One of the pleasures of being on two calendars at the same time — the New in Richmond, the Old in Chicago — is that there are some points in the church year where I get celebrations twice. The time around Nativity and Theophany is one such point. I go home for the holidays when my fall quarter ends in early December, and I’m back in early January when my winter term begins. As it was, I got two celebrations of Nativity this year. The first I cantored in Richmond. The second I had to do as a reader’s service in my icon corner on the morning after I got back because my first day of classes was also that day. While our Bishop Benedict of Chicago reminds us that the calendars will not save us, he also tells us to pray in our families and parishes, to center the practice of prayer in what we do as church. My practices are thus undertaken in obedience to him.

I found the exercise very interesting, even enjoyable. With it, I have gotten to revisit the feast that I always feel is a bit rushed in practice in terms of the church calendar. I heard somewhere that if you look at the way that the calendar is designed around Nativity, it is almost as if it’s an afterthought, which makes sense because the truly ancient feast around this period is Theophany. There is a fast – St Philip’s – but really, there are only two weeks of liturgical preparation for the Nativity, the Sunday of the Ancestors and the Sunday of the Fathers.

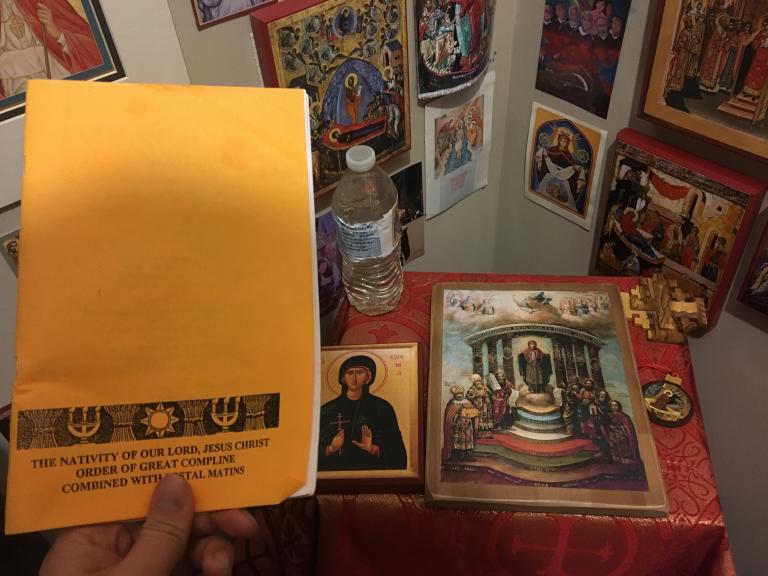

As it is, being on two calendars gives me a bit more traction to get into Nativity before it suddenly creeps up on me and is over, almost like how the Jesuit exercise of the examen is designed for a person to revisit their day and to savor that which was rushed over the course of one having to live it in the moment. I felt that keenly this year as I arrived back in Chicago on the Feast of the Great-Martyr Eugenia of Rome and then in light of the sudden devotion I felt toward her on the New Calendar, I was able to contemplate these graces all over again as I revisited the Nativity Compline and Matins services in the domestic space of the icon corner.

Nativity, as I’ve hinted before, is a very important feast to me. At my chrismation, the sisters and brothers at my temple purchased for me a small, portable triptych of the Nativity that I used to like to take with me. It is now in Richmond with my family, but I now carry it around as my phone’s wallpaper. When I used to pray the rosary, I really liked dwelling on the Nativity scene, reminding myself that what is happening in this mystery is that the Lord is born among us and challenges the powers that be. I used to like to ask Mary what she was thinking as I contemplated this moment at the manger. As it is, I recently told my friend that I have been shaped by the spirituality of the Nativity, to which she kindly replied that she didn’t really know what it meant to have a spirituality in this sense. I often use such moments as times of reflection to see if I can explain the tangled phrases that I use in simpler ways, and I tried to say that what it means is to pray with this picture in my mind. I don’t think what I said was satisfactory, but it kept me thinking.

Perhaps the greatest shock of entering the Kyivan Church when it comes to Nativity is indeed to find that the great feast to be celebrated at this time is Theophany. What is more, without the Latin emphases on the Christmas Mass and the tradition of Western carols — all beautiful, to be sure, and liturgies and songs I’ve enjoyed over the years — what I encounter now in our church is our own tradition. There is a Nativity meal, there are the services especially of Nativity Compline and Matins, there are the preparatory weeks leading up to the Nativity and the celebrations that follow it and lead up to Theophany.

What struck me this year was how closely the progression toward Nativity hews to the progression of the Matins canon. The last third of the canon, Odes VII, VIII, and IX, come after the singing of the Kondak hymn and concern, like the Sundays of the Ancestors and the Fathers before Nativity, the Three Holy Youths who refused to bow to the Babylonian king’s golden image and moves from there to the Theotokos herself as the fulfillment of this witness. Perhaps my thinking has been directed to this part of the liturgy because we have been praying against Chinese authoritarianism in Richmond, especially with the Moleben in Time of War Against Adversaries That are Attacking Us, which also prominently features the story of the Three Holy Youths. My spiritual father reminded us that those words that the Three Holy Youths said, Even if not, with reference to their assertion that God would protect them, became an anti-fascist battle cry in the Second World War, a refusal to capitulate to Nazism even if it meant that they would be blitzed and annihilated.

And so it goes for those whose days we celebrate before and after the Nativity. The Holy Great-Martyr Eugenia of Rome, for example, pretended to be a man and made her way to become a hegumen in the monastery, and even in the moment of death refused to capitulate to the empire. The Holy Martyr Anysia at Thessalonica, whom we celebrate today, spat in the face of her persecutor. Even if not became not for them, and yet they persevered to the end against imperial demands for them to forsake the Lord their God and turn to the worship of false gods, that which the theologian Karl Barth calls the no-gods that claim to rule the earth but are, as the psalmist says, but mortals — or as the Holy Prophet Isaiah mocks them, but wood and stone.

The fulfillment of all of this witness is in the Most Holy Theotokos. The mystery, as the irmos of the final ode of the Nativity Canon has it, is: Heaven – the cave; the Cherubic Throne – the Virgin; the manger – the place where Christ lay, the uncontainable God whom we magnify in song. The mysteriousness of the scene of the Nativity is that in this small space, the powers of the earth are shaken because it is a microcosm of the truth of the politics that underwrites the world’s existence. At the throne of the Theotokos whose womb is more spacious than the heavens, we worship the Child who is the Creator of the universe.

This, I submit, is the spirituality of the Nativity, the fulfillment of the Even if not of the holy martyrs who glimpsed the truth of the mysterious political order that undergirds the world and did not bow to those who pretended to be gods. It is, we might say, a theological politics, and the beauty of the Byzantine practice is that instead of having to be reminded that what those in the West perceive as a scene of innocence is actually a political one, the politics is embedded into our liturgies around Nativity — and indeed, in our weekly anticipation of the Resurrection as it is placed into the Matins canon. And like the progression of Matins, as the canon finishes, we might think that the service is done, only to find that this climax at the Nativity is not the end at all. The Service of the Praises then begins, culminating in the Great Doxology and the final Tropar of the Resurrection. Is this not our experience at Nativity, when all the build-up of St Philip’s Fast and the Sundays preceding Nativity build us up to the Feast, only to find Theophany, the truly Great Feast of this season, waiting just around the corner?