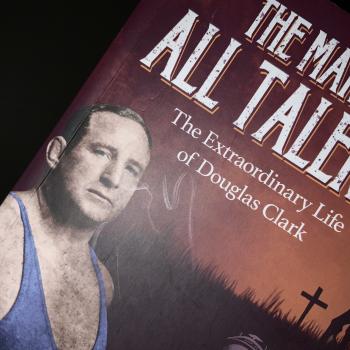

If you have a taste for Victorian novels, and you should, then Pachinko shows that the form is still alive. Forget curmudgeons: not only do “they” still write them like they used to do, but modern authors could teach some of the lesser Victorian lights a thing or two. If he could, even Dickens would learn something from Min Jin Lee’s multi-generational story of a family of Koreans and their complex twentieth century relationship with Japan. This is not Tolstoy, nobody is, but this book is a good bit more readable and easier to follow. Min Jin Lee can plot, create characters, and does dialog splendidly. This is a rare combination. Sometimes a book that covers decades can sprawl (think Michener) and gather strength from being big. Write enough words well about interesting times and the sheer size of the book will get you to the beach. Pachinko is better, because it is not long,

If you have a taste for Victorian novels, and you should, then Pachinko shows that the form is still alive. Forget curmudgeons: not only do “they” still write them like they used to do, but modern authors could teach some of the lesser Victorian lights a thing or two. If he could, even Dickens would learn something from Min Jin Lee’s multi-generational story of a family of Koreans and their complex twentieth century relationship with Japan. This is not Tolstoy, nobody is, but this book is a good bit more readable and easier to follow. Min Jin Lee can plot, create characters, and does dialog splendidly. This is a rare combination. Sometimes a book that covers decades can sprawl (think Michener) and gather strength from being big. Write enough words well about interesting times and the sheer size of the book will get you to the beach. Pachinko is better, because it is not long,

Pachinko follows family and friends of an uncommon common woman: Sunja. Anyone from the lower classes, as I am, should celebrate her story, because her importance, her story as a soul created in the image of God, is made obvious. Her values, including external stolidity and hard work, carry her far. She is described as plain looking, especially at the end of her life, but in a miracle in modern literature, she is allowed sensuality to the end of her life. Sunja has an inner life that most people ignore and that characters in the novel miss to their loss.

She suffers and her family suffers at the hands of the Japanese Empire. Korea is conquered and then Japan loses her war for empire. Japan suffers the only two atomic attacks in human history and occupation by the United States. Meanwhile, the Koreans trudge along trying to survive.

It is not easy.

Japan is not a nation of immigrants, but a nation that has immigrants. During the years of Empire, Japan received a substantial number of Korean immigrants and in the novel this includes much of Sunja’s family. Relationships between “guests” (the Koreans) who have lived in Japan for generations and the Japanese are complicated. Ethnocentrism keeps Koreans in their place and has delayed their becoming part of mainstream Japanese society into the twenty-first century. Pachinko shows that people deal with the society they have. Second class status did not keep some Koreans in Japan from getting rich and one means of doing so, the game pachinko, gives the book a title.

Because this is a book about Koreans, Christianity is present in all the religion’s complexities. Baek Isak, who marries Sunja, is portrayed as a real Christian: a genuine saint. The other Christian characters are just like people in any church: a blend of characteristics as they strive to follow the hard teachings of Jesus as Koreans. Nobody is simple and an irreligious character like Koh Hansu, Suja’s first love, is not just a cad, though he is a cad.

This is one of the best books of the year, but it just misses being a potential “great book.” That’s high praise, but the beautiful writing justifies the compliment. More controversial is why the book is not quite a canonical novel. One way to achieve such status (great text in a great text program) is to create a genre. This novel does not even try this feat. Instead, the book is a product of stupendous research that is the great weakness of the text. A great historical novel (Tolstoy’s War and Peace) is told by someone from outside the cultures described. She is eager to be respectful, good, but that allows too much moral ambiguity.

By the end of the book, you can see the author trying to be fair to Japan. This might be good in friendship and politics, but weakens the novel. The Japanese treat the Koreans horribly and the moral equivalency introduced toward the end rings false, as if the author wanted to honor her Japanese friends. That is laudable in a guest, but too complex for a book already short for the theme. The virtue of the book is that it covers much ground in little space (this is a quick read), but the vice is the “on the one hand” and “on the other hand” voice that intrudes towards the end.

This is a book so good that nobody will call it a Christian novel, a class of books that seems defined as: bad books written by Christians with Christian themes. By this definition, Pachinko is not a Christian novel and no author should wish to be. This is a very good book by a Presbyterian with Christians as characters. If that makes you want to read it, good. If it makes you wish not to read it, too bad, because this book is not propaganda at all. This is a work of almost art, near great.

The book has candid descriptions of horrible events. Be warned, but read this beautiful book if you can stomach a cheerful Calvinist portrayal of man’s depravity to mostly women.