The Wall Street Journal headline read: “The Flynn Entrapment.” Fox News jumped in with its own headline: “Judge in Flynn case orders Mueller to turn over interview docs after bombshell claim of FBI pressure.” All this was in response to Michael Flynn’s lawyers’ assertion that he had been tricked by the FBI into lying. “Ugly tactics” were used, they said. The Feds didn’t warn Flynn that it was a crime to lie.

Really? A retired U.S. Army Lieutenant General needs to be told that it is illegal to lie to federal investigators?

As I thought about this developing story, I flashed back to my own experience with a kind of “entrapment” that caught me in a lie when I was eleven years old. And I remembered the indelible lesson it taught me.

His name was Quasimodo.

He was the bulldog my father brought home to be our new pet. When I first learned our family was getting a dog, I had visions of a cute puppy who would romp in the yard and curl up in my lap. Instead, here was this grotesque creature with nonstop slobber and eye goo that would drip into the wrinkles of his face. Like his namesake from the Victor Hugo novel, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, he had a kind heart and gentle soul. But his awful smell and slimy jowls disgusted me.

Yet it was to be my job to walk the dog every day when I came home from school. My father sat me down in the kitchen and showed me the brand new leash he had bought. “You take this leash out tomorrow, clip it to his collar, and take him for a walk around the neighborhood so he can get some exercise, okay?”

I nodded, reluctantly. We had done a trial run the day before. The dog was strong and didn’t listen well. I dreaded the task. “Right after school, you put him on the leash and walk him, then clip him back on the chain outside,” my father instructed, hanging the leash on a peg just inside the pantry door. “Hang the leash on the nail in the tree right above his dog house.” For this task, he would give me fifty cents each day when he came home from work.

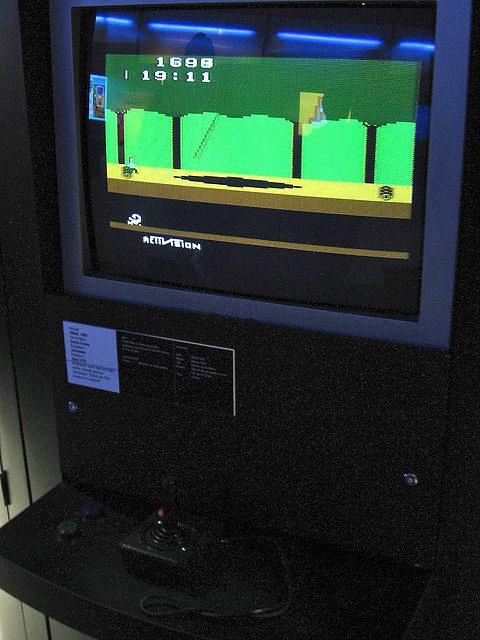

“Pitfall!”

The next day I came right home from school and promptly plopped myself in front of the TV to play our brand new Atari 2600 game, “Pitfall.” I gave nary a thought to the poor beast out in the yard. When my father came home for dinner, he found me in the living room furiously working the joystick and red button to hop over alligators and rattlesnakes, avoiding all the pitfalls in the game.

“Did you walk the dog?” he asked. In a split second of calculating, I realized he could not know if I had walked the dog or not. He hadn’t been home. “Yes,” I lied. Down went my electronic man into a miry bog.

“Good,” said my father, and plunked two quarters onto the video game console. “Keep up the good work.”

The little brown-haired man on the screen appeared for a second life.

With relief and delight, I realized . . . I had gotten away with it! I also felt a pang of pity for my dad, who I had not figured for a sucker. It rocked my world a bit to know that my 11-year-old self had outsmarted this man whom I had previously admired and respected (with just a twinge of fear).

Three more days this continued. By Thursday, I had advanced many levels in the Pitfall game. I learned to swing on ropes and avoid scorpions until I made it to the hidden treasure. When my father came home, I concocted believable stories about what Quasimodo and I had seen on our walks – how he had strained to get at a squirrel, or found some animal carcass and rolled in it. And every day the treasure appeared – two quarters on my game console. It was a sweet racket.

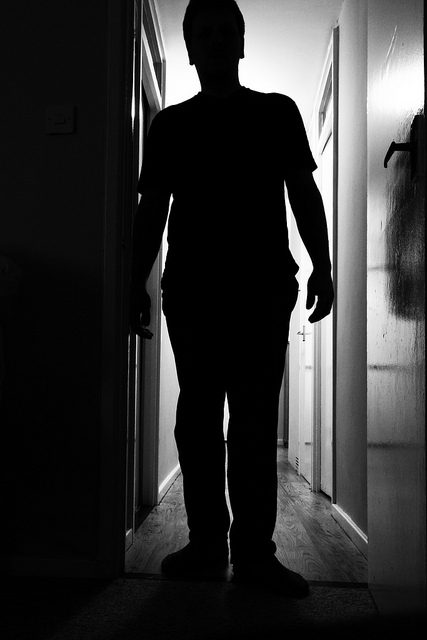

But on Friday evening my father came home later than usual. I was already in bed, tucked in, ready for a peaceful sleep. Just as I was ready to close my eyes, I heard his footsteps approaching my room. The door swung open and my father’s darkened figure loomed against the hallway light. I could not see his face. But somehow I knew . . . he knew.

My mind raced while my heart ran around my chest like that little brown-haired man running from rolling logs. How did he find out? Did someone tell him? How did he know?

My father’s silhouette stood there wordlessly as a hot lava mixture of panic, shame, and guilt shot through me and I burst into tears. What was he going to do? Spank me? Ground me for a week? The agony of anticipated punishment clawed at my brain.

Finally, he spoke, never moving from the doorframe, his voice deep and his words measured.

“You never took the leash off the hook in the pantry.”

All the air escaped my lungs as I realized my simple, stupid mistake. I saw the leash dangling from his hand in the shadow. With a rush of fresh tears and terror I gasped out more sobs, awaiting my sentence. Was he going to hit me with the leash?

“Don’t. You. EVER! Lie. To. Me. Again.”

No leash-whip was needed. Every word lashed my brain, my conscience, leaving a stinging mark.

“Don’t ever lie to anyone! You will always – eventually – get caught.”

The door closed and his footsteps faded down the hall. In the darkened room, tears slicked my hot cheeks. I couldn’t believe he didn’t punish me. But, then, he didn’t need to. I knew I had disappointed him. That was worse than any physical punishment for me.

Many years later – when I became a parent myself – I would come to call this a “teachable moment.” My father taught me that night that honesty trumps any mistake. This is not to say that I never told a lie since that fateful night. I’m a human being, imperfect, and sinful. But I learned a powerful lesson from that incident that has stuck with me all my life. The short-term consequences for a misdeed are nothing compared to the shame of a cover-up. Be honest and you’ll avoid the pitfall of lies that can suck you down like a little brown-haired man in quicksand.

Was it “entrapment”?

In a sense, yes. From the very first lie, my father knew what I was doing. We could say he set me up. He allowed me to continue telling lies night after night, knowing full well that I thought I was pulling a fast one on him.

But if I had just been honest from the start and admitted that I did not walk the dog that first night, the entrapment would not have been necessary. Would I have been punished for disobeying my father? Probably. And, of course, that’s what I feared and wanted to avoid. However, it took quite a while to regain my father’s trust and respect – which meant more to me in the long run. So I strove to be an honest kid from that point on.

“You shall know the truth, and the truth shall set you free.” (John 8:32)

In response to Flynn’s lawyers’ accusations of “entrapment,” Special Counsel Robert Mueller, who is charged with investigating Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections and related matters, made an important clarification. “The defendant chose to make false statements about his communications with the Russian ambassador weeks before the FBI interview, when he lied about that topic to the media, the incoming Vice President, and other members of the Presidential Transition Team,” he wrote in a statement. “When faced with the FBI’s question on January 24, 2017, during an interview that was voluntary and cordial, the defendant repeated the same false statements,” he continued. “The Court should reject the defendant’s attempt to minimize the seriousness of those false statements to the FBI.”

Now that I am a parent to a teenager and a pre-teen, it bothers me that people like Flynn and all the others in Individual 1’s orbit lie without any shame. Because it undermines my parenting. As a pastor, the people in this administration are also undermining my efforts to teach the 8th Commandment to Confirmation students (“You shall not bear false witness.”). The highest levels of government are supposed to model the highest levels of integrity. But now the foundations of honesty have crumbled into a pitfall of swampy alligators and scorpions. If the president gets away with lying, the students naturally question, why should it matter whether we tell the truth? This makes for a very awkward, but very important, teachable moment as well.

What bothers me even more are my fellow Christians – even pastors – who continue to defend Individual 1 and his cronies, even as the lies fly out of his mouth and pile up around him like putrid fish. These defenders point to Hillary’s emails. Or try to sweep it all away with the generalization, “All politicians lie.” To some extent, that is true. But the level of gaslighting, hypocrisy, manipulation, and cult-like cover-ups is beyond anything this country has ever experienced.

I wonder what it’s going to take to restore integrity to the public square?

I wonder, too, if Flynn and Individual 1 might imagine Robert Mueller as the silhouetted father in the doorway, leash dangling in his hand? I know I do.

Our country needs a teachable moment. We need to find a way out of this pitfall.

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary (Kentucky) and author of the book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015).

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary (Kentucky) and author of the book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/

Read also:

New Year’s Resolution: Bring Back the Taboos