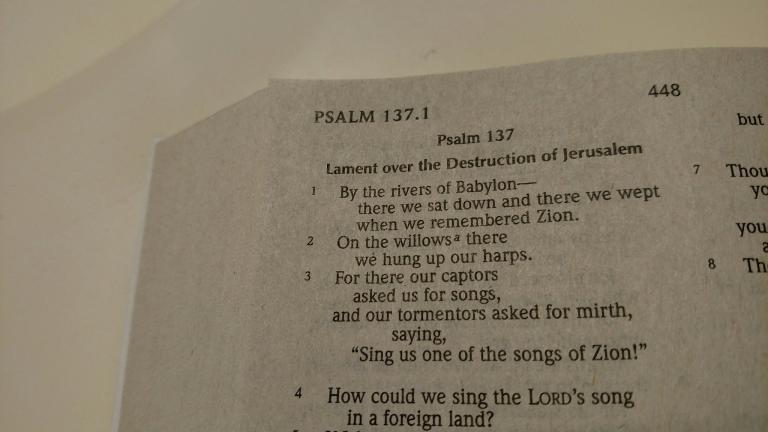

Psalm 137 is rarely ever used in worship. Why? Because it is a dangerous psalm. But we need to read it, study it, and listen to the voice of anguished rage. Because God is listening to those voices as well.

Have you ever listened to the song, “On the Willows”?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RcgRQT8L7Zw

I remember the first time I heard this music from Godspell. What a beautiful, mournful song, I thought to myself. And I know I’ve heard those words before . . . “On the willows there we hung up our lyres.” Such beautiful, haunting words. Where have I heard them before? And then it hit me – Psalm 137. But I noticed that the song’s lyrics stopped short of the last verses of the Psalm: “Happy will be the one who does to you what you did to us, O Babylon. Blessed will be the one who dashes your little ones, your babies against the rock.”

What an awful image!

It’s hard to believe a Psalm like this is in the Bible. It is so violent! It speaks of killing babies, of all things. This is a far cry from Jesus’ words of forgiving your enemies and those who persecute you.

This is raw, uncensored hatred and desire for revenge. Most people don’t even realize this Psalm is in the Bible. In fact, a previous version of the ELCA hymnal, The Lutheran Book of Worship, even censored out this psalm altogether from its collection.

Why? Because it is a dangerous psalm – a beautifully dangerous psalm.

[Watch the video of this sermon: https://www.facebook.com/glclex/videos/1385217761586027/]

So why is Psalm 137 in the Bible? What are we to do with a psalm like this?

The presence of this kind of violent and vengeful language is off-putting to many people. Some may even claim that this kind of wording authorizes revenge and retaliation. So we have to handle this psalm with care. Used in the wrong way, it could serve as an excuse to continue the cycle of violence and result in further bloodshed.

But we must also be careful in our reading here.

The psalmist is not saying that we should go out and kill children and seek revenge.

Yes, it is expressing those thoughts and those wishes. But it’s done as a prayer to God. And that’s a very different thing than acting on those feelings and carrying them out.

Let’s be honest – “desire for retribution and violence are in fact part of the human condition.” (Murphy, 43). Think back to the vitriolic language that erupted after the attacks on our country on Sept. 11, over a 15 years ago. I heard more than one person say, “We should just bomb the whole Middle East. I don’t care if we kill their children – might as well get them before they grow up to be terrorists and attack us. Let’s just bomb them back to the stone age!”

And . . . we have. We may not be personally bashing babies’ heads in. But our bombs and our guns have taken the lives of countless innocent children – so-called “collateral damage.”

Yes, these are difficult words to hear.

Here we are worshiping in this beautiful church with our friends – we don’t like to talk about these things. We don’t like conflict, and we just want to get along and be good people. So a psalm like this is embarrassing, even offensive to us.

Why? Because most of us have never “lost that much, been abused that much, or hoped that much,” (Brueggemann, p. 75). It is so difficult for us to pray this psalm because we simply cannot identify with it. So what are we to do with it? Is there another approach to this beautifully dangerous psalm? Yes!

Here’s what we must do: We must listen to the voices of Psalm 137.

We must hear the agony and even the expression of the desire for sinful violence. And we must listen to Psalm 137 precisely because it is said in the context of prayer. “These expressions of rage exemplify the demonic in every human heart. . . When they are heard in prayer, they serve to illuminate our own feelings and even to accuse us of our own acts of vengeance.” (Murphy, 46).

We live in a world marked by violence and revenge – wouldn’t it be prudent to put those feelings into a context of prayer instead of acting on them?

Wouldn’t it be wise to invite God into these feelings?

That’s just what the psalmist does here. You see, we have to understand the specific historical event that this psalm makes reference to. This psalm reveals the sufferings and sentiments of people who experienced first-hand the terrible days of the conquest and destruction of Jerusalem in 587 B.C. This was their September 11. Their temple was destroyed – the very center of their faith.

And, like the Africans who were brought to this country against their will, the Hebrews were forced into the Babylonian captivity. They were taken far from Jerusalem and subjugated as slaves of the Babylonians. Even worse, they watched their conquerors kill their children. “Adults might be spared to serve various purposes for the conquerors, but the infants were killed to end the community’s future.” (Eaton, 455).

Psalm 137 is a psalm for this moment.

Because these words from the Bible help us understand why African Americans are so upset to see monuments to their enslavers. It reinforces the humiliation they suffered and reminds them of their enslavement. And this resurgence of Nazis reminds Jews of the threats of annihilation they have faced throughout history. It’s why so many people are standing against the KKK and Nazi rallies around the country. Because white nationalists want to repeat the horrors that led to the expression of these words in Psalm 137.

When the Israelites were captives in Babylon, they experienced profound homesickness, grief, depression, and despondency. This scene from the psalm describes the Hebrew musicians sitting by one of the rivers in this hated land. Their captors come along, taunting them, ordering them to sing happy songs about Zion. What an ignorant, arrogant insult. Of course they cannot sing happy songs about Zion in this foreign land. The holy songs cannot be sung on ground not dedicated to the Lord. To do so would be sacrilegious and bitterly ironic.

So they hung up their instruments in protest.

This kind of thing actually happened in the Nazi death camps, where Jews were forced to sing and dance their music and songs while the soldiers mocked them and laughed at them. “It was a part of the humiliation intending to rob Jews of their identity, their dignity, and their hope,” (Brueggemann, p. 75).

Never forget.

The psalmist then makes a personal vow not to forget Jerusalem. To never forget the Temple that has been leveled, the city that has been burned, the king and leaders and musicians and teachers who have been led away to captivity in Babylon. And then with a fury that nearly explodes from the page, he wishes for someone to exact revenge on the Edomites who plundered Jerusalem after the Israelites were gone, and upon the Babylonians who so mercilessly killed their children.

We can only look upon these feelings with either stunned horror or detached numbness.

Because unless you have lived through something similar, I don’t think any of us have ever experienced this kind of suffering. In fact, we want to keep that kind of suffering far away. We don’t want to hear about the history of slavery and Jim Crow. We don’t want to hear about the Holocaust and anti-Semitism. It’s so much easier to forget the ugly history of what Europeans did to the native peoples of North America. We don’t want to deal with the woman who has been brutally raped.

We cannot bear such suffering.

So we avert our eyes, shush their voices, blame them for what happened, or even deny that it ever happened in the first place. And sometimes we express outrage that such intensity of pain and desire for revenge is even voiced, much less in the Bible. Some people are probably upset that we are even talking about this in church.

I can tell you that there are pastors across the country who have been working diligently and faithfully to figure out how to preach during this difficult time. And some of them will get negative push-back for talking about these realities. “Can’t we have just one hour in the week when we don’t have to think about these things?”

But Old Testament historian Walter Brueggemann suggests that it is absolutely necessary to listen to this Psalm. Because it speaks with unfailing honesty about the abuse that was done, and is still done, to individuals and to whole groups of people. And it is necessary for us to hear how it feels to suffer this kind of violence and humiliation. We want to move so quickly from this Psalm to Jesus’ words telling us to forgive. But, as Brueggemann asks, “Could it be that genuine forgiveness is possible only when there has been a genuine articulation of [anger] and hatred?” (Brueggemann, 77).

How to help them heal

We need to recognize that healing is not just something we long for in our own bodies and in our personal relationships. Healing is something that is needed by our brothers and sisters around the world who have experienced the most humiliating kind of brutality. By listening to their words, hearing their stories, believing them, and holding those powerful, violent emotions as best we can, we are at least acknowledging that, yes, this has happened. It’s not fair, it’s not right, and your pain is worthy of healing.

Psalm 137 gives permission, and actually authorizes the powerless who have been brutalized to vent their indignation and turn to God for justice. “It is an act of profound faith to entrust one’s most precious hatreds to God, knowing they will be taken seriously.” (Brueggemann, 77). And that is, finally, where we must direct our prayers.

Emmanuel – God with us

I invite you to come forward to this table of candles as we sing the hymn, “O Come, O Come Emmanuel.” Yes, this is an Advent hymn, but it is so appropriate for those who are mourning in lonely exile, as the Israelites did, as the slaves did, as the Native Americans did, as so many refugees do across this planet, and as so many suffer in our world today. This hymn asks for God’s presence. That’s what Emmanuel means – “God with us.” And we can certainly all agree that we need God’s presence with us in our nation, in our world.

Maybe you’ll light a candle as a symbol for your own need for healing. Or maybe you will see the candles and remember that someone is burning with pain and rage which needs to be seen and heard and healed. Maybe you are even feeling anger yourself right now. And that’s okay. Give that anger to God, and let God transform it.

O Come, O Come, Emmanuel – God is with us. Amen.

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary (Kentucky) and author of the book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015).

You can follow Leah on Twitter at @LeahSchade, and on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/.

For more on preaching about Charlottesville, racism, and white privilege:

9 Reasons You Need to Preach about Charlottesville

How to Preach When You are Afraid

8 Ways to Preach about Charlottesville, White Supremacy, and Racial Justice

The Harp Sermon: A Response to Charlottesville and Racial Hatred

Sources:

* Brueggemann, Walter, The Message of the Psalms: A Theological Commentary, Augsburg Publishing House, 1984.

* Eaton, John, The Psalms: A Historical and Spiritual Commentary withe and Introduction and New Translation, Continuum, New York, 2005.

* Murphy, Roland E., The Psalms, Job, from Proclamation Commentaries, Foster McCurley, Editor; Fortress Press, Philadelphia,1977.