On this Feast of the Holy Hierarchs Athanasius and Cyril of Alexandria, I wanted to share a passage from Rowan Williams’s Arius: Heresy and Tradition that has stuck with me since I read it in the fall of 2008. At that time, I had just gone through a full-scale theological meltdown, having been confirmed as an Anglican on what I now know is the Feast of the Presentation earlier that February. Before the summer of 2008, I was a New Calvinist: it hit all the right notes for me as a theological system of divine sovereignty, combined with proper gender roles that felt nuanced enough for a single guy (which is to say, not very), and plenty of room for the charismatic. After that summer, I was not: enough had fallen apart in my discernment about ordained ministry that I wasn’t even sure what I believed about God anymore.

New Calvinism, I suppose, was compatible with the kind of Anglicanism I fell in with, which was the realignment of North American groups with the ‘Global South’ over sexuality issues. Of course, what that meant was that I was among people who made a hobby of mounting character assassinations of the Archbishop of Canterbury at the time, Rowan Williams. It thus surprised me when I was taking a theology course in the fall of 2008 in a frantic search to put myself back together spiritually that I began working on a paper on Arius and why anyone even cared at the time that he was a heretic. By this, one will know that I definitely have a New Calvinist background; among New Calvinists, the word heresy gets deployed like Clint Eastwood shooting from the hip.

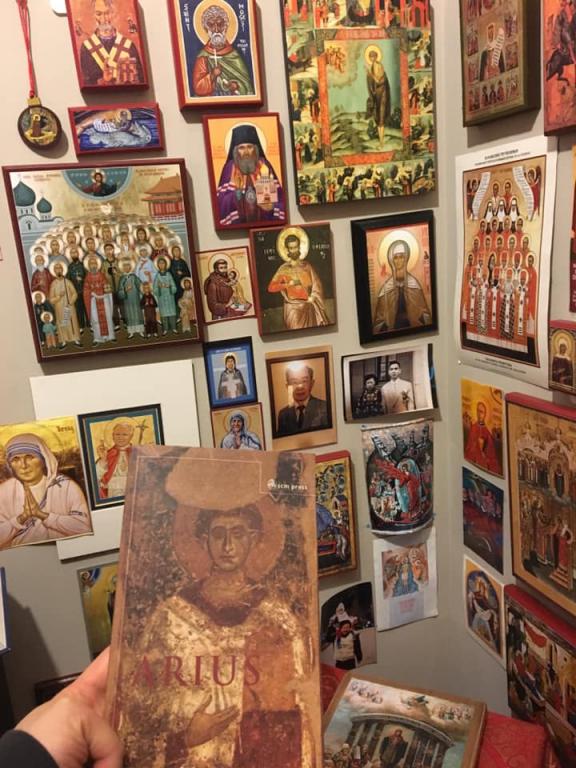

As I did research on this paper, I came across what most have called Williams’s finest work, Arius: Heresy and Tradition. To be honest, most of it was too technical for me. But that didn’t stop me from going wow when I realized that Williams was calling Arius a theological conservative for trying to protect God the Father from the suffering of the Son, as well as to defend early Christian formulations that the Alexandrians and the Byzantines were in their own right creatively developing. Orthodoxy, Williams argued, was creative and generative; heresy is conservative, a betrayal of the tradition by attempting to stultify it. The passage that spoke to me most was at the end:

But Athanasius and the consistent Nicenes actually accept Arius’ challenge, and agree with the need for conceptual innovation: for them the issue is whether new formulations can be found which do justice not only to the requirements of intellectual clarity but to the whiteness of the worshipping and reflecting experience of the Church. The doctrinal debate of the fourth century is thus in considerable measure about how the Church is to become intellectually self-aware and to move from a ‘theology of repetition’ to something more exploratory and constructive. Athanasius’ task is to show how the break in continuity generally felt to be involved in the credal homoousios is a necessary moment in the deeper understanding and securing of tradition; more yet, it is to persuade Christians that strict adherence to archaic and ‘neutral’ terms alone is in fact a potential betrayal of the historic faith. The Church’s theology begins in the language of worship, which rightly conserves metaphors and titles that are both ancient and ambiguous; but it does not stop there. The openness, the ‘impropriety,’ the play of liturgical imagery is anchored to a specific set of commitments as to the limits and defining conditions within which the believing life is lived, and the metaphorical or narrative beginnings of theological reflection necessarily generate new attempts to characterize those defining conditions. (Williams, pp. 235-6).

On this commemoration of the Holy Hierarchs Athanasius and Cyril, I am forced to revisit it, to thank them for speaking through Williams to bring me ultimately to Orthodoxy. Indeed, I wrote on Athanasius as I sought to understand myself as an Asian American Anglican, never thinking that I’d become Orthodox, as I had come to him through C.S. Lewis, and thus also through the New Calvinists obsessing over the metaphors of salvation in On the Incarnation. Of course, post-New Calvinism, it was more than Lewis and Athanasius that set me on this Byzantine path; it all started long before in junior high, and after my theological meltdown, I owe as much to Williams, and Athanasius through him, as I do to Zizioulas, de Lubac, Balthasar, and Michael Ramsey. I also encountered Holy Cyril of Alexandria in that class too, as I read about him in Jonathan Hill’s very British and therefore excellent-if-you-like-that stuff (I watch reruns of Yes Minister when I am on break from writing) History of Christian Thought.

But that’s a story for another day, as is how Williams became so rehabilitated for me that I really became Anglican on the way to Orthodoxy-in-communion-with-Rome en route from the realignment. Someday, when I have the courage, I will tell that story. I do not yet, especially because it means that I’ll have to deal with the baggage I have with Anglicanism, the residual elements of it in my practice, and the monetary problem of having to become a paying member of the Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius. Someone told me during my catechumenate that their prayer book would have been perfect for me; the truth is that I am glad that it’s out of print because I’d have had to deal with all my trash then. Others have asked why I never joined the Anglican Ordinariate in the Latin Church, and while Bishop Steven Lopes is a Moreau alum (go Mariners), there was no way I could have done it psychologically at the time (in fact, you can gauge my psychic state when it came to Anglicanism at that point from this piece). On this day, then, I simply ask the Holy Hierarchs Athanasius and Cyril to pray to G-d for me, knowing that it is probably by their prayers in the first place that I came into this Kyivan Church of ours and am creatively involved in its participatory life. Perhaps from here, I will someday be strong enough to do some real ecumenism with those in my Anglican past.