It’s been 16 years since the start of the Iraq War. For the record – some Christian ministers preached against this war. We got strong push-back. But history bears the truth and necessity of our prophetic witness. This is the sermon I preached on March 23, 2003, just after the war began.

I have struggled for months as to whether I would support preemptive military strikes on Iraq.

I have tried to stay informed by all points of view, both for and against military action. I have read and listened to voices on both sides. I have talked and argued with people whom I respect, and those whose opinions I strongly disagree with. And I have changed my mind countless times. I have been on the fence, not able to make a decision, and have watched others more sure of their beliefs than me take action accordingly.

Then as I watched the so-called “countdown” on Tuesday night, I realized that my personal struggles had no bearing on what would actually happen. Perhaps, like me, you have felt that no matter your views, values, or beliefs, we are all being swept along on a tidal wave over which we have no control. I have felt disempowered, irrelevant, cynical and, yes, angry and worried over the whole affair.

When I feel this way, I have a tendency to want to avoid what’s going on. I disengage.

In fact, as late as Thursday, it had not even occurred to me that I should preach on this war. I had my sermon already prepared, and it did not mention the Iraq War in any way. I had felt so oversaturated with the whole thing that I wanted to just act as if it did not exist. It happened without me, what does it matter whether I address it or not?

But then Thursday afternoon I had lunch with the female clergy group I belong to here in Media, Pa. And the question came up how each of us was handling the Iraq War situation in our congregations and from our pulpits. I shared that our church is starting a prayer list for family members called into service, and that our senior pastor addressed the matter very directly in his upcoming newsletter article. I also said that our sanctuary would be open to everyone during office hours Monday-Friday for prayer and meditation. I said nothing about my hesistancy to address the war in my sermon.

But one of the other clergy women said that she would state very clearly what her beliefs are as a Christian.

“I oppose all war,” she said.

One of the other women challenged her, “You mean you don’t even believe in the ‘just war’ theory?” She shook her head, “There is no such thing as a ‘just war.’”

St. Louis Park, Minnesota. September 21, 2011. Photo credit: Fibonacci Blue. Creative Commons Attribution License.

This gave me pause, because I had always believed that some military action was allowable in certain circumstances. My thinking had aligned with the ELCA’s social statement, For Peace in God’s World (adopted in 1995), which states that war is permissible if it meets the following criteria:

The war must have a just cause. It must be waged by a legitimate authority. It must be formally declared. It must be fought with peaceful intention. It must be a last resort. There must be reasonable hope of success. And the means used must be proportional to the ends sought.

Now, personally, I leaned towards not supporting this Iraq War because it did not meet all the criteria for a just war. In our country, war must be declared by Congress. No such thing has been done. And I do not believe that we have exhausted every alternative for a peaceful resolution to the conflict. So this war is not a last resort.

But what this colleague of mine was saying was that, in fact, under no circumstances is war ever just. Similarly, there’s no such thing as “just rape”, or “just child abuse.” This got my wheels turning.

I decided to do some research on this term, “just war.”

I learned that the idea was developed by St. Augustine around the year 400 CE, who essentially said that there is sometimes a moral obligation to use violence if necessary to defend the innocent against evil. He came up with some of the basic criteria for a just war – which the ELCA Social Statement references.

But for the first few centuries after Christ’s ascension, Christian approaches to war were largely pacifistic in nature. Jesus never made a distinction between “just war” and “unjust” war. Jesus’ message was consistently one of nonviolence. “Those who live by the sword will die by the sword” (Matt. 26:52). There was never any justification for violence in the realm of God which Jesus preached and taught.

However, as soon as Constantine legalized Christianity in 313 CE, a shift happened.

The Roman Empire made Christianity the state religion in order to help secure its power. So grateful were Christians and their leaders not to be persecuted anymore, it became very easy to accommodate themselves to the dominant power in the world. Ever since that time, the Christian commitment to nonviolence has been compromised. The teachings of Jesus have been watered down to suit the interests of powerful individuals and leaders. And the kingdom of God has been shaped around the whims of whatever earthly kingdoms are fighting for power.

We may like to say that war can be justified when defending the innocent. But with the possible exception for WWII, I can think of no war conducted in the last two millennia that has completely met the criteria of the just war theory. The problem is that it is too easy to manipulate the criteria for a just war. There are too many ways to justify one’s own stance when trying to say that initiating military aggression is just.

President Bush made some promises in his speech earlier this week.

He promised that “the dangers to our country and the world will be overcome. We will pass through this time of peril and carry on the work of peace. We will defend our freedom. We will bring freedom to others. And we will prevail.”

However, what also needs to be said is that killing oppressive rulers, such as Saddam Hussein, still makes us killers. To quote the theologian, Walter Wink:

We want to believe in a final violence that will, this last time, eradicate evil and make future violence unnecessary. But the violence we use creates new evil, no matter how just the cause . . . Violence can never stop violence because its very success leads others to imitate it. Paradoxically, violence is most dangerous when it succeeds. (Engaging the Powers, Walter Wink, Augsburg Press, 1992, 216).

War is always failure.

War always promises more than it actually delivers. But choosing to act on a conviction of nonviolence is never a failure. Because even the smallest act of nonviolence is a way for God to work through it to bring peace into our world. Nonviolence never fails. Even when it is not successful, it still never fails. Because it offers a new way of resolving conflict that ensures life instead of threatening destruction.

Being a person of peace means that you refuse to resort to violence as a means to accomplish any objective. Actually, it challenges you to think more creatively, to find ingenious solutions to seemingly intractable problems.

What does this mean to me, personally, as a Christian?

It means that, for the first time, I am beginning to say with firm conviction that I am committed to nonviolence. I am no longer on the fence, trying to decide who’s right or who’s wrong in this particular military conflict. For me, it’s not about choosing sides anymore. It’s about choosing a third way. It’s about choosing the way of Jesus.

So, not only do I not endorse this war — I don’t endorse any war.

I realize that I take great risk in saying this, especially publicly, as a leader in a Christian church. And I know that my conviction will not magically resolve the overwhelming complexity of this world. I understand that sometimes we are forced to make difficult decisions about the violence done to us by others, and that nonviolent solutions are not always evident.

But my reason for sharing this with you – in the pulpit – is to let you know that as a pastor in the Christian church, I am engaging in this process of discernment.

I am not asking you to think the way I think. Instead, I am inviting you to do your own soul searching.

Engage this process not just as a citizen of the United States, but as a world citizen, and as a Christian. View this war, and all armed conflict, indeed all violence, not just from one side or the other. View it as a disciple of Christ.

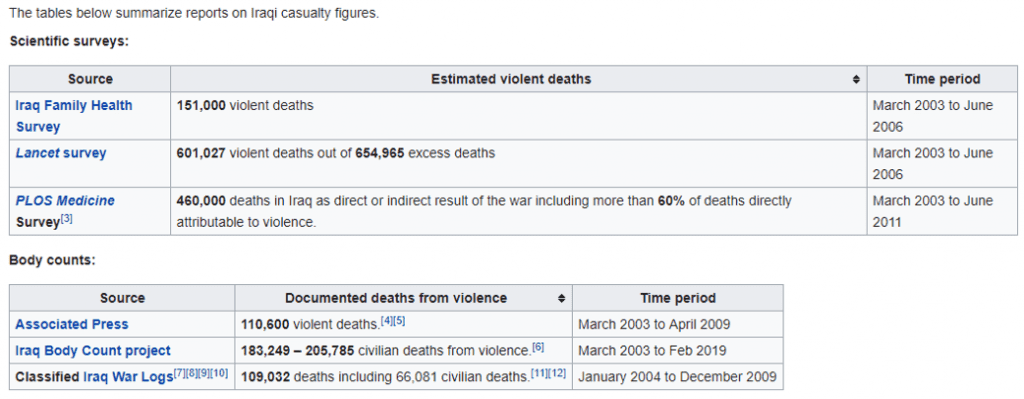

For example, a friend of mine pointed out to me that when you hear the casualty reports come in, you will hear them numbered according to “them and us.” But how does God see those numbers? God will not care if they are soldiers or civilians, American or Iraqi. God will only see God’s sons and daughters dead in a war. God will only mourn at the total number of dead — no matter whose side they are on. When you see those numbers come in, don’t just look at American casualties. Add up both sides. And mourn that number. Because they are all sons and daughters of God.

So, what can I do as a Christian citizen of the world who chooses to live in a country that has initiated aggression against another?

And whose military defends my very right to say these things in public? Understand that my critique is not against the women and men who have pledged their lives in defense of our country. They deserve honor and respect for their willingness to sacrifice.

But while this is an ongoing process of discernment for me, I do know one thing. I can start very small. I can pledge to my unborn child that I oppose violence in all its forms. I don’t know exactly how this will manifest itself. But I know that at the very least it begins with vision, where we can begin to see conflict without violence as an option.

This is, of course, a very personal decision.

There are many other Christians, including people in this church, people in other churches, and soldiers on the front lines of this conflict, who have gone through their own process of discernment and come to a different conclusion than me.

I know that there are people who will disagree with my conviction. But I am intentionally opening myself up to that. Because I believe that the Christian community is a place that can hold these different views in creative tension, allowing the Holy Spirit to work in and through them.

I accept that there will be consequences for my stance of nonviolence. But God promises that this is the way that leads to true life, uncompromised integrity, and actualized hope. To again quote Walter Wink:

The crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus are the assurance that there is a force at work in the world to transform even the most crushing defeat into divine victory. We are thus freed from having to produce results; we have only have to believe in what we cannot yet see. We are freed from despair; we only have to trust the One in and through and for whom all things exist. We are freed from having to succeed; we only have to be faithful (Wink pp. 218-219).

Each of us will have to make our own decisions when faced with these dilemmas.

But as Christians, we must be engaged in the process of discernment.

We must challenge each other to think through our convictions and actions. We must also continue to respect one another and to care for one another, despite our disagreements.

And we must trust God in a world where we are tempted to trust violence as the way to secure peace. God has made a promise to us, to the entire world, that nonviolence is the way to life. And God’s promises never fail.

Amen.

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary (Kentucky) and author of the book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015).

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary (Kentucky) and author of the book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/

Further reading:

How to Preach When You Are Afraid

Preaching Across Divides: Purple Zone Strategies for Pulpit and Public Square

How to be a Christian (and a Pastor) After the Midterm Elections