Netflix has just launched its third season of Cobra Kai, the sequel to the 80s Karate Kid films. In Episode Three, they give us one of the most realistic and redemptive scenes involving a Christian pastor that I’ve seen in pop culture in a long time.

[Spoiler alert: This article discusses Cobra Kai’s Seasons One and Two, and episode three of Season Three.]

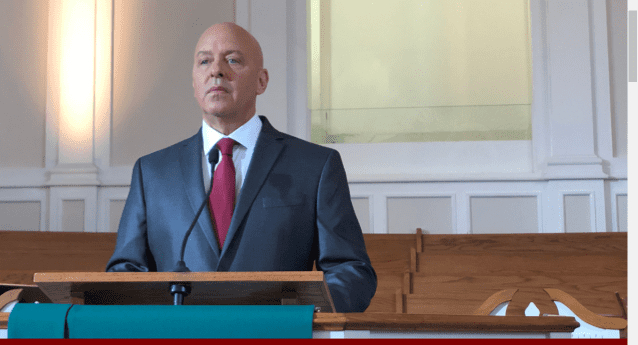

The pastor stands in the pulpit of a large Protestant church preaching about forgiveness. “Forgive me, Father, for I have sinned,” he says. He holds up a Bible. “This is where most of us go when we think about forgiveness, true?” The congregants nod. “But what about forgiveness in other forms? Forgiveness of others? And my personal favorite, forgiveness of thyself. This is probably our toughest battle. But listen, if God can forgive, then so can you.”

Just then, a drunken voice shouts out from the back of church, “Bullshit!”

The congregation gasps and turns to see an unshaven, ill-kempt man stagger up the aisle. “What about that time in Reno with those soccer moms at the Hyatt? Did God forgive any of us for that?”

The pastor pauses uncomfortably, then pushes ahead. “Yes, even that. Forgiveness is the core of Christianity.”

Swinging his paper-bagged bottle, the man scoffs, “I wouldn’t know about that. Not much of a churchgoer.”

The pastor apologizes to his congregants. “My friend is going through some hard times.”

“Nothing that I can’t handle,” the man slurs, lurching toward the chancel steps. The pastor steps down from the pulpit and the man turns to the congregation. “You know, this guy was a real badass back in the day. Fighting, drinking, partying.” He utters some unsavory remarks about priests and celibacy.

“How many times I gotta tell ya? I’m not a priest!” the pastor whispers. The drunken man presses on with his offensive language.

The pastor folds his hands in prayer and looks to the sky. “Forgive me, Father,” he says. “For what?” the man asks dumbly.

With a guttural cry, the pastor swivels and performs a sweep kick beneath the man’s feet, knocking him flat on his back. The congregation looks on in shock and surprised admiration. This was a side of their pastor they had obviously not seen before!

This is the opening scene of Episode Three, Season Three in Cobra Kai, the Netflix series that reboots the Karate Kid franchise from the 1980s. The drunken man is Johnny Lawrence (William Zabka) and the pastor is his old karate buddy from high school, Bobby (Ron Thomas).

In the next scene, they sit side-by-side on the chancel steps in the empty sanctuary, noshing on coffee cake. “How about we make a deal,” says Bobby. “You promise yourself to do positive things. Be a better person!”

Being a better person is exactly what Johnny has tried to do . . . and failed miserably.

Cobra Kai picks up the story of Johnny and his high school nemesis, Daniel LaRusso (Ralph Macchio) who famously defeated him in the first Karate Kid movie. Now in his fifties, Johnny is a gruff, old school, hard-drinking karate “badass” (his favorite word) who has revived the Cobra Kai dojo of his youth. In Season One, he leads his young charges to a victory at the All-Valley Karate competition, beating the sole student of Daniel who has himself revived the dojo of his beloved and now-deceased sensei, Mr. Miyagi (Pat Morita).

But in season two, the karate gangs take their sparring beyond the mat, viciously attacking each other in a brawl on the first day of school. The fighting ends with the All-Valley champ, Miguel Diaz (Xolo Maridueña), being kicked over a second-floor landing, slamming into a metal railing, and breaking his back. At the end of the episode, he is lying unconscious and paralyzed in the ICU.

Johnny is devastated. Miguel was his star student.

The boy whose kick sent Miguel flying is his estranged son, Robby Keene (Tanner Buchanan). By the end of season two, Johnny has lost his dojo to his sinister former sensei, John Kreese (Martin Kove). And his efforts to teach his students to make better choices than he did as a teen have ended in failure. Broken and inebriated, he seeks out his old friend and Cobra Kai buddy, now a pastor in a local church.

Cobra Kai is a surprisingly compelling series, despite its campiness and over-the-top drama that rivals daytime soap operas.

If you’re an 80s fan and have fond memories of the Karate Kid movies, the series is nostalgically satisfying. But it’s more than just a drive down memory lane in a gleaming yellow Ford Super Deluxe convertible. The Cobra Kai storyline is absorbing and unpredictable. The characters are morally complex. And the acting is believable, witty, and emotionally engaging.

Before the Cobra Kai series came out, I had introduced my two children, now teenagers, to the first three Karate Kid movies. They’re both martial arts students nearing their black belts, so they thrilled at watching Mr. Miyagi teach karate to Daniel, the underdog with a heart of gold. The first movie ends in triumph with a limping Daniel besting Johnny Lawrence with his one-legged crane-kick. However, we noted that the sequels did not live up to the first film. So we were dubious that the television series would be anything more than a feeble attempt to cash in on 80s wistfulness.

Yet Cobra Kai hooked us from the first episode.

Yes, the flashbacks to the early movies pluck our heartstrings. And, of course, there are plenty of action-packed martial arts battles to pump up the adrenaline. But what makes the show so absorbing is the way it wrestles with moral ambiguity, the complexity of its characters, and the interplay between them.

Cobra Kai dares to break the “happily ever after” formula by time-traveling us into a contemporary and unglamorous grown-up reality for its original characters. And it boldly veers from the hero-trope of the original films.

There are no “good guys” and “bad guys” in Cobra Kai.

Every character has a humanizing backstory that helps us understand their actions and how they end up where they do. The ruthless bully Hawk was himself bullied because of his facial scar. Merciless Tori is trying to care for her sick mother and younger brother while working and going to school. Even Creese, villain that he is, mourned his mother’s death as a teen, survived the Vietnam war, and ends up in a homeless shelter.

At the same time, Daniel’s boyish innocence and goodness in Karate Kid is neither preserved nor coddled in Cobra Kai. When we meet him in season one, he’s a gimmicky car salesman who has trouble connecting with his wife and kids. And as full-hearted as we feel seeing him return to karate and teach it to his daughter and her peers, we also see a man using these kids to work out his midlife crisis. And the results are tragic.

But it’s the complicated and oscillating relationship between Daniel and Johnny that is the emotional centerpiece of Cobra Kai.

Often the rivals find themselves unexpectedly bonding over their shared love of 80s culture and their devotion to their young students. They badger each other about their glory days and commiserate about growing older. Yet their bitter memories of the past, along with their dueling dojos and frequent misunderstandings, often repel them like same-poled magnets.

It’s Johnny – brusque, broke, and blitzed – who is the underdog in this series.

Unlike Daniel, there is no beautiful home, beautiful wife, beautiful children, or beautiful business to cushion Johnny’s fall at the end of season two. He is shattered, guilt-ridden, jobless, and alone. Which leads him to the church and Pastor Bobby.

We first re-meet Bobby in season two when the old Cobra Kai gang reunites to spring one of their buddies from the hospital where he is dying of cancer. We learn that Bobby, a thuggish fighter in Karate Kid, is now (of all things) a pastor. He has brought them together to give their friend one last motorcycle ride, one last drink, one final wild night.

What astonished me in season three was the way Cobra Kai portrayed this scene with a Christian pastor at a church. It wasn’t saccharine. It wasn’t superficial. And it wasn’t mocking, derogatory, or distorted, as is the case with many pop cultural portrayals of pastors. (See my review of First Reformed.)

When they’re alone on chancel steps after the worship service, Johnny expresses his despair.

“I put everything I had into my students. Taught ‘em how to be tough and show mercy. Thought I was doing the right thing.”

“You were,” Bobby assures him.

“Then why did all of this happen?” Johnny asks. “You want to punish me? Fine. But Robby and Miguel, they’re just kids.”

“I know,” says Bobby. “It isn’t fair. But you don’t do the right thing because it always works out. You do the right thing because it’s the right thing to do. Both of those kids need you. And you need to be there for them, whether it works out or not.”

I was impressed. This is what a pastor should say in a situation like this.

It wasn’t preachy or sanctimonious. He didn’t turn into a Bible-beating, gay-hating, science-denying Fundie. It was a moment of genuine pastoral care by a guy with an ignoble past who has tried to be a better man. And now he’s trying to help his buddy be a better man as well. It was a moment of redemption – both within the story, and for the portrayal of mainline Christian pastors in pop culture.

Even the show’s attention to detail was impressive. The paraments on the pulpit were liturgically correct! They were green for the season of Pentecost, which is exactly right for that time of year, late September. And when Bobby says he intends to have the church make a donation to help pay for Miguel’s surgery, he cautions that it won’t be as much as he’d like. “We’re still paying for our new roof.” Again, very realistic, as any pastor who has dealt with church building issues knows.

The episode ends with Pastor Bobby sitting with Johnny’s son, now in juvenile detention, and waiting for his father to arrive for his promised visit. But he never shows up.

Is Johnny off drinking again?

No. He’s at the hospital where Miguel is about to undergo surgery. The boy’s grandmother asks Johnny to stay. “I have to be somewhere,” Johnny demurs, knowing that his son is waiting. But she begs him not to leave. “Pray with us,” she says.

As with every episode, I can’t predict what will happen next in the series. But I hope Pastor Bobby has a recurring role. It’s refreshing to see a mainline Christian pastor portrayed accurately and realistically. Well . . except for that karate move during a worship service, of course.

Then again, maybe there was something more to that surprise move. The way I see it, sometimes God’s grace has to sweep-kick us to the floor and lay us out in order to get through. Redemption — like forgiveness — can come in many forms.

Want more pop culture through a religious lens? Try these:

Monsters and Saints: STRANGER THINGS Meets Daniel 7

The Healing Power of ‘Moonlight’: Race, Erotic Love, and Baptism

Like Tears in Rain: Rutger Hauer, Blade Runner, and Being Fully Human

Haunted by Goodness: Mister Rogers and the Love that Won’t Let Go

The Rev. Dr. Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and ordained in the ELCA. Dr. Schade does not speak for LTS or the ELCA; her opinions are her own. She is the author of Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is the co-editor of Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019). Her latest book, co-written with Jerry Sumney is Apocalypse When?: A Guide to Interpreting and Preaching Apocalyptic Texts (Wipf & Stock, 2020).

Leah is also co-founder of the Clergy Emergency League, a grassroots network of clergy that provides support, accountability, resources, and networking for clergy to prophetically minister in their congregations and the public square in this time of political upheaval, social unrest, and partisan division.

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/