All the cool girls, that is, Rebecca Bratten Weiss over at suspended in her jar and Mary Pezzulo (see Mary, you’re definitely at the table) at Steel Magnificat, are talking about modesty, so it seems prudent to hitch my star to that bandwagon. These two ladies have already discussed modesty in terms of power and subjectivity and the pornographic gaze that reduces subjects to objects, respectively. Now, this might sound weird given that I recently talked about how topless picnics use the body to send a message; nevertheless, to look starkly at modesty, the fact is, it’s really not really about hem lengths.

I know, I know, I know. Thank goodness for Bad Catholic changing up the Google results there. And, yet, I found Rebecca’s insight particularly intriguing. Looking at the origin of modesty as a Christian virtue, she turns to etymology and finds key Scriptural texts on modesty (1 Timothy 2:9-10, 1 Peter 3:3-4, and Matthew 6:1) use :

The Greek word…kosmios (a derivative of kosmos) meaning orderly, well-arranged, decent – a harmonious arrangement…This modesty that is decent and orderly must be seen not as passivity or absence, but as a certain right-ordering in action, a kind of restraint, a refusal to succumb to the temptation to use one’s gifts or powers in order to lord it over others, to manipulate them, to overwhelm them.

What intrigued me about this is how closely her observation that modest has to do with not using a gift or power to gain hold over another aligns with the four areas of life St. Thomas saw modesty as relating to: 1) the desire for excellence that exceeds our ability (i.e. pride); 2) the desire for knowledge in order to take pride in your own knowing; 3) acting in a manner befitting our role and the circumstances we find ourselves in; and, 4) wearing clothing and apparel in a manner that does not seek excessive attention or take excessive pleasure in the clothes themselves. Of the 11 questions and 34 articles in the Summa (that’s mid-1200s that we’re looking at, fam) which St. Thomas Aquinas devoted to exploring modesty in all its particularity, only one article addresses women who attempt to provoke men to concupiscence (concupiscentiae), a word we might we might literally read as “desiring” and colloquially read as “lust.”

Rather than treating in excruciating particularity about this or that item, what St. Thomas instead talks about while exploring this virtue, is how the particular practice of modesty is ultimately about our relationship with God, inasmuch as we are ordered to communion with other human persons out of our love for God.* The Catechism of the Catholic Church, after speaking about it more immediately in terms of purity, notes that “purity of heart requires the modesty which is patience, decency, and discretion. Modesty protects the intimate center of the person.” (CCC 2533). This all suggests that, returning to Rebecca’s point, modesty as a virtue is greater than what a tape measure can measure.

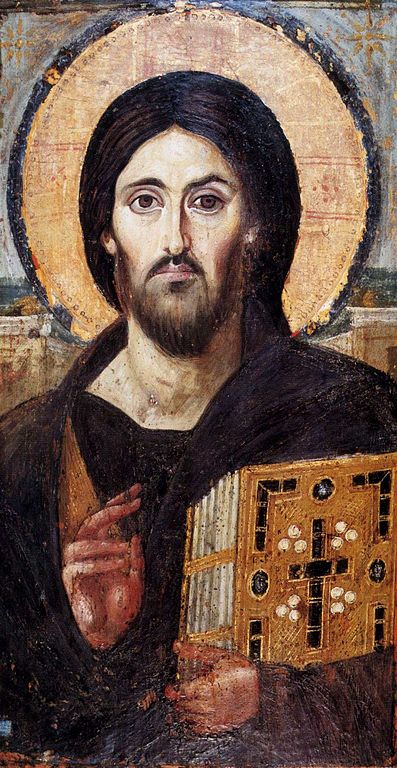

Like it’s much abused sister chastity, modesty is often reduced to a laundry lists of “this not that, here not there.” If we turn to Christ and what he taught us about being human, we discover that modesty has far more to do with positively acting, rather than with simply not wearing pants.** Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange wrote that “He who was the Word of God and could awe everyone chose to live for thirty years a hidden life working at the most commonplace trade.” Christ became man, suffered, and died for us in order that he might “enable men and women themselves to experience again the compassion of God…[by being freed] to accept God’s love” and in that acceptance enter into union with God.

After all, Christ Himself is the ultimate model of modesty. For Christ,

though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God something to be grasped. Rather, he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, coming in human likeness; and found human in appearance, he humbled himself, becoming obedient to death, even death on a cross.

Christ humbly assumed the form of a slave, so that He might be made like us, so that He might redeem us, by “laying down his life for his friends” out of His love, calling us to communion. Christ, Who is our greatest good and desires us to enter into union with Him through incorporation in His Church, assumed a human nature to Himself so that we who were dead to sin might live in Union with Him.

Christ’s humility suggests that modesty is a virtue that creates the conditions for communion between disparate parties: in this case between God and man, resolved in Incarnation of the Word—the Word made flesh, dwelling among us. This idea of modesty as preconditioning interpersonal communion can be seen in many ways: take soon-to-be Saint Mother Teresa of Calcutta’s habit: the Missionaries of Charity modeled their habit off the simple clothes of India’s poor. Or the athlete who plays sports with children with various diseases, and doesn’t simply dominate the entire game, to create an equality between himself and the others. Or the man who drives a Honda around his country home town, though he has a Ferrari parked in his beach house, in order to not overwhelm those he works with by wealth, along with the authority we so often associate with such wealth.

And it should be said, because even St. Thomas devotes an article to it, modesty moderates our expression of sexuality. Not because sexuality is bad. Not because a display of skin by men or women will necessitate the other entering into a downward spiral of sin. Not because women are bad or men are bad or the body is bad. But because integrating our sexuality can be hard at times. So we practice modesty, holding back some of what we could reveal. We do this not because the body is dirty, but because our sexuality can, given the Fall, conflict with establishing the conditions allowing for interpersonal communion between men and women (which goes for men just as much as for women). Certainly, as St. Paul said, “to the pure all things are pure,” but many of us are not yet able to enter into communion with other persons without being overwhelmed by the external trappings of wealth or prestige or intellect or athletic prowess or even the body as masculine or feminine.

Modesty, in fact, is an important virtue for this day and age when not only equality, but also equity are such important topics of conversation. Modesty allows for the equality of friendship because the one with more power to impress, with greater power to remove those conditions, goes beyond what is asked and serves the other by releasing, intentionally setting aside, or acting in such a way as to explicitly overcome the disparity. Another way to put it would be to say that in concerning ourselves with the practice of modesty, we ought to look to Christ as our model, Who, after washing the disciples feet, said to them, “I have given you a model to follow, so that as I have done for you, you should also do.”

So practice modesty—not by reaching for the smelling salts, but by setting aside, when the situation calls for it, the things in your life that prevent others from authentic, interpersonal communion, whether that be your fast car, your ability to quote German philosophers in conversation, your athletic prowess, or your speedo.***

*i.e. St. Thomas writes that humility (ST.II-II.161.1 ad 5) “Regards chiefly the subjection of man to God, for Whose sake he humbles himself by subjecting himself to others.”

** You can google that one on your own. Truly.

*** Here’s *not* looking at you, Michael Phelps and Nathan Adrian.