In exploring asceticism, or spiritual theology, for 21st-century Christians, I’ve been using Martin Thornton’s English Spirituality, a journey through the common Christian elements of the English tradition and the distinctive components that make it unique.

Thornton points out three ways English spirituality shares space with other Christian spiritualities:

- “It is elementary.” By this, Thornton means us to understand that Christian spirituality deals with the ordinary, the rhythms and practices of life that Christians take up everywhere in their response to the grace of God. We’re not talking about spiritual heroes; we’re talking about that lady in the pew with the teased, blue hair and the nine-year-old drawing a picture of the rector and the dad with the toddler perched on his hip. We’re talking about marital fidelity and parental patience and neighborly courtesy and professional integrity. We’re talking about the vows we take, the commitments we’ve made, and the acts of life that sustain those vows and commitments. We’re talking about the ways that we all know, through the Spirit, that prayer, worship, and sacrament are the sustaining lembas in our journey. [Lembas was the Elvish bread given by Galadriel to the Fellowship; it sustained Frodo and Sam through the darkness of Mordor. Lembas meant “journey-bread,” and evil beings could not touch it. I love that. Are we being sustained by the journey-bread that Our Lord provides?]

- “It is concerned with Christian progress.” Thornton points out that “progress” does not have anything to do with becoming super-spiritual or “prayer warriors,” but “rather with praying better in whatever way or state we happen to be.” It’s “life as it is,” not life as we read about it in the history books, but that “life as it is” becomes increasingly infused with prayer and increasingly sanctified. (And sanctified means, in part, committing fewer sins.)

- “It deals with Christian perfection.” Thornton is so helpful here, as he assures us that Christian perfection does not mean flawlessness. He’s not just doubling down on point #2 above—fewer and fewer sins until we don’t ever sin any more. That’s not what Christian perfection means. “Christian perfection admits of degrees and types … to be perfect, according to St. Thomas, means to fulfil the function for which one was created, and the Church embraces a diversity of function.” This is a bit like Paul telling us to remain in “whatever situation the Lord has assigned” (1 Cor 7.17). This is about being a more perfect me, a me-shaped Jesus.

But one way that English spirituality differs from these central themes is seen, as Thornton puts it, in the fourteenth-century addition of the word “homely.”

Now there’s a word that needs definition. We are not talking about homely as in unattractive, nor are we simply evoking general coziness, a Christian form of hygge. We’re not talking about firesides and warm socks, not talking about the Shire or the Cotswolds or log cabins and big blankets.

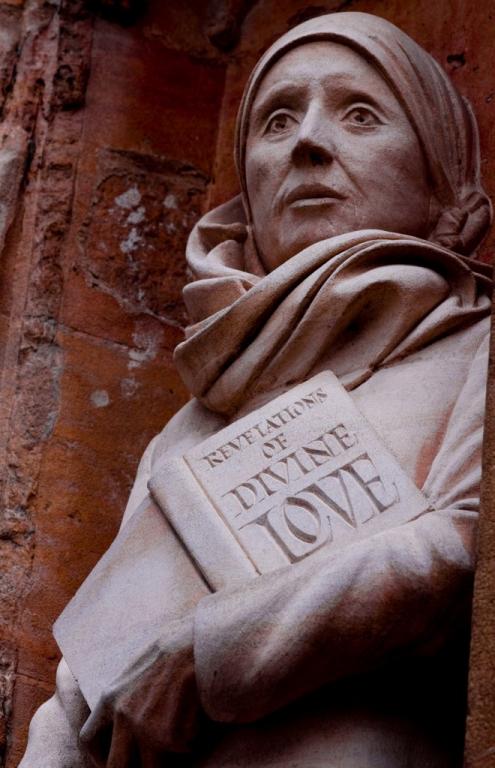

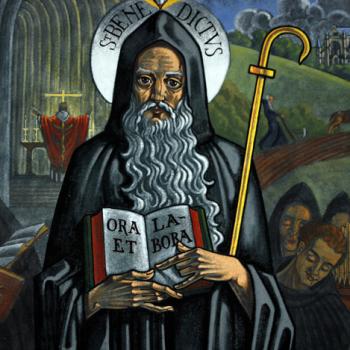

Julian of Norwich (1342-1416) introduces this word into her meditations, and Thornton teaches us that she uses this word to describe the domestic harmony of our lives with God. “’Homely’ means habitual, and therefore constant, calm, and, in the Benedictine sense, stable. … ‘Homeliness’ means that the ontological facts of the faith are to be taken seriously as the constant background of Christian life.” A homely faith is one that moves with the normal rhythms of the day, living peacefully in the knowledge of what Christ has already accomplished, without relying on intense feelings, without becoming self-conscious.

What a rich thought. A homely faith. A homely spirituality. England doesn’t produce many outsized spiritual personalities, like Catherine of Siena or Ignatius of Loyola or Martin Luther. Even the few that are, shall we say, a bit louder than the others—Margery Kempe?—have a homeliness about them that invites us into quiet, gentle rhythms of prayer and faith.

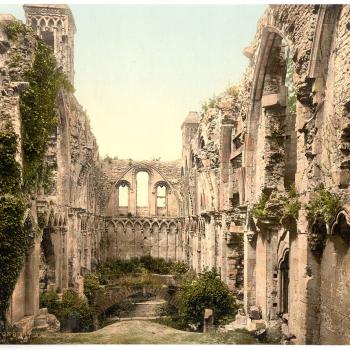

Image: Lothlorien, Nick Kenrick, C.C.

Image: St. Julian, C.C.