![The skyline of Richmond, BC, Canada taken from Aberdeen Station. - by Grotskiii, February 2013 (Richmond_BC_Skyline-1.jpg) (CC BY-SA 3.0 [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en]), via Wikimedia Commons](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/721/2014/08/Richmond_BC_Skyline-1.jpg)

In the summer of 2015, I moved back to Richmond, British Columbia. My wife was starting a job at a community pharmacy. I was furiously editing the book that became Theological Reflections on the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement.

This was a tricky task. On the one hand, some of the interested parties in the production of the book wanted it to be about Asian liberation theology. At a surface level, that made sense. The prodemocracy Umbrella Movement street occupations were, after all, protests, and nothing says liberation theology more than a protest. In fact, the theologian who wrote our foreword, Kwok Pui Lan, was one of the co-authors on the book Occupy Religion: Theology of the Multitude, where she and Joerg Rieger argued that the Occupy Wall Street protests were a sign that hierarchies in church and society were being invalidated by a global multitude’s demands for liberation. It seemed that this insight was a straightforward connection to Asian liberation theology, which is a thing. In the 1970s, illegal translations of Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed circulated in Korea during the Park Chung Hee capitalist dictatorship. Through critical conversation generated by the book, the people developed a minjung consciousness, a radical awareness that it was they, not the government, who were actors in history and could make a society of their own will. Around the same time, a visit from Pope Paul VI to Latin Catholics in Asia led to the emergence of the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conference (FABC). As my co-editor on the project Jonathan Tan has shown, a major hallmark of FABC’s style was to adopt the form of ‘basic ecclesial communities’ from Latin American ‘base communities.’ In these more intimate settings, people could be more participatory in the life of the Church and also generate new ways of working for justice in their societies, which included both an awareness of political economy and the interreligious reality of coexistence in Asia, in which Christians are a minority. Another form of Asian liberation theology was Dalit theology in the 1980s, in which Jesus is seen as identified with the Dalit caste in India and thus undermines the caste system altogether.

But as some of the contributors and I noted in the book, there were some problems with understanding the Umbrella Movement as a straightforward application of liberation theology. For one, there was the very obvious irony that the protests were directed against the People’s Republic of China. You could, of course, say that anything after the 1978 liberalization reforms is not your granddaddy’s communism, but even so, the historian Timothy Cheek has shown that in Chinese intellectual consciousness, there is still a kind of ‘living Maoism,’ the fantasy that Mao Zedong, the great figure of mass revolution to the point of inciting a revolt against his own government in 1967, is still somehow present in the world. In many ways, Mao was the global inspiration for liberation theology in the first place. Is it liberation theology when you protest Mao’s political descendants, however deviant their views and practices might be from the old man?

As the lead editor of the book, I struggled with this tension. Reading Asian liberation theology into the Umbrella Movement seemed to me to be an imposition. But it wasn’t not liberation theology either. One of the contributors, Sam Tsang, proposed in his essay that maybe the task of ‘liberation’ should be thought of through the insights of the literary scholar Edward Said. Instead of trying to read into the situation, perhaps what should be done is to read the world before the text, to truly understand the actual situation of oppression instead of imposing categories onto it. I quite liked this idea. Editing his essay was also a joy because he writes like Bruce Lee talks. Conversing with him led to the final form of the book, which had me navigating around the concepts of liberation theology while calling for an actual Hong Kong theology, a prayer to God that comes out of the actual situation of Hong Kong’s political structures denying its people political agency because of the city’s complex constitutional relationship with the mainland. Liberation theology is not a concept. It’s a praxis.

But in doing that, I began to think of my own situation. I am not from Hong Kong. You could say that I am ‘Asian American,’ but I had no consciousness until graduate school about how the term was associated with the Third World Liberation Front’s 1968 strike in the San Francisco Bay Area and its Maoist underpinnings. I am, of course, from the suburbs of the Bay Area, but I grew up in pretty conservative Chinese evangelical churches that pushed an ideology of Asian developmentalism onto us. Chinese evangelicalism in Fremont and Hayward were about the furthest thing from liberation theology imaginable.

Here I was, then, editing this book that navigates the Scylla and Charybdis of whether the Umbrella Movement was an expression of liberation theology, but I had just moved back to yet another suburb: Richmond, in Metro Vancouver. For me, Richmond has a bit of a mythological status. I was born there. My parents’ church did not do baby baptisms, so I was dedicated without water at the same church at which my dad later flamed out as a pastor. Six weeks later, we were on a plane to the Bay Area. Dad had an engineering job. Every so often, we would make the drive back up to Vancouver to see all of these people of legend from that church, where we were still ‘overseas members’ according to the directory. Their way of doing church was a lot more fun than the Taiwanese church in the Bay Area that was all about Chinese school. In Richmond, they watched McGee and Me, they had Charlie Brown Christmas, they went bowling at Aberdeen Centre before it became an Asian mall. I even had a godfather and a godmother in Richmond. Before my godfather died of cancer, he gave me a paintbrush. I still have it. There was also a street in Richmond called ‘Garden City.’ I liked the name of that because it sounded like Eden. I used to play-act in the living room wearing plastic Viking armor fighting the Philistines to defend Garden City and protect the pretty girls. When I was a child, Richmond was legend.

It is often said that cities are sites where the real and the imagined come together. Walter Benjamin and Henri Lefebvre had Paris. Edward Soja had Los Angeles. I was editing – which really meant that I was writing more than half – a book on Hong Kong. Suburbs, however, seldom get such praise. They’re often characterized as placeless, kitschy, without character. People who live in them must be like their bland landscape. Creativity and even liberation are to be found in cities. This is why I was so proud of myself for moving to Seattle for a postdoctoral fellowship. I had grown up in Fremont. I had done all of my higher education while living in Richmond. Now it was time to be a big boy and go to the city.

And then I was back in Richmond. The first time I had moved here was when I was eighteen. It was in the post-9/11 era, and there was lots of talk about war in the United States. I had the idea of moving back up, and my dad moved the whole family. Bit by bit, the fantasy of Richmond was taken apart. I had fought for the pretty girls, and the women rejected me. I had defended Garden City, and the church spit us out. I had imagined an idyllic lifestyle that was different from the model minority rat race I ran in the Bay Area, and we ended up in a Chinese ethnoburb. I got into a program in geography where people, including my supervisor, studied cities. They knew things about poverty, gentrification, aesthetics, transnational migration, and housing about which I had no concept. I wanted to be smart and sophisticated like that, but at the end of a day at the university – even after parties – I’d have to make the trek back to Richmond where I belonged. I resented that. By the time I moved away, the only fantasy of Richmond that I’d share was that Once Upon a Time had filmed where my wife and I had started dating, in the kitschy fishing village of Steveston on the western edge of the suburb. I called Richmond ‘Storybrooke‘ as a joke. Now I was the punchline.

I was scrolling through my Facebook news feed around this time, and I came across some people sharing an article celebrating the anniversary of The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill as still the greatest album ever made. I was intrigued. Lauryn Hill had been popular among my friends when I lived in Fremont. But I had internalized the idea that I should really only listen to classical music; at one point, even jazz was out of the pale (I even said to a trumpet teacher who told me to listen to Diana Krall that I didn’t want to, because of the sex). Because of this, I had never heard the Miseducation. But I had Spotify. The next time I decided to procrastinate on editing that Umbrella Movement book, I put on my headphones and pushed play.

A schoolbell rang. I did not expect that from a hip-hop album. Please respond when I call your name, the teacher says. He takes roll. Then he calls Lauryn’s name. No answer.

It’s funny how money change a situation. I had to turn down the volume. It was not music I was used to listening to. In fact, when I lived in Fremont, I didn’t even consider rap to be music. And yet, here I was listening. And then it wasn’t rap anymore. It was a ballad. It could all be so simple, but you’d rather play the game.

And then, a guitar. One day. You’ll understand. Zion. I put my hand to my ear. It was magic. Look at your career, they said. Lauryn, baby, use your head. But instead I chose to use my heart. Now the joy of my world is in Zion. I did not know that Zion was Lauryn’s son. I thought it was Jerusalem. And she was marching towards it. I sat up straight when they starting chanting that. Beautiful, beautiful Zion.

At that point, I was transfixed. I don’t even remember much more of what I heard for a bit. It just washed over me. Then: every ghetto, every city, and suburban place I’ve been, make me recall my name in the New Jerusalem. I sat up again. Is that what she sang? Every ghetto. Every city. And suburban place I’ve been? This woman has no shame.

And then, the piano ballad. My world, it moves so fast today. The past, it seems so far away. And life squeezes so tight that I can’t breathe. And every time I try to be what someone else thought of me. So caught up, I wasn’t able to achieve. Damn straight. That’s why I had a writer’s block. That’s why I was procrastinating. But deep in my heart, the answer it was in me. And I made up my mind to define my own destiny.

And then, theology: I look at my environment and wonder where the fire went, what happened to everything we used to be? I hear so many cry for help, searching outside of themselves. Now I know his strength is within me. And deep in my heart, the answer, it was in me. And I made up my mind to define my own destiny.

I sat there stunned. I was transfixed. Then I hit play and listened to the whole thing again. When it ended, I did it again.

From there, I went on a black woman blues and ballad binge. I knew that Angela Davis had written a book on this, but now I was going to hear it all. My tastes were not as refined as Davis’s, though. I had And I am telling you on repeat, both the Jennifer Holliday and Jennifer Hudson versions. That led to the Whitney Houston version, another person I had not cared to listen to. That led to a Whitney Houston binge, which led to a Mariah Carey binge. I started hearing their voices while chanting at the Eastern Catholic temple. I was not ok.

The Jesuit who became my spiritual father, whom I had met during the Umbrella Movement, pulled me back from the crazy just in time. I asked him for spiritual direction because I had trouble writing, and I really wanted to leave evangelicalism. I thought that he would work through everything that was going on in my mind and get me to a place where I could think clearly. But my spiritual father, as I’ve mentioned, is a materialist. He specializes in parsing out fantasy from reality. I wanted to talk about what was going on inside my head. He wanted to talk about what was going on. It was like pulling teeth. Miraculously, after insulting a realignment Anglican bishop online for inviting unqualified and downright racist speakers to speak on the second generation in Chinese churches and being called out for it by a Chinese Baptist, I ran to this Eastern Jesuit materialist to get a new bishop, an Eastern Catholic one. He thought it was all still going on in my head, but took me in anyway. Soon after, I wrote an insane post about how Anglicanism is like Orthodoxy and will get back together with Rome eventually. Most of my readers loved that piece because, in the words of an expert on Arab Orthodoxy who read it, it was ‘zany and madcappy.’ That means it was stupid and all going on in the realm of my own fantasyland.

It is hard to live in reality. Fantasy is a remarkable motivator. It can make you crazy, but another word for that is creativity. It is what gives life to cities. For me, it gave magic to suburbs. It is the dream that keeps the model minority alive. It is the therapy by which evangelicalism is sustained. It was what drove the writing of my dissertation, as I traversed the familiar sites of my youth in Fremont and Richmond – and the looming figure of Hong Kong behind it all – armed with the power of Radical Orthodoxy.

But what we don’t know when we are in fantasy is that it is also oppression. A fantasy is not life lived in a place. It’s the formation of an imaginary colony on top of a place. As Michel de Certeau argues, the way that people live, therefore, is usually an affront to fantasy. You expect the world to work a certain way in your dreams, but life outside your head is not the same as what you imagine. In the final analysis, this is what made me and the other contributors so uneasy about imposing liberation theology onto an analysis of the Umbrella Movement. Most of the people on the streets in Hong Kong weren’t out there because of an ideology. They were just there to defend the other protesters and to assert their primal feeling that Hong Kong is their home. When I wanted to talk about evangelicals, my spiritual father asked me about my marriage. When I wanted to talk about ideas, he questioned whether I was actually doing any writing. Systematically, he revealed to me that I spent a lot of time living inside my own head. As I looked around the academy and the rest of the world, for that matter, it seemed that a lot of people were also doing the same thing.

The oppression of fantasy in contemporary society, I came to learn, is what The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill is mostly about. Coming off my faux womanist music high, I began to make myself listen to the Miseducation once a day. I wanted to hear what Lauryn was saying. I wanted to get past it washing over me. I wanted to slow down and listen.

As I listened, I read. I learned that Lauryn had grown up in a suburb in New Jersey. In high school, she was part of a band that eventually became the Fugees. She had a career not only with them, but also in the movie business. She was wildly successful, and along with that came a wild and crazy sex life with her bandmate Wyclef Jean. It could be said that she was living the dream of a model minority.

And then, she woke up. You might be forgiven if you think that Lauryn must have woken up after the Miseducation was done being wildly successful in its own right. But that’s not how things went down. What happened is that Lauryn got pregnant, and people advised her to get an abortion for the sake of her budding career. She didn’t only refuse. She let the creative energy of Zion in her body fuel her poetry. The album became a family work. People say that her lack of productivity after the Miseducation, as well as her prison time for unpaid taxes, her propensity to be late for shows, and even her being sued now by her trombonist for back wages, is a sign that she burned out. I don’t see it that way. What I see instead is that she’s done being the model minority. She’s just a person, and persons screw things up.

I started saying that Lauryn was our generation’s greatest theologian. Of course I was exaggerating because I was still sorting out my own relationship to fantasy. But I think I am starting to have a better idea of what I was trying to say. The liberation theology of yesteryear does feel outdated because even in the occupy protests of the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street, Maidan, and the Umbrella and Sunflower Movements, it doesn’t feel like it’s the masses who have been conscientized going up against a colonizing capitalist dictatorship. As far as I can see, contemporary social movements from the street occupations to far-right nationalisms to Black Lives Matter and Idle No More are just outpourings of anger into streets. They don’t have demands because there is no message. It’s just that they are tired of being figures in someone else’s fantasy. But they fantasize plenty themselves too, which is how they usually fail.

But a theology that liberates, as far as Lauryn Hill is concerned, is precisely about the fantasy of oppression, the dreams that miseducate. These are imaginations that are powered by ‘that thing, that thing, that thing’: sexual desire gone out of control that gloms onto bodies, money, and institutional power all at the same time. You are trapped because you are an agent in someone else’s perverse fantasy. Worse, you are encumbered by the desire of an institution that is not even a person. That makes sense, Ivan Illich says, because those institutions are ungirded by what he calls a Promethean myth. Prometheus stole fire from the gods and rejected Pandora’s gift of just being in the world. The story goes that Prometheus was then punished by the gods by being chained to a rock. This is a metaphor, Illich says. The truth is that the machines and institutions made by Promethean fire will chain you to them and make you their slaves.

Break down that fictive world, Lauryn says, and see what you have. Every ghetto, every city, and suburban place I’ve been, make me recall my name in the New Jerusalem. Out of the fantasy, I have two feet on the ground. I am in a place. I have a family. I have a home. The people around me are the ones I care about. They care about me too. You can call this configuration a ‘community,’ but that’s much too sociological. It transcends blood, race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, age, and even religion. It’s simply the people who are around me in my everyday life. It doesn’t matter if I’m in a ghetto, a city, a suburb, or even an ethnoburb. It’s just love, concretely so.

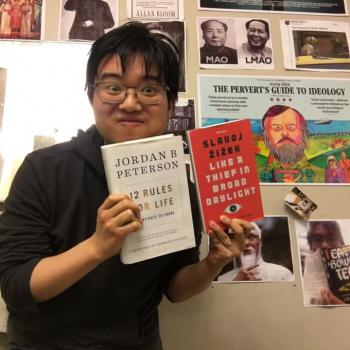

We need to censor our dreams, Slavoj Žižek declares. No wonder he, like Lauryn, has been talking a lot about love lately. When you become liberated from fantasy, then you are not just studying the practice of everyday life. You are, in what de Certeau intended all along, practicing everyday life.

This insight brings me back to how I started writing about Chinese Christians in the first place. I was in my junior year in high school, and I was struggling with the concept of the model minority. The teacher put James Baldwin’s Fire Next Time on our desks and told us to read it. I did not understand it, but she made us write a poem. I wrote on the Chinese church and how its ideological attachment to being Chinese prevented it from accepting a young pastor’s kid’s budding romance with a non-Chinese person. It was based on how Baldwin found that the communities that he encountered for black liberation – whether the black church or the Nation of Islam or Black Power – were more attached to the concepts of blackness and whiteness than to persons. Baldwin’s basic argument was that the suppression of the truly erotic power of personhood would lead to an all-out racial apocalypse. The task at hand was to channel that eros into love across race in society, difficult as that might be (as he shows in Another Country). Doing this work had to happen at an everyday level. It begins with love for the persons around you.

It turns out that the seeds of my conversion lay all the way back at the beginning of the journey. But failing to understand the relationship between fantasy and reality, I had been seduced by every shiny thing that lay in my path. And deep in my heart, the answer, it was in me. And I made up my mind to define my own destiny.

Is this still liberation theology? I don’t know anymore. I am influenced by Freire and Fanon and Illich, but this is going further. My spiritual father and I are materalists insofar as we find that the material is constituted by grace. I have become so suspicious of fantasy that it makes up most of my confessions. The first time I made my confession, it took me four hours. During the rite of chrismation, my spiritual father put his epitrakhil over my head and absolved me before the presence of the entire congregation. Richmond is not a mythological place for me anymore. It’s where the Lord had mercy on me while I was living in my own fantasies and set me free.

I sometimes think about how this has changed my writing. I often wonder how it has morphed my prayer life. I reflect a lot on my intellectual journey. And then I catch myself. I have to live.