The story about the Slaughter of the Holy Innocents is not what we want to hear on the Sunday after Christmas. We like to hear about Mary and Joseph and the baby Jesus cuddling in the stable. We want humble shepherds and choirs of angels. We long for the image of the star illuminating Bethlehem in a halo of light.

But this story in Matthew 2:13-23 of Herod murdering all those baby boys in Bethlehem?

We would rather skip this one. We’d rather not talk about a brown-skinned refugee family fleeing from an enraged tyrant. We want to avert our eyes from the streets stained with the blood of helpless infants, their parents wailing inconsolably.

We would like to avoid this story, but here it is. It’s right smack in the middle of Christmas, right there in Matthew’s Nativity story. We can’t just ignore it, no matter how uncomfortable it makes us feel. So what do we do with it? How should we handle this story of violence and death?

How shall we approach this day that is known in the church as “The Slaughter of the Holy Innocents?”

It may help to have some background. First, we have to acknowledge that some scholars debate whether this mass murder actually happened. There is no historical record of the slaughter of the male children in Bethlehem at this particular time.

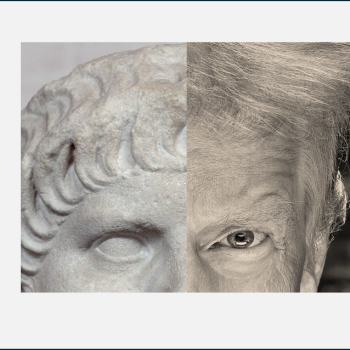

But it cannot be denied that Herod was a cruel ruler. He was an egomaniac known to be mentally unstable. A narcissistic psychopath, he was paranoid about anyone usurping his power and authority. In fact, the historian of that era, Flavius Josephus, recorded that Herod had his three sons killed so that they would not be a threat to his throne. Any man capable of killing his own offspring is certainly capable of ordering the murder of a town full of baby boys just to wipe out any potential threat to his power.

Whether this is an historical incident or not, however, the story of Herod killing these babies confronts us with difficult questions.

What is it like to live in a country where children can be murdered and there is no accountability?

What is it like to have a ruler who says he wants to worship the Christ, but then turns around and commits infanticide?

How can a country tolerate a leader who pretends to be pious, but whose policies result in the deaths of children?

There are also theological questions about this story that have plagued Christians for centuries.

Why do all these innocent children have to die just because Jesus is born?

Even more disturbing – why did God allow this slaughter to take place?

Which leads to the theodicy question: why does God allow evil to exist?

Some of these questions are bigger than we can handle in one sermon.

But there are important insights from this story of the Slaughter of the Holy Innocents that we need to understand.

One is that when Jesus comes into our world, things are going to get messy and violent and bloody. Do you know why? Because the powers of evil can respond to the love of God in no other way. Oppressive and violent leaders always react to threats against their power in the same way – through suppression, censorship, intimidation, and the use of weapons and violence.

Herod is only one in a long line of leaders and governments who have committed mass murder in order to protect their power.

He is no different from Hitler, Stalin, Pol Pot, white slave owners, the apartheid government in South Africa, Bashir al Assad, and the Taliban. Down through the ages, innumerable kings, governments, dictators and military regimes have singled out whole groups of people to be systematically oppressed and killed. We call it genocide. We saw it in the Nazi concentration camps. We saw it in the US government’s killing of the native peoples of North America. And today, seven children have already died in the concentration camps at the U.S./Mexico border. According genocidewatch.com, there are currently fourteen genocide alerts across the globe, from Africa to India to the Middle East.

This story of the Slaughter of the Holy Innocents presented to us here, in the Bible, in the life of Jesus, gives us a chance to understand the deeper significance of how God’s incarnation affects our world.

It gives us an opportunity to discern how this story affects our lives. And how it will affect those regimes of oppressive power. Because there is a key point to understand here: God created these powers to be good, not evil. Governments and structures of power are meant to protect the innocent, ensure the rights of those most vulnerable, and oversee an equitable distribution of goods and services to all its citizens.

But God also created human beings with free will. And the will of human beings is continually curved in on itself. Greed, self-centeredness, and lust for power and wealth are all symptoms of the deeper problem of human sin – the sin of wanting to be as powerful as God. And when that human sinfulness is writ large over entire systems of government, military, economic, and cultural institutions – coupled with individuals who are purely self-serving and insane with their own lust for power – the results are devastating to any of the innocents who get in the way.

But hear me, saints of God – this exercise of sin is not God’s fault.

This is how those individuals bent on evil and larger systems of evil have chosen to consolidate and exercise their power – especially when confronted with the goodness and innocence of God’s incarnation. Remember that just as those hundreds of children were struck down by the swords of Roman soldiers, Jesus, too, will be struck down by the whips of the Roman soldiers and hung on a cross by the order of rulers crazed for power.

We might wonder if Mary recalled the inconsolable grief of those mothers when she held her son at the foot of the cross.

“A voice was heard in Ramah, wailing and loud lamentation, Rachel weeping for her children; she refused to be consoled, because they are no more.”

Mary, a descendant of Rachel, may have wailed with loud lamentation as her son lay in her arms, just as the mothers did on the day Herod killed the babies of her friends.

And yet . . . this is not the end of the story. On Easter morning we see that the power of evil did not ultimately prevail over the will of God.

Herod eventually dies and retreats to the back pages of history. Every ruler who thinks he has won will learn that God always finds a way for God’s purposes to be accomplished. And every innocent person who suffers at the hand of rulers who seem invincible will discover that God not only suffers with them and allows his blood to be spilled with them, but will allow his resurrected life to flow through them as well.

God does not shy away from the merciless hatred of tyrants.

The story of this Slaughter of the Holy Innocents and the saving of one baby boy hearkens back to the story of Moses placed in a basket on the waters of the Nile River. They hid him with the hope of saving him from Pharaoh’s order for all male children in Israel to be killed. Later, Moses emerged from Egypt to lead his people out of slavery and oppression and into freedom, giving them the law of God in the process. In the same way, Jesus will also be brought out of Egypt once Herod has died and the threat to the boy’s life is gone. As a grown man, Jesus will also lead people to freedom – not just from oppressive rulers, but freedom from all forces that threaten us, even the power of death itself.

The echoes of Moses in Matthew’s Gospel are meant to demonstrate that God’s deliverance comes right into the midst of the bloodiest, deadliest times in history.

So, we tell this story of the Slaughter of the Innocents because it reminds us that we, as a people of God, need to ask some hard questions of ourselves, and of those who wield seemingly invincible power today.

This includes our own government, and our military, and every business to which we give our money. We need to ask them some hard questions, such as:

Is there anything they do that contributes to the slaughter of innocents today?

Do we silently stand by and sanction child labor, child slavery, just so we can wear trendy clothes and sneakers and buy cheap electronics?

Do we agree to trade with nations that are known violators of human rights, just so that we can sell them Pepsi and Big Macs?

Is our inaction on gun violence worth children being shot – and many dying – every day in the United States?

Is the death of innocent children in cages worth the supposed security we receive by separating immigrant and refugee families at the border?

These are difficult, uncomfortable questions. And they’re questions that most of us don’t want to hear in church. But the Bible already raises those questions for us. So we have a responsibility, as inheritors of God’s salvation through Jesus Christ, to have the courage to raise these questions in our world.

We are called to honor the memory of those innocent children whose lives were lost – and all the innocents throughout the ages. We have to say their names and remember that God did not intend for them to be collateral damage in a tyrant’s murderous campaign for power. We have to remember names like:

Darlyn Cristabel Cordova-Valle, age 10, from El Salvadore; Jakelin Caal Maquín, age 7, Felipe Gomez Alonzo,age 8, Juan de León Gutiérrez, 16, Wilmer Josué Ramírez Vásquez, 2½, Carlos Hernandez Vásquez, 16 – all from Guatemala.

All of them sought refuge here, just as Joseph, Mary and Jesus sought refuge in Egypt. But these children did not find safety when they arrived. They died during an intentionally cruel campaign to keep brown-skin families separated, caged, and away from our society.

We have to tell their story with boldness and repentance.

Better, we have to enable them to tell their own story, to bring their suffering to light. We have to be willing to hear the hard truth about the atrocities committed against them. We cannot allow their suffering and deaths to go unnoticed, to be ignored, overlooked, or silenced, just so we can preserve our comfort zones. Let’s be honest about the evil in this world and not be afraid to call it what it is. Let’s strive to vigilantly keep watch over those most vulnerable so that we can shine the light of God’s truth into their most fearful places.

This coming year, let’s see if we can find ways to do the work Jesus calls us to do – to address political and economic abuse and the tyranny that leads to the slaughter of the holy innocents.

For each person this work will take a different form.

Maybe it’s by learning about the efforts of Amnesty International, or Doctors without Borders, and joining them in their work of protecting and saving those most vulnerable. Maybe it will take the form of writing letters to government or economic leaders. Perhaps it will be through marching in protests.

Or maybe you’ll think more about how you spend your money – holding back from the products made by certain countries or companies that abuse human rights. Perhaps you’ll decide to run for political office informed by your values as a Christian. Or maybe you’ll join the Peace Corps or a missionary group to help in the most direct way. And then maybe you’ll come back and tell us first-hand the suffering you have seen and where the need is most severe.

These are just a few of the ways that God may be calling you to respond to the problem of evil in our world.

Instead of standing idly by, blithely ignoring the plight of the innocents, we can find a way to proclaim the Gospel to them, for them, with them. And yes, even for the oppressors. This Gospel proclaims in no uncertain terms that the politics of God, the kingdom of God, will prevail. This Gospel proclaims that all those held by the power of evil will be set free – from the baby suffering in her mother’s arms, all the way up to Herod held captive by his own sin. God’s power will redeem all. Christ’s death and resurrection will redeem all. Thanks be to God!

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky. She is the author of Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/