I’ve consistently encouraged pastors to put their best prophetic foot forward when it comes to addressing controversial justice issues in the pulpit. But here’s the truth many clergy have shared with me – they are afraid to preach about issues of public concern. They know their preaching should in some way address things like racism, homophobia, climate change, sexism, economic issues, or hatred of foreigners, for example. But fear holds them back, keeps them quiet, and muzzles their prophetic voice. How can you preach when you are afraid?

Why are clergy scared to preach about issues of public concern?

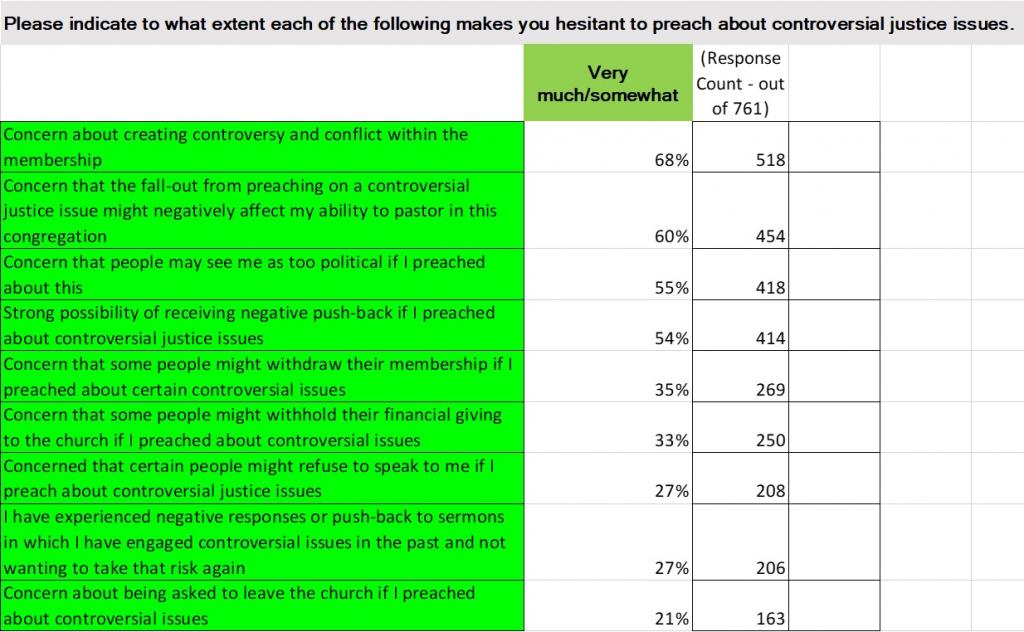

That’s one of the questions I asked in a survey I conducted of over 1200 clergy – one of the largest surveys on preaching and sermon content ever done in the United States. As part of my research into how preachers are approaching their sermons during this divisive time in our nation’s history, I designed and sent out a 60-question online survey directed to mainline Protestant clergy serving congregations in the United States. The survey, “Preaching about Controversial Issues,” ran for six weeks in 2017, from mid-January to the end of February, and explores a range of topics, including the reasons clergy list for either engaging controversial topics in their sermons or avoiding them.

Pastors listed many reasons holding them back from preaching about justice issues, some of which are based on biblical, theological, or personal principles (which I’ll discuss in a future article). But for more than half of the pastors surveyed, the reasons for not addressing issues of public concern boiled down to four main fears:

- Fear about hurting or dividing their congregation

- Fear about risking their ability to effectively minister in their church

- Fear about receiving negative push-back for being “too political”

- Fear about loss – loss of members, money, and their own jobs

“I feel like a coward.”

Take, for example, the recent events in Charlottesville, Virginia, where the Ku Klux Klan, Nazis, and white nationalists descended on the city, injuring and killing counterprotesters. I and other have been urging clergy to take a public stand on the issues of white privilege, racial hatred, anti-Semitism displayed in Charlottesville, by Donald Trump, and other defenders of the white agenda. But a pastoral colleague recently shared with me the realities of his church context:

“I sit in the middle of a town that time forgot. I’m a ‘blue dot’ in a ‘red’ church. My job depends on my ability to preach and teach the congregation in a way they can accept, and any controversial topics could negatively affect my position. I need my job. But I feel like a coward because I’m not able to be as prophetic as I want. The previous attempts by another minister were met with so much backlash that I’m scared to even ‘go there’ with them.”

A majority of clergy worry about their sermons creating controversy

This pastor is not alone in his fear about preaching about controversial justice issues. As you can see from the chart below, according to responses in my questionnaire, nearly 70% of clergy surveyed expressed hesitancy to preach about controversial topics for several reasons.

Most of the hesitancy stems from genuine concern about the relationships within the congregation – both between them and their parishioners, and within the church itself. Concern about creating controversy and conflict within the membership ranked number one. Concern that the fall-out from preaching on a controversial justice issue might negatively affect one’s ability to pastor in their congregation came in second.

Anger, the silent treatment, and leaving

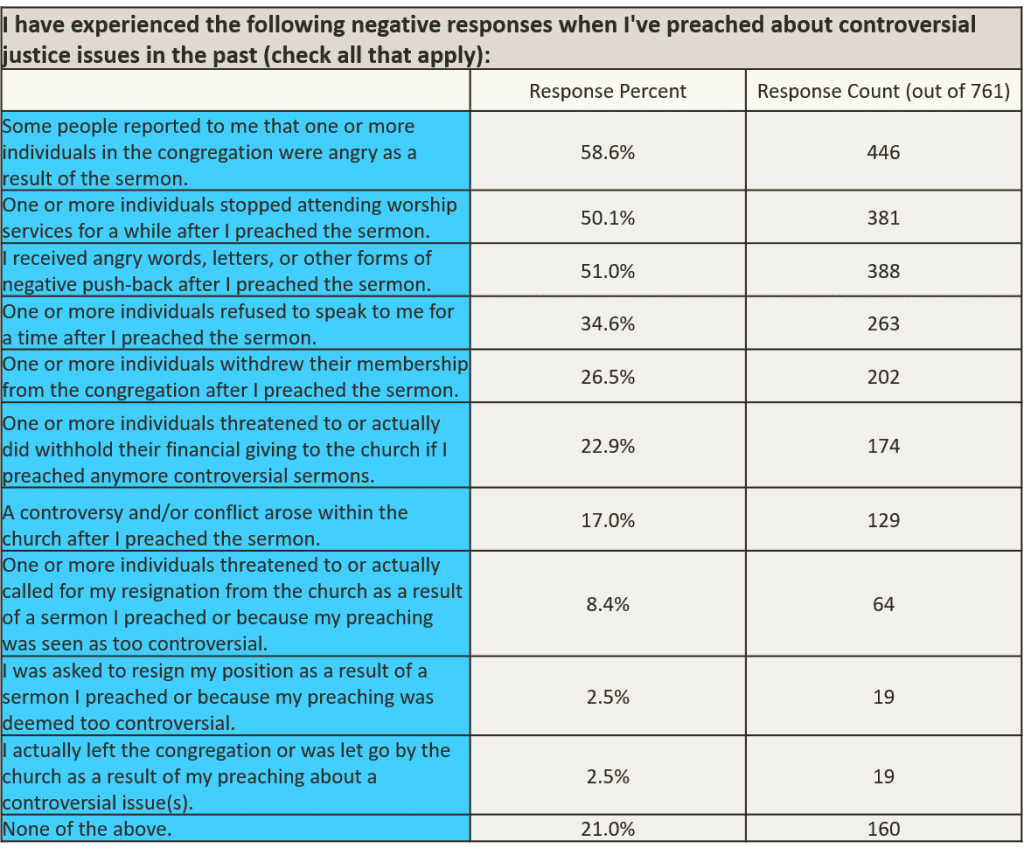

Other pastors are concerned that people might be so angry with them for preaching prophetically, they will retaliate in any number of ways. Consider these responses to the question about whether clergy have experienced negative push-back from their sermons about controversial justice issues:

Real pastors, real fear

Now consider some comments that came from different clergy about what they have experienced as a result of their preaching:

- “I have lost members over the past two years due to preaching about race. There’s only so many losses a small congregation can handle.”

- “I have concern that my boss might berate me or make me apologize for what I’ve preached.”

- “I have received threats in the past and worry that they might be acted upon if I continued to speak as freely as I would like.”

- “I am in the midst of leaving my congregation because they did push back saying I was too political. I chose to leave to avoid causing more issues. I would rather leave than stay and be afraid to speak what I feel God is calling us to action.”

Threats, intimidation, withholding of financial support, abandonment – if this were a relationship between two people in a family, we would call this domestic abuse. It’s no wonder some clergy in certain congregations are afraid to preach about justice issues.

The difference between being “political” and being “partisan”

This is not to say that there aren’t justifiable reasons to be cautious when preaching about contemporary issues. I’ll be addressing this more in a future post. But, briefly, many pastors stress their belief that the pulpit is for preaching the gospel, not engaging in partisan politics.

This is true in one sense. But such a belief is predicated on the false notion that that the gospel has nothing to say about contemporary issues or current events. What I teach my students is that there are ways to address issues of public concern without being partisan (promoting a particular political party). Remember that the root of politics is polis, which in Greek refers to “community” and “citizens.” In that sense, Jesus himself was very “political” because he consistently addressed issues that affected individual citizens and the entire community. And, yes, it did bring on the wrath of those in power. And they put him to death.

But preachers do not have to be like Jesus and die for the gospel. Jesus already did that. Of course, many do choose to put their lives on the line for the sake of the gospel, and thank God for the sacrifices they have made. But there are many ways to be faithful proclaimers of the Word without succumbing to quietism or opting for martyrdom.

How do I preach if I’m afraid I’ll say the wrong thing?

If you are one of those pastors who wants to preach prophetically, but is afraid for any of the reasons listed above, below are some suggestions. This is not a complete list, of course, because this is a work in progress (see “The Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red/Blue Divide”). But we’re in a time of crisis in this country, so this is intended as a word of encouragement and practical advice.

1. Let the biblical text guide you to lift up the “big questions” that underlie the headlines or controversies.

Leonora Tubbs Tisdale, in her excellent book Prophetic Preaching: A Pastoral Approach, names rootedness in biblical witness as the first component of prophetic preaching. If you don’t feel comfortable taking a stand on an issue, you can at least articulate the questions that arise from the issues and frame them in in biblical and theological terms. Key questions might include:

- What does God want for us?

- Where do we find similar situations in the Bible?

- Where or how do we see the Triune God at work?

- What teachings and actions of Jesus might be helpful here?

- Where are signs of hope that the Spirit is showing us?

- What is God calling us to do?

- What kind of Christians shall we be in light of this?

2. Ask yourself: What is breaking my heart the most right now about what’s going on with our nation?

And then ask: if I were sitting in a pew where the pastor was intending to preach of word of truth, hope and love, what would I want to hear in the sermon? [For sermon approaches to answer this question, see O. Wesley Allen’s Preaching in the Era of Trump (St. Louis, MO: Chalice Press, 2017).]

Remember – you are the first hearer of your sermon. If what you preach is not speaking to your own heart and mind, how can you expect it to reach others? This is not to say that you should get on your soap box or use the pulpit as therapy. But it’s okay to be honest about how you feel. Emotions are messengers. The Bible is replete with examples of God’s people being honest about their fears, anger, joy, confusion, and outrage over the events of the world around them. God can work with those authentic feelings.

3. Invite conversation after the sermon.

Offer an opportunity for a round-table discussion and/or Bible study about the issue so that the sermon will not be the final word, but a word of invitation for community-building. Be sure to use ground rules for engagement, and to brush up on your facilitation skills so that the experience will be healthy and productive. Read John McClure’s The Roundtable Pulpit: Where Leadership and Preaching Meet for guidance on how to include parishioners in discussions about biblical texts and how to incorporate the conversations into future sermons. This is not about having a debate or coercing people to change their minds. It’s about transforming the culture of the congregation from one of divisiveness (or avoidance) to one of healthy conversation that enables God’s justice to take root and grow.

[Also see these very helpful books:

Under the Oak Tree: The Church as Community of Conversation in a Conflicted and Pluralistic World, Allen, Ronald J., John S. McClure and O. Wesley Allen, ed., (Eugene, Or: Cascade Books, 2013)

Difficult Conversations: Taking Risks, Acting with Integrity, Katie Day (Alban Institute: 2001)]

4. Find ways to build bridges. Lift up the core values different viewpoints have in common.

Peace, nonviolence, fairness, safety, meaningful work, and healthy relationships are all common values we can share, even as we debate about how best to go about achieving them. When preachers remind their congregations of these values, they help to anchor the community in God’s intentions. Raising up the vision of hope, forgiveness, and reconciliation that is given by the prophets and Jesus is a way to elevate the conversation above the partisan fray.

5. Admit your own complicity and struggles with the issue.

Avoid inadvertently setting yourself above and/or apart from the congregation in self-righteousness. Finger-wagging only creates unnecessary and harmful distance between pastor and congregation. (See Lucy Atkinson Rose’s book Sharing the Word: Preaching in the Roundtable Church [Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox, 1997)]. Instead, share about how you have come to change your mind about something, how you were once “blind” but now see. Sharing your humanity and vulnerability can help open space for prophetic critique.

6. Use the power of silence, ritual, prayer, and liturgy to hold these powerful emotions and big questions.

If you are truly averse to speaking about an issue, or discern that the sermon is not the place to tackle it, at least offer some acknowledgement of the event or issue through prayers or some other aspect of the liturgy. A few minutes of prayerful silence during worship can hold and sanctify all that we bring to it. Setting up a table full of tea light candles and inviting everyone to light one can provide both prayerful agency and evoke peace in the midst of a chaotic time.

Worst case scenario

Even with your best intentions, there is a risk that even asking the questions about these issues or naming certain current events in your sermon can cause a swift and negative reaction. So take steps to prepare for that possibility:

7. Have preparatory conversation with your board or parish-staff relations committee ahead of time.

Alert key trusted leadership that you’ll be addressing a sensitive topic so that they are not surprised and can “cover your back” if people come to them complaining about your sermon.

8. Prepare to engage in pastoral follow-up with those who might be angered by your sermon.

Ask to meet the person for lunch or coffee. Or to visit them at their home. And then listen to them, while asking clarifying questions. I served three different congregations during my 16 years of ministry. When I responded to negative push-back from parishioners by talking with them later, we never failed to reach a new level of respect and understanding – even if we did not see eye to eye.

Above all – build trust through pastoral relationships.

Think of the ways you have shown your love for your congregation. Visiting them in the hospital. Sending them a card. Speaking kind words. Teaching their teenagers. Thanking them for their service. Visiting their relative in the nursing home. Being there when the last breath is released. All of this will go a long way toward opening their hearts and minds for what you have to say in your sermon.

If they know you love them and that you sincerely have their best interest at heart – as well as the best interest of preaching God’s Word – this will help to create the relationships that model the kind of healing your sermon proclaims.

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary (Kentucky) and author of the book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). You can follow Leah on Twitter at @LeahSchade, and on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/.

For more on preaching about Charlottesville, white supremacy, white privilege, racial hatred, and anti-Semitism:

9 Reasons You Need to Preach about Charlottesville

How to Preach When You Are Afraid

8 Ways to Preach about Charlottesville, White Supremacy, and Racial Justice

The Harp Sermon: A Response to Charlottesville and Racial Hatred

Psalm 137: The Beautifully Dangerous Psalm

“Courage” poster courtesy of: blog.wickerparadise.com/post/60731177737/courage. Some rights reserved.