Today, we received my friend Faith by chrismation into our Eastern Catholic church. She took as her patron saint the same Faith whose prayers I invoke daily from the Holy Martyrs Sophia and her daughters Faith, Hope, and Love, the same person those named Vera also take for their patron saint.

Faith is from China. I knew my spiritual father would take the opportunity to tell of his encounter with Chinese Christianity when he traveled there, and he did. Like me, my spiritual father is Chinese, but born in Canada. For us, China is a place about which we have heard stories as children and where we dream of traveling.

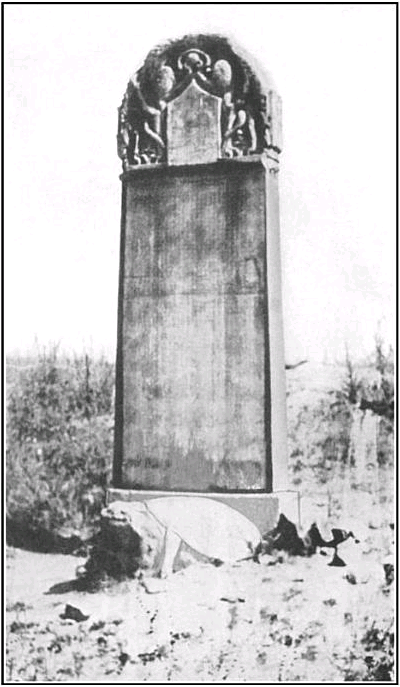

Our spiritual father – me and Faith’s and everybody else’s who has been received into Eastern Catholicism by his hand – used his homily to talk about his journey to see the stele that the Syriac missionaries from the eighth century put up there. Many people, he reflected, would want to see the big tourist attractions like the Great Wall and the terracotta warriors, the latter of which is (like the stele) in Xi’an. He wanted to see the stele.

Faith is not from Xi’an, at least not that I know of, although the family of my Asian American writer friend Grace Yu in the Kyivan Psychoanalysis Study Group is. I don’t want to steal Grace’s thunder for writing about Xi’an because she has a lot of profound things to say about the place and will one day probably present them in such a creative way that I cannot begin to imagine yet. But like many of my friends from China, Grace tells me that her idea of Chinese food is not the normative Cantonese stuff that most people know because of the way that Chinese people migrated to the Americas in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For Grace, Chinese food is Xi’an food – pork burgers, lamb noodles, biangbiang mian.

In the same way, the epicenter of my spiritual father’s imagination of China is also Xi’an, though not for the food. During the Tang Dynasty, Syriac missionaries established such a stronghold of Christian churches within the empire that it was a metropolia – there was a metropolitan bishop, which meant that there were lots of bishops, which meant that there were lots of dioceses. Xi’an is the centre of that imaginary because there is a stele there, a pillar that details the story of how Christianity – the jingjiao, the Luminous Teaching – arrived in the land of the Tang and even includes some Aramaic as a tribute to the Syriac missionaries like Alopen who brought the teaching there. That stele is what my spiritual father wanted to see, and he told the story of being driven by two monastics to a hill where he saw its replica and then the real thing in a museum. He realized also that the pagoda nearby was not a religious temple; it was a library that held the relevant documents describing this phenomenon.

The church in China is a church of martyrs, which I think is why it is so appropriate that Faith chose one of the greatest martyrs from the earliest days of Christianity to be her patron saint. The reason that everyone seems to think that Christianity is a western religion in China is because few know that the Luminous Teaching was the work of the missionaries of the Church of the East. This is not common knowledge because Christian structures have often been seen as political, expedient to one imperial regime and threatening to another. By the time the Franciscans got there during Mongol occupation in the thirteenth century and then the Jesuits during the Ming Dynasty in the sixteenth, the work of the Church of the East had largely been forgotten. The stele had to be excavated, and then after that it proved controversial because what if this had been erected by the Nestorian heretics who had been condemned at the Third Ecumenical Council?

But martyrdom is not a matter of canonicity, and my spiritual father put it to us that Faith was coming into our church of martyrs, the Kyivan Church, from a church of martyrs. Indeed, if one really gets to know the Holy Martyrs of China during the Boxer Rebellion, one might discover that any kind of Orthodox superiority is overrated. Latins and Protestants were killed too. The martyrdom of the church of Alopen – the Luminious Teaching that seemed to have disappeared since the Tang Dynasty – resonates with theirs, as it does with all those persecuted and betrayed in China because neither empire nor state can countenance an alternate authority to its power.

Against such overcompensating regimes, Chinese Christians, whose lives are lived at the level of the everyday, offer the way of the heart. At the end of the service, Faith described in a public testimony her own journey into our church. She had been moved to initial Christian conversion through personal encounters with Christian people in the academy. She had found the Lord in a profound experience of crisis. She sensed spiritual movements in her heart after her conversion, and the journey to investigate what those were led her to study spiritual theology in Vancouver. It was from there that she discovered our tiny temple in the suburb of Richmond, and she came to the least attended service, the All-Night Vigil on Saturday nights, where she began to understand that worship involves the whole body, which brings the intellect into the stillness of the heart. She said that she told her Protestant friends that it was here that she truly met the Father who is G-d. They told her that they were happy for her, that she had found her home.

Faith’s journey, like my spiritual father’s and Grace’s to Xi’an, traces a pathway of heart. It is about feelings, discernment, profound experiences, and bodily involvement. This view of Chineseness runs quite contrary to the racist perception that Chinese people are asexual and don’t do emotions well, and Eastern Catholicism – as I said this morning – has a funny way of making you more you than before you got in. If one is Chinese, one really becomes Chinese, not in some orientalist sense, but – like I told Grace a few weeks ago – in the sense of having emotions gush from the heart and overflow into social engagements that constantly flub the boundaries of who is involved in one’s family.

To be family, to be home, is not biological if you are a real Chinese person. The home is the table under the roof where the people living together gather, and those people are your family, and you do right by them because your heart is open to them. The Chinese word for happy is open heart. One might say that there is nothing particularly Chinese about this sensibility, and I think most Chinese people would agree. In fact, most of us might say that it is not that those who cannot understand this heartfelt sense of the world are not Chinese – it is that their status as real persons is under great suspicion. This kind of thing is what Sam Rocha calls folk phenomenology, the encounter of the world from the perspective of ordinary people. The words, like our emphasis on the heart, are Chinese, attempts to use language to plumb the depths of a reality that is universal.

Today, the exquisite joy we feel stems from our hearts having been opened by receiving Faith into our family. She came in by the seal of the gift of the Holy Spirit, the chrism oil that marks the light that has shone in her heart, the source of the feelings that started her journey of spiritual investigation in the first place. If the offering of the Chinese church can be articulated in words, is it not that we bring to the Body of Christ the capacity for such deep emotion as the organizational principle of the spiritual life and our ecclesial sociality? Is not the drama of liturgy necessary for people like us because it is through the ritual that our deepest longings, desires, and overflowing hearts are channeled into the joy of being together? Is this not the open-hearted happiness that Faith spoke of in her testimony when she described how in this house she has met the Father and is now home? Does not Faith’s experience of our church demonstrate that a society can be organized according to the principles of the heart? Does not the brightness of such reflections suggest that we, an Eastern church that is not nearly as far east as the Syriacs, are also bearers of the Luminous Teaching, the jingjiao?

One more reflection: the words that I use for the world may be Cantonese – which is probably better described not just as the southern Chinese language of Guangdong Province, but likely the imperial language of the Tang Dynasty into which the Luminous Teaching was brought – but the larger truth is that I grew up with calling people uncles and aunties in my church family who mostly spoke Mandarin. Many of them were from Taiwan. From them, I learned the faith, not just in teaching, but in songs and actions and food and the sharing of testimonies that would be described as gandong, a term that, if translated as emotionally moving, doesn’t even begin to capture the depth of feeling that is being conveyed. The uncles and aunties I knew laughed loudly and cried often; they made food that was hot and music that was hotter. Rightly so, my Cantonese friends who, like me, see it as an imperative to defend Hong Kong and its Cantonese street culture from authoritarian colonization from up north have seen the imposition of Mandarin as a language there and in the diaspora as a kind of colonizing exercise by the Chinese government. But the language known as Mandarin to some and the ‘ordinary language’ (putonghua) to others is just the longtime northern tongue that grasps at an attempt from ordinary folks to organize a society from the openness of the heart.

Mistakenly, when I was a child and much more insecure in my manhood than I am now, I mistook the heavily emotionally inflected timbre of Mandarin as a feminine language. My mother, who is Cantonese but studied Chinese language and literature in college, taught both languages to me as a kid, and my heart and its faith is formed according to both linguistic tracks. But the reason that my Mandarin is not as good as my Cantonese, though I should know both equally well, was because at one point, as a child, I stopped speaking it for fear of not being a real man. Real men, I foolishly thought at the time, could keep their emotions in check and didn’t have to cry all the time, unlike all the uncles and aunties who were so gandong.

Along with Cantonese, Eastern Catholicism gave me back Mandarin as the other language of the heart. Depending on who is there at Sunday liturgy, the Apostol reading is usually read twice, once in English and another time in a Chinese language. Some readers are more competent in Cantonese, others in Mandarin. Both speak to my heart in ways that English cannot; in fact, I have taken to ignoring the English one and really concentrating on whichever Chinese language I am hearing. The feelings of hearing both languages are of course different, and when I hear Mandarin, which is usually read by women in our temple for some reason (it is probably because we don’t have men who are competent in Mandarin), it is like hearing my mother, or an auntie, or a big sister speaking the Word of God directly to my heart. Today it happened again. After being received by chrismation, Faith stood at the ambo and read the Apostol in Mandarin. And again my heart opened, and I was very moved, very gandong, as if I were a little brother hearing a big sister speaking luminous words of life – the jingjiao – into the very depths of my being.