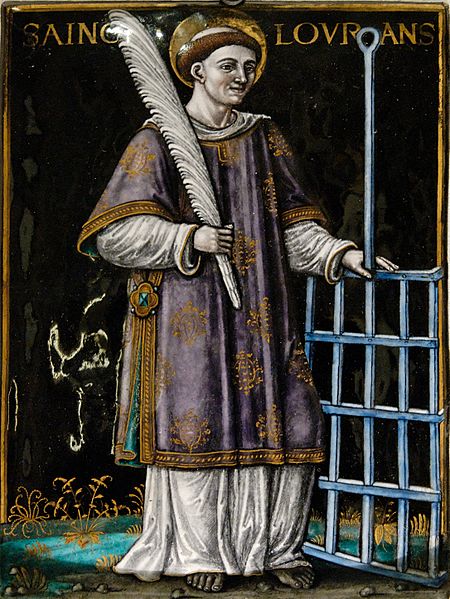

I recently spent a few hours in a couple of New York museums where at least twice I met Saint Lawrence in a painting. Each time, the artist put a gridiron (the grating kind for grilling, not the field kind for football) in his portrait, sometimes with flames licking his body. This third-century deacon of Rome was the one who, according to church tradition, succeeded in infuriating Emperor Valerian to the point that he was roasted alive as punishment. St. Ambrose tells us that as the emperor had encountered Christian communities, he had pillaged them of all their wealth. Knowing this, Lawrence had prepared for his confrontation with the emperor by taking the church’s wealth and giving it all away to the neediest in the city. When Valerian demanded of Lawrence the gold, silver, and jewels of the Roman Christian community, Lawrence asked for three days to gather its riches. On the appointed day, Lawrence presented the poor of the city, its weak, its elderly, its disabled—“here are the true riches of the church!” Valerian was unimpressed. The poor are not bankable.

Here again is Thornton’s definition of asceticism: “Ascetical theology makes the bold and exciting assumption that every truth flowing from the Incarnation, from the entrance of God into the human world as man, must have its practical lesson. If theology is incarnational, then it must be pastoral.” Nothing here about rigorous self-denial, though obviously Lawrence, our ascetic of the day, knew how to practice that. Instead, we have a focus on the pastoral, which demands all the courage and imagination of a Lawrence in the face of enormous cultural, political, and social pressures.

I think of Lawrence in the context of all that’s being written these days about Billy Graham. Some of the comments on my last post reveal the frustrations, bitterness, and hostilities of those who responded to Mr. Graham’s one-note song—of the good news about Jesus Christ—with bile and cynicism. Many clearly wanted Mr. Graham to focus on changing the world, rather than on changing hearts and visions. They wanted him to use his platform to rectify the cultural wrongs they have suffered, and they “roast him alive” for the ways they feel that he personally victimized them by his resistance to certain social and cultural changing mores.

Undoubtedly, there were those in the Roman church who felt that Lawrence could have done a better job in buying the emperor’s favor by actually giving him all the gold he could accumulate. Surely, they may have thought, there are better ways to make a point, tangible ways of averting an emperor’s wrath rather than provoking it, fixing the situation rather than exacerbating it.

As I “read” the American church today, I cannot help but feel that a great deal of Christian energy is being recruited to fixing the world. This is, perhaps, a necessary and long overdue correction to many centuries where the Christian’s energy went to avoiding the world, or shunning the world, or condemning the world, or neglecting the world, or abusing the world. I could go on.

Nevertheless, I think the call to Christian asceticism is a call to find a spiritual center to all that activism, a center that may be shrinking in our zeal to work for justice. Thornton writes this, rather presciently I think:

“The Church concerning itself primarily with cultural and social activities must fail, for it is but substituting one kind of materialism for another. It is significant that the American Church, with all the money and practical appurtenances it needs, is now worried by its own ‘activism’ which is but an American term for Pelagianism.” (Thornton, 7)

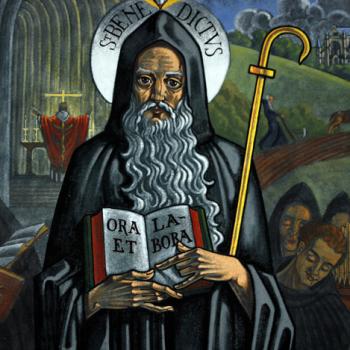

[Poor Pelagius, a zealous British monk who goes down in history with an -ism attached to his name. The short version of his heresy: Pelagianism suggests that indeed we can and should merit the grace of God by our rigorous efforts to keep the commandments of God. The Church decided long, long ago that grace really means grace, unmerited favor, and that we cannot ever satisfactorily keep God’s commandments to the degree that we could stand before him in our own righteousness.]

So are we today becoming neo-Pelagians? Have we made our political postures, our cultural causes, our social activism the measure of our righteousness? Have we decided that indeed we can and should fix the world, and thereby we are saved?

Simon Chan says that spiritual theology, what Thornton calls ascetical theology, is the bridge between systematic or theoretical theology and practical theology. The former—systematic or theoretical—addresses the ideas and beliefs of authentic Christian life, while the latter addresses the application of those ideas.

“In the narrow sense, spiritual theology is concerned with life in relation to God (the supernatural life), whereas practical theology is more broadly concerned with action in the world. … The importance of the place that spiritual theology occupies between systematic theology on one end and practical theology on the other cannot be overemphasized. Without the mediation of spiritual theology, Christian praxis is reduced to mere activism.” (Chan, 19)

In the same way that our society is becoming increasingly polarized into right and left, hard conservative and hard liberal, many Christian voices are bifurcating the ancient seamlessness between biblical truth and the pursuit of justice, between the Te Deum and works of mercy. The church has always taught that they are one and the same, the visible expression of an internal trust in divine revelation, faith working itself out in love. We may say we want to integrate these, but without spiritual theology, or ascetical theology, we cannot help but “take sides.” In cultivating the ascetical side of our faith, we explore “the fundamental duties and disciplines of the Christian life, which nurture the ordinary ways of prayer, and which discover and foster those spiritual gifts and graces constantly found in ordinary people.” (Thornton, 19)

So, dear Saint Lawrence, I’m sorry for whatever gruesome death you suffered, but I thank you for your willingness to bear Valerian’s wrath for the sake of the gospel. I thank you that, somewhere along the line, long before Valerian reached Rome, you both confessed your faith in Christ and cultivated a generous heart. I thank you for your courageous and imaginative posture of both faith in the Christ who is worshipped and love for his people.

NOTE: Navigate the series on English spirituality here.