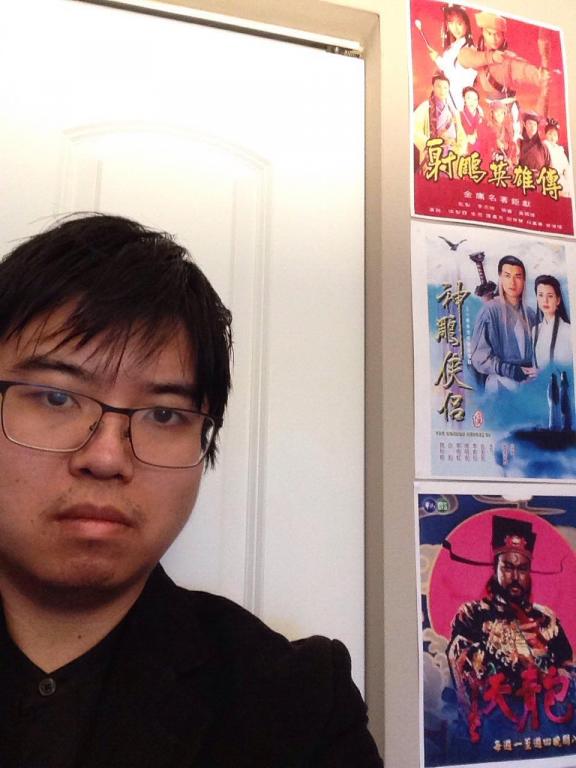

It was funny. My biological clock has been a little off because of a recent trip I took to a conference (it was very much worth it), and having trouble sleeping, I spent some of the earlier nights of this week searching on YouTube for a Cantonese television series I used to watch when I was nine. It was Hong Kong TVB’s 1994 drama series 射雕英雄傳 (Cantonese, sehdiu yinghong zhuen; Mandarin, shediao yingxiong zhuan), The Legend of the Condor Heroes (or better, The Saga of the Eagle-Shooting Hero). Earlier this year, I placed the posters from that series, its sequel The Return of the Condor Heroes, and an unrelated but still prominent drama Justice Pao (the classic stories of an uncorrupted magistrate) at the foot of my bed, at the door of my closet. That is how close these tales and their characters are to my heart.

Revisiting it was quite a review. The familiar characters of Guo Jing, the slow-witted hero, and his shrewd and kind girlfriend Huang Rong had shaped my understanding from an early age of what dating might look like, much more so than the more famous couple Yang Guo and the Little Dragon Girl in the sequel that I did not get to watch all the way through because of the sex (I grew up evangelical; even Grease was a bridge too far), and far more than the cheap courtship substitutes later introduced to me in evangelicalism as I Kissed Dating Goodbye. But even more than romance, I found myself appreciating with a much finer eye the way the characters interact with the larger historical story of colonization of the Song by the Jurchens and the Mongols, as well as how significant it is that if the characters are not fighting for love and honour, they’re dueling to gain mastery over books like the Nine Yin Manual and General Yue Fei’s Martial Strategy Book. I also relived my appreciation for the hilarious characters like the foodie beggar master Seven Grandpa Hong 洪七公 and the Old Childish Zhou Botong 老頑童, especially the eating, farting, and peeing scenes.

My spiritual father tells me that the Cantonese always have a way of justifying what they are doing as work, and I being no different decided to justify my trip down memory lane by thinking about it in terms of my first book, which is about Cantonese Protestants and their engagement with postsecular Pacific publics. It has struck me over the years how much the sensibilities of the folks I study cannot be solely engaged through the literatures criticizing the secularization thesis, or even through what is available by way of theorizing Chinese Americans. When I found the work of Frank Chin and his emphasis on the martial dimension of Chinese and Japanese literary cultures, it had brought me back to the stories I had learned as a child, including watching the Condor Heroes on television, but also stories my grandfather told me from the Chinese classics Three Kingdoms and Journey to the West. It was at an interesting time for me in Chinese school, when we were just getting advanced enough to learn the ‘four-word proverbs’ and the basic stories of the classics, that I began to become interested in both the modern stories of Bruce Lee (because of which I took Taekwondo – long story), the television series dramas like the Condor Heroes, and the Wong Fei Hung movies I watched at my uncle’s house, which I saw without connecting the dots to my dad being a Hung Kuen master and therefore within that martial tradition himself – and myself too, since I have learned the basic form of the tradition 工字伏虎拳, Taming the Tiger Fist with the Word ‘Work’.

I looked up the author of the Condor Heroes series, Louis Cha, who pen name was Kam Yong in Cantonese and Jin Yong in Mandarin (金庸). To my great surprise, I learned that the moment I had gotten the idea to rewatch the Condor Heroes, he had died. I did a triple take. I am not one to talk about the visitation of spirits with death, and I would never presume that even if that were to happen, Cha’s spirit would visit a nobody like me. Still, the coincidence was uncanny, and I have been sitting with it for the past few days. Indeed, I tried to write about it on that day, but these days, I do not seem to be able to bring myself to shoot from the hip, especially when I know that the results of such writing will be shallow and over-enthusiastic, reminiscent of my evangelical days when the words extreme and ultimate ruled the lexicon.

Tributes have poured in to honour Cha’s legacy. I like some of them, while others I do not. I appreciate the constant reminder, for example, that Cha was one of the founders of the Chinese newspaper Ming Pao, a generally reliable newspaper in the world of Chinese journalism about the state of the world. Others are more propaganda. There have been reminders over the last few days that the Chinese leaders Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin were fans of Cha’s work (never mind that there were rumors that he was supposed to be assassinated in the Cultural Revolution preceding the era of post-1978 Reform China), and the South China Morning Post attributes the conservative idea of a gradual transition to democracy in Hong Kong through a corporatist Election Committee – the very thing protested by the Umbrella Movement occupations later on – to Cha. Indeed, that same article quotes a number of pro-establishment Hong Kong and mainland Chinese figures, like Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, John Tsang, and Jack Ma of Alibaba fame. It does not mention that Cha quit from the Basic Law drafting committee after the horrors of Tiananmen.

I am not saying that I have to read every Chinese folk hero as supporting the Umbrella Movement, much as I would like them to, but I would have imagined Cha’s stance to be incredibly complicated. It has taken me this long into this post to say that the genre in which Jin Yong wrote was wuxia 武俠, which does not translate kung fu 功夫 (which just means ‘skill’), but martial hero. The world that Jin Yong wrote about may have been ‘China,’ but like the Chinese classics, reducing it to national coherence or order and stability is only something that a white orientalist whose knowledge of Chineseness comes solely from books and not everyday life can dream up. Jin Yong once said that those whose lives are not rooted in Chinese culture will not understand his work. He is right, but not in a cultural nationalistic sense that implies that you have to be ethnic Chinese or that you have to buy into an ideology of the nation or that you have to have been to China to get it. He is saying that you have to toss out your a priori understandings of China as a western fantasy first before you can live with ordinary people on the streets.

Like the other Chinese classical tales, Jin Yong’s Condor Heroes is set in a time of imperial turmoil. Those who have assumptions about what Confucian order is and how it has made China stable first thousands of years should already be put to confusion at this point. The saying goes, the embellished opening of the Three Kingdoms (not Jin Yong – the actual Ming classic) begins, the kingdom divided unites, united divides. Governments, bureaucracies, imperial rule, nations – these come and go and come back again, usually depending on whether they are corrupt or not, but what is real are the common folk, the everyday people and their heroes. Like the classics, Jin Yong’s works are about that world of heroes; indeed, it can be said that the Condor Heroes series is about what it means to be a hero. Kingdoms may attempt to rule the people, and to the extent that they serve the people under heaven, they are legitimate. But the heroes roam a world that is described in wuxia stories as the ‘river and lake’ (江湖, jianghu in Mandarin, gongwu in Cantonese) and the ‘martial forest’ (武林, wulin in Mandarin, molum in Cantonese). There, they have their schools of thought, their competitions, their quests for greatness and vengeance, their own styles of corruption and those who oppose the corrupt and fight for righteousness and justice. But the gongwu is not another world. The heroes are mixed in among the common folk, the monasteries, and even the officials of the kingdom, usually as crouching tigers and hidden dragons, as the saying goes – hiding their talents in ordinary life until they are called upon to put them to use. Corruption is framed as oppression; true righteousness and glory comes from defending the weak and doing right by those among whom one lives and loves.

I imagine that Jin Yong would not have had a straightforward answer about the Umbrella Movement. The movement indeed protested against the corruption of the nation and Hong Kong as a special administrative region. But it was revealed in the thick of the drama that the secret societies were also allied with the government, and it is not easy to equate the gongwu with the protesters, though claims were made to that effect and certainly the ethics of justice is drawn from the molum. Indeed, gongwu has in the modern world been what the secret societies of organized crime have been called. The term is tricky, and it can be corrupted as much as kingdoms might be, maybe even more so.

What Jin Yong might have had a clearer answer about, though, is the question of colonization. This theme is strong within the Condor Heroes, a time when the Song kingdom is so weak that they are driven south by the Jurchens who found a northern Jin Dynasty, even while the Mongols under Genghis Khan are gathering strength even further north. The politics of the heroes are not straightforward at all. While the main characters, the sworn brothers Guo Jing and Yang Kang, are Han Chinese and ought to have ethnic allegiance to the Song, the corruption of a local Song official by a lustful Jurchen prince divides them at birth, sending Guo to the Mongols and Yang to the Jin, where they both rise to positions of prominence within the court.

The difference of character between Guo and Yang is what is expressed in the novel. Though Guo becomes the heir of the Khan, he is also a bit stupid when it comes to learning things, but the denseness belies a purity of heart, and unable to bring himself to seek glory at the expense of those he loves, he becomes a defender of the weak. Yang, however, is raised to be the crown prince of the Jurchens, only to discover that it was all a lie, that his adopted father had ordered a raid on his home village to kill his birth father and marry his mother, and that he is really just a commoner. Yang struggles between falling in love with a common heroine Mu Nianci who wants him to live an ordinary life with her and his lust for power in the Jin court; eventually, after these sensibilities result in the deaths of many characters, he himself meets his end in an ironic but just way.

The everyday life of the gongwu, in other words, intersects at all levels of society, from the common folk to the highest echelons of colonizing and corrupt power. It is terribly interesting that Jin Yong wrote his novels from that very place too, as a critic of the Nationalist government in China before its fall, an exile to the British colony of Hong Kong because of the communists, a reluctant political figure in the confusing time of post-reform China and the handover of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty. Substitute the Nationalists, the Communists, and the British for the Song, the Jurchens, and the Mongols, and the setting for the story still works. It is why I don’t know what Cha must have thought about recent Hong Kong politics, but it is also a little irrelevant. The hero may be involved in politics, but real heroism is about the practice of everyday life. It is to live by the personal codes of justice to one’s family, the way of the heart in falling in love and building a home in an ordinary place, revenge against those who might do harm to those under one’s roof, heroism in using one’s scholarly and martial skills to defend the weak in usually quiet and unseen ways. Kingdoms break up families; the longing of the hero is to be together with one’s beloved, passing through life in the passionate hiddenness of a love that is not only translated the way that white people know it as ai (愛), but qing 情.

These are the stories that shaped my boyhood. Jin Yong is often called the ‘Tolkien of Chinese culture,’ and I am sure that readers in a Catholic public whose every other quotation is if not from the Inklings, then from Chesterton, would be pleased to hear it. But I encountered the works of Jin Yong before Lewis and Tolkien, just like my mother before me stayed up reading the Condor Heroes when she was eleven until her Methodist headmistress godmother forcibly took them away from her. She tells me she is thankful to have been saved from obsession, but I know my mom better than that: the Condor Heroes is rooted deep in her heart, and like flicking a switch, she will be right back there talking about the stories with me and watching them on television while I was a kid. Lewis had to invent new worlds as analogies to a modern secular one, and Tolkien theorized everyday life as there and back again in relation to the Shire. But the gongwu is not a separate space; it is the present, threaded throughout all levels of society, where one works out whether one is going to be ethical in knowing that one’s place is always with the common folk or unjust in participating in their oppression while seeking one’s glory.

In telling these stories of adventure and romance, Jin Yong’s central point is that being a true hero is about working through the passion of love. Far from the perception of Chinese people as asexual – most notably in Roman Polanski’s Chinatown – the characters of Guo Jing and Huang Rong, Yang Guo and the Little Dragon Girl, are the avatars of what it means to build a home on a romantic basis. Filial piety, the honor of brotherhood, the love by which marriages are built and families are made – if one understands such concepts as legal and dispassionate, one will have missed the point of Jin Yong’s novels, and indeed of Chineseness altogether. Indeed, the sequel to the series I love so much, The Return of the Condor Heroes 神雕俠侶 (which is better translated Condor Gods and Chivalrous Couple), has been called Jin Yong’s qingshu 情書, his ‘passion book,’ a novel that gushes with emotion and flows with feeling. The romance of Jin Yong is that homes and communities, societies and kingdoms, are built from the bottom up with such passionate love, requiring the cleanness of the heart that is found in Guo Jing, the literary cleverness of Huang Rong, the purifying journeys of Yang Guo, and the quiet solitude of the Little Dragon Girl.

Is this not then what I found in Eastern Catholicism? Is not the way of the heart and the building of a home on the romance of the hero the same call as the Ukrainian phrase that was spoken on the Maidan at the funeral of the Heavenly Hundred, heroes never die? Does this not mean that Jin Yong, far from being a Chinese cultural nationalist, describes a universal folk phenomenology, to borrow from Sam Rocha, that understands that everyday life is erotic? For such reasons, on the week of Jin Yong’s passing into the land of the ancestors, I honour him. I would have very little understanding of what it means to be a person without him. But because of his stories, I am reminded constantly that heroes are not famous, greatness is found in ordinariness, romance is the foundation of the home, and the skills I learn are for serving the communities that I love.