In American Idolatry, Andrew L. Whitehead issues a warning about Christian nationalism informed by social science and his own journey out of fundamentalism.

American Idolatry: How Christian Nationalism Betrays the Gospel and Threatens the Church by Andrew L. Whitehead (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2023) is available from Baker Publishing Group in hardcover, as an ebook, and as an audiobook read by the author.

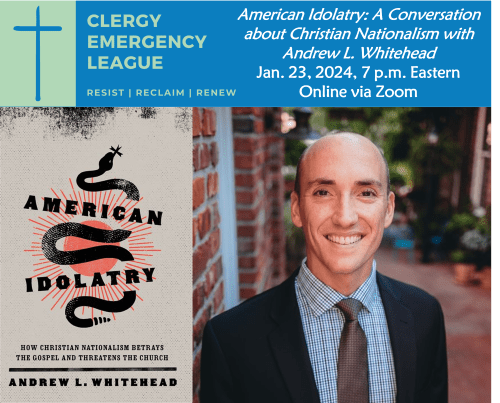

Andrew L. Whitehead: a social scientist with roots in fundamentalist Christianity

Andrew L. Whitehead, a social scientist specializing in religion and American culture at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, brings a unique perspective to the study of Christian nationalism because he was raised in the evangelical church. With an insider’s insight into the fusion of this branch of Christianity with the conservative political agenda in the U.S., Whitehead issues a compelling and undeniable warning about the threat of Christian nationalism. Not only does this movement hurt those affected by its violent and fascistic agenda, it is the exact opposite of what the church is called to be.

[Register for our CEL author chat with Dr. Whitehead onlin on Jan. 23 here.]

What is Christian nationalism?

Whitehead defines Christian nationalism as “a cultural framework asserting that all civic life in the United States should be organized according to a particular form of conservative Christianity” (xii). He traces the origin of American Christian nationalism to the emergence of a particular type of gospel taught in evangelical churches: a doxastic gospel. A term coined by philosopher Scott Coley, the doxastic gospel emphasizes belief in dogma at the expense of the practical gospel which focuses on practices such as “loving one’s neighbor, seeking justice for the oppressed, and caring for orphans and widows” (10).

Whitehead notes that American Christians “tend to ignore the practical aspect of the gospel, including justice for the oppressed” (12). They rationalize this by thinking that as long as they believe the correct dogma and encourage others to do the same, this is all that is required for their personal salvation.

Why do white Christians think this way?

As a white Christian himself, Whitehead surmises, “We already enjoy so much in the here and now. What use do those of us who are white American Christians have for overturning systems of oppression when we have long benefited from those very systems?” (12).

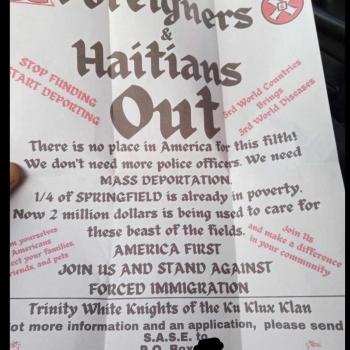

This privileging of the white experience and identity, combined with conservative political ideology leads to citizens who “demand and defend [their] own rights at the expense of others, not alongside them,” (48). Taken to its extreme, such attitudes lead to bullying, intimidation, stripping of rights, and violence. This is the consequence of American idolatry, and it is antithetical to the teachings of Christ.

[Have questions for Dr. Whitehead? Join our online CEL author chat Jan. 23! To register, click here.]

Christian nationalism and white identity

This kind of conservative Christianity has been shaped by white Christians who have used their religion to justify and rationalize the stealing of land, bodies, and labor for their power and enrichment. “It centers and privileges the white Christian experience because it essentially teaches that this country was founded by white, conservative Christian men for the benefit of white, conservative Christian citizens,” Whitehead explains (15).

It is this belief in the sanctity of white identity that is the quintessential American idolatry. And this idolatry finds expression in symbols of power, actions that instill fear, and violence that intends to secure compliance and submission with its authoritarian agenda.

Empirical data and personal journey

One of the things that makes Whitehead’s book so compelling is that he uses empirical, scholarly research and sociological data to explain how Christian Nationalism has taken hold in the U.S. But then he uses Scripture, theology, and his own religious journey out of conservative Christianity to show readers how to move toward a gospel-centered faith grounded in the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. In Whitehead’s assessment, “Christian nationalism makes American Christians less Christlike [and] betrays the gospel” (8). And he hopes this book will convince those Christians who sympathize with Christian nationalism to rethink their loyalties and their values.

After two chapters explaining the origins of Christian nationalism, Whitehead devotes the next five chapters to the means and ends of this movement: power, control, domination, fear, and violence. While substantiating his assertions with data and scholarly research, Whitehead’s primary aim in this book is to challenge Christian nationalist beliefs by invoking historical Christian teachings rooted in the Bible and the life of Jesus. The result is a book that is both solidly researched and compellingly argued.

Breaking through the Christian nationalist echo chamber

Many of the seminarians and pastors I work with have Christian nationalist sympathizers in their congregations. These church leaders wonder how to break through the echo chamber of propaganda and misinformation that has captured their fellow Christians’ logical reasoning and basic human compassion. For Whitehead, one of the things that made a difference for him were the mentors and friends who asked him pivotal questions.

For example, he recounted a conversation with a youth pastor who challenged his thinking about the righteousness of using violence to defend the U.S. Then several years later he talked with an Australian friend who questioned Christians rationalizing the killing innocent citizens in the war on Iraq. It wasn’t an immediate change for Whitehead, but more of an incremental shift over time away from the Christian nationalist metanarratives. This kind of shift is what pastors should pursue with patience, persistence, and prayerful conversation with their parishioners.

[Are you a pastor who would like more ideas for ministering with Christian nationalist sympathizers? Register for the online CEL author chat on Jan. 23rd here.]

Asking the questions, connecting the dots

Whitehead’s book shows what can happen when pastors ask pivotal questions of their Christian nationalist parishioners to make space for that shift to happen in their hearts and minds. At times it may seem that our sermons about God’s vision for justice are either blocked by closed hearts and minds or drowned out by the onslaught of nationalistic messaging. But what pastors and faith leaders can do is lay down the gospel “dots” with the hope that people will start to connect them.

Especially helpful are the stories Whitehead tells about people and churches that have taken steps to actively oppose, challenge, and counteract Christian Nationalism. These stories include a group of Christians collaborating with those outside of the church to advocate for freedom to practice religion – or not – without government interference. Another story is about a congregation that engaged in a courageous act of making reparations to the Black community. In each of these chapters, the examples he lifts up can spark ideas for any Christian congregation seeking to counter the political agenda of Christian nationalism.

Christian nationalism as theology

Whitehead states that Christian nationalism is not primarily a theology, but rather a philosophy and “cultural framework intent on privileging a conservative ethno-cultural and political orientation—one draped in religious rhetoric” (145). But after reading this book and others like it, I’m beginning to think that perhaps Christian nationalism is more of a theology than we might think.

I say this because theology makes claims about who God is and what God does. And there is no doubt that Christian Nationalism creates a matrix of divine characteristics that construct God in a particular way. This God is male, white, dominating, coercive, violent, and voracious in its appetite for the acquisition of souls, land, bodies, and unquestioning devotion.

Granted, one might say that Christian nationalists construct God in their own image, which is true. But such a construction results in a stark theology that determines the opinions, social media posts, voting patterns, and harmful behaviors of a significant portion of the U.S. population. Whitehead makes it abundantly clear that the theology of Christian Nationalism must be resisted, confronted, and countered by Christians at every turn and in every corner of the U.S.

How white Christian Americans can resist Christian nationalism

Whitehead insists that staying out of the political process is not an option for white Christian Americans. It’s not a matter of whether Christians should engage in social issues, but how. And he offers several suggestions, including defending religious liberty for all, leveraging our power to benefit those marginalized through our society, and showing empathy toward those who are different from us while also cultivating humility.

Most importantly, Whitehead encourages those engaged in the resistance against Christian nationalism not to give up hope. When taking these steps and taking these stands against American idolatry, we plant seeds that reshape the landscape and remake ourselves and our churches into the vision that Christ has for us. And this vision of love, grace, fairness, equity, and flourishing for all — no matter how those in power try to threaten and destroy it — will prevail.

The Clergy Emergency League will be hosting an author chat with Andrew L. Whitehead online on Jan. 23, 2024, 7:00 p.m. Eastern. Register here.

Read also:

Countering the Temptations of Christian Nationalism: Matthew 4:1-11

Palm Sunday and Countering the Violence of Christian Nationalism

It’s Okay to Be A Progressive Christian. Here’s Why.

Stay tuned for my follow-up piece: Is Your Pastor Preaching Christian Nationalism? Signs and Red Flags

How to learn more about the Clergy Emergency League:

CEL is a network of nearly 2,500 pastors throughout the U.S. who provide support, accountability, resources, and networking for clergy to prophetically minister in their congregations and the public square in this time of political upheaval, social unrest, and partisan division.

Visit the Clergy Emergency League Website.

If you’re a clergy person and would like to join our private FB Group, click here to request membership. If you join us, please make sure to answer ALL the questions (including agreeing to our group rules) in order to be welcomed as a member.

Our public Facebook Page is open to any and all persons who would like to follow the work of the Clergy Emergency League. Click here for our Facebook Page. Make sure to click the ‘Like’ button!

The Rev. Dr. Leah D. Schade is the Associate Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and ordained in the ELCA. She is the co-founder of the Clergy Emergency League. Dr. Schade does not speak for LTS or the ELCA; her opinions are her own. She is the author of Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is the co-editor of Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019). Her newest book is Introduction to Preaching: Scripture, Theology, and Sermon Preparation, co-authored with Jerry L. Sumney and Emily Askew (Rowman & Littlefield, 2023).