Perhaps the scariest thing for a young scholar is to revisit the dissertation. It is also a necessity, as it is the source of our publications and future books, but among the struggles I’ve had with the piece is that in addition to the academic work, it was a deeply personal labor of love too. In fact, I think that not enough love went into it because the intellectual paralysis that resulted from it, with a trajectory from Occupy Central and the Umbrella Movement into my conversion to Eastern Catholicism and my doubling down on an investment in Asian American studies, was a reckoning. I had succeeded in writing about Cantonese-speaking Protestants, I thought, in a dispassionate, distant way, denying my identification with them in any way and offering an assessment of their secularity as a kind of third party. In the revisions that are coming in my book manuscript and articles going into the pipeline, the data remains the same, but I feel like I am more honest about it, that what constitutes my findings are not so much about Cantonese Protestants as if they were a community to be observed but rather me trying to articulate the various ways that they see the world from the perspective of their communities. The material was gathered in love; it can only be presented with love.

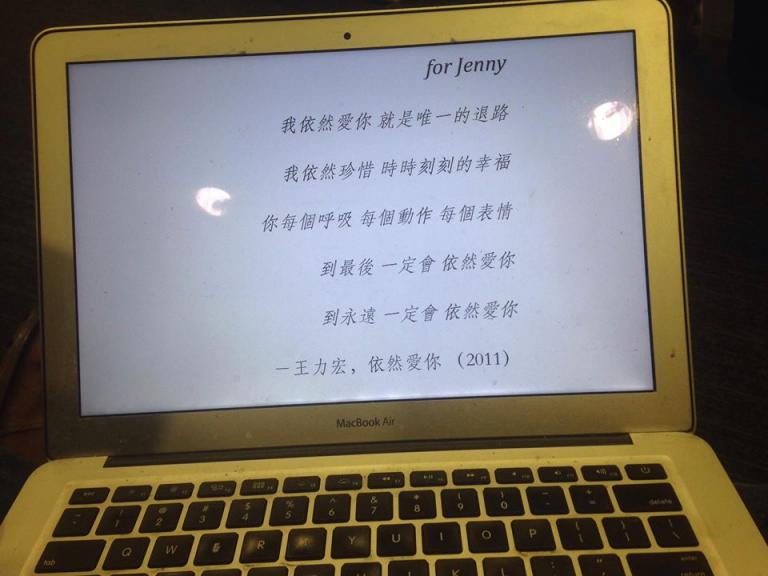

In reading back over what I had written, I came across the dedication page. I had dedicated the dissertation to my wife Jenny, with words from the Mandopop singer Wang Leehom. The year that Jenny and I were engaged, Leehom (as he is affectionately known) collaborated with the Asian American film company Wong Fu Productions to produce a new song that he had written to be included as a value-added purchase in a greatest hits album. Probably both an homage to his fans and to the person he has come to call his beloved (my understanding is that he’s married with three kids), the song is titled 依然愛你 (yiran aini), or ‘Still Love You.’ The lyrics to the chorus, which I reproduced in full at the front of the dissertation, roughly translate:

I still love you, which is the only back way

I still cherish each hour and moment of treasured fortune

Your every exhalation, every move you make, every emotional expression

At the end definitely I will still be loving you.

It might seem an odd choice to place a song in Mandarin at the front of a dissertation on Cantonese Protestants, and I think it says more about me than it does about Jenny. My heart works on two tracks, both Cantonese from my family and Mandarin from the Taiwanese church at which I grew up, and feels the spiritual in both languages before I begin to express what I am feeling in English, which is a language I learned when I was in the midst of my third year of existence, about two years into learning how to talk. I am unable to count how many times I’ve revealed myself to be an utter sap while listening obsessively to the Cantopop queen Sammi Cheng’s Mandarin song about the word ‘love,’ with passages taken from both the thirteenth chapter of the Holy Apostle Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians and the translated wedding vows from the Book of Common Prayer. When I’m in Richmond, I really don’t care whether the Chinese reading from the Apostol is in Cantonese or Mandarin; I hear both, which are usually read by women at our temple, as the gentle voice of an older sister speaking into my soul.

I look back at why I dedicated the dissertation to my wife, apart from it just being a nice thing for a husband to do. In the acknowledgements, I speak about Jenny being the embodiment of how to contemplate and enjoy everyday life, the foundation of building a home together. This sensibility is completely natural to her; it is not so for me. I have been schooled in the work of fantasy, of dreaming about how to advance in the world and move through and between institutions as a way of securing a future. I even considered the doctorate in such model minority terms at first, thinking of it as positioning me above the community I was studying while professing to be among them. Jenny has no such pretensions. There has never been a sense for her that her education made her somehow better than people or that it means that she has to advance in institutions that take her away from her people. In fact, she is a community pharmacist, and good at it. I’ve watched her interact with older people with zero medical knowledge. Her eyes light up when they finally get it about their health.

The joke between us is that Jenny is smarter than me because I had to get a PhD, do a postdoc, and seek employment as an academic to realize that everyday lives matter. Of course, the most frequent complaint is that for Cantonese Protestants, everyday lives are all that matter, with zero structural analysis even of vectors by which they themselves experience oppression, much less other groups that they complain about. Sun Yatsen called this phenomenon the sheet of scattered sand, the recognition that most Chinese people only seem to care about their families and clans instead of abstract concepts like nationalism, democracy, and socialist welfare. In fact, those three things were what Sun spent his life trying to get Chinese people to care about, even founding a nation for them in 1911. It still can be said that history will be the judge of his success. Most Chinese people only really care about who they love, who they hate, and what they are eating.

I used to disdain this way of living, and I even felt like my academic career was a source of tension with my family and my communities. I even ran to Eastern Catholicism to get away from it all, which is hilarious because it is Eastern Catholic mystagogy that is getting me to integrate instead of feeling like I’m living in two simultaneous worlds. The truth is that the world from the perspective of such communities is full of love, passion even that is even more intense when it is purified from the passions. Just ask Yang Guo from Jin Yong’s ‘passion book’ The Divine Condor Heroic Couple. Not only do his intense emotions earn him the name ‘West Crazy’ by the end of the book, but also his love is purified as it becomes intensified by his attachment to the Little Dragon Maiden and her absences from his life. After they get married, they are even separated for sixteen years. That is, as one friend put it, ‘a long time to wait for bae,’ but the point is that there is a beauty to how the Cantonese Protestants I write about experience the world. For all of their hangups about sex and their insecurity about private securitization and their misunderstandings of democratic and socialist political theory, there is a love in their families and their food.

A friend of mine told me when I was stuck in my revisions that what I had to do in my scholarship is to taste that living water – indeed, to drink of it and never thirst again, but to even have it flow out of me. I pondered what that meant, especially as it comes in the encounter of the Lord with the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well. Living water is an encounter of love; it is the flow and the stillness that characterizes my spirituality too. To say that ‘I still love you’ in relation to the dissertation is to discover through my everyday life – my spiritual praxis in the Kyivan Church, my marriage, the people who still make up our familial communities – is to realize that that living water flows through my scholarship too, that the writing and the publishing and the teaching and the being an intellectual is as much part of this love in everyday life as anything else. It is not to be disintegrated from the quotidian. In fact, the everyday is an intellectual space. It is also where my writing is situated.

A final thought is that I realize that the book that I am writing and my blogging are beginning to diverge in their convergence here. The academic writing really is now going to be about the Cantonese Protestants, clear into the Umbrella Movement and the comparative aspects that that engenders. But I’m going to need this blog for a little while yet. I too have my own everyday life, and I want to write about it. It is wrapped up with Cantonese Protestants, but if I were to make them about me, it would compromise the project. Where they converge is where they divide, and I am excited to see what this integrated acceptance that scholarship and reflection are two different but related projects will take me next.