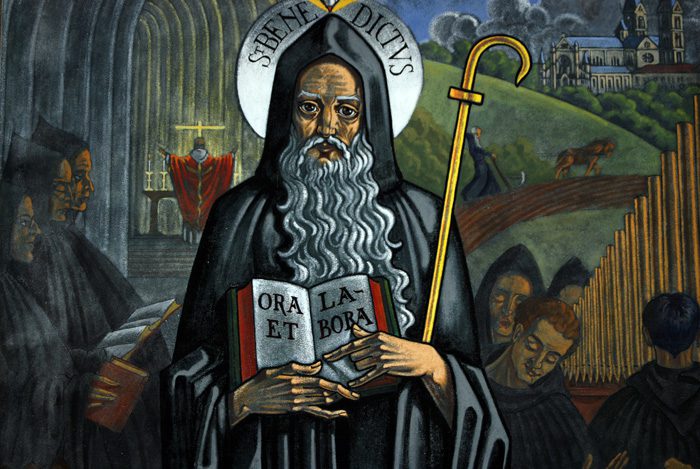

Image: Saint Benedict, Saint Meinrad Archabbey.