There must have been something wonderfully contrarian in the water of the Hitchen’s house as the two brothers, Christopher and Peter, were growing up.

There must have been something wonderfully contrarian in the water of the Hitchen’s house as the two brothers, Christopher and Peter, were growing up.

Christopher was not always right, but he was interesting and boldly opined. Brother Peter is more in my tribe (being a theist), but proves that theism does not prevent intellectual cussedness. Peter Hitchens always is worth reading whether arguing against thoughtless drug legalization or in defense of values now forgotten.

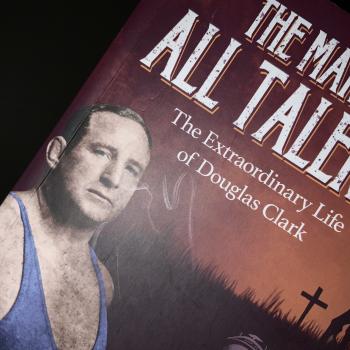

Peter Hitchens’ latest book The Phoney Victory dares commit impiety, though impiety against patriotism, and the legends of the patriotic, does not seem that shocking in the new millennium. Hitchens argues that Great Britain did not fight a good war in War World II, started the war for a bad reason, and ended up a fundamental loser.

Is it possible to read a book such as this and not be misunderstood?

Hitchens has no sympathy for Nazi Germany, thinking that eventually war would have been necessary. He admires the courage of the warriors.

Why write the book?

Peter Hitchens believes that in Britain, myths about World War II infest policy making and cause bad decisions. World War II is the “good war,” appeasement is bad, and Churchillian rhetoric beyond reproach. Britain stood “shoulder-to-shoulder” with the United States of America in a “special relationship.”

Instead, Hitchens pictures World War II Britain as a fading power going to war to prove she still mattered. A debtor nation (to this day!) to the United States from World War I, she was picked clean by Uncle Scrooge before being “helped.” Great Britain came out of World War II a ward of the United States of America. She lost the first phase of the War and was second tier in the rest of it. If Britain had a chance of remaining a great power, losing World War II finished off her chances.

What of the argument?

Hitchens is very good at squashing foolish over simplifications regarding the War. Most of the facts or examples he uses to support his case are well known to anyone who reads more than superficially about the War. “Plucky Poland” was not a good ally, being at once impossible for Britain to save and with a government not worth saving. If you get most of your history from Hollywood (The King’s Speech comes in for a roasting), then you should read the book.

And yet . . .

History is complicated and people say a great many things while making it. People said what Hitchens says they said, but they also said many other things. This is a book pleading a case, but like any contrarian argument when one puts the book down one wonders.

Great Britain and her Empire, most vitally India, faced change soon. Instead of hastening Britains decline to second-tier status, I think winning World War II (and she was on the winning side) arguably created sympathy for plucky Britain. The United States was bound to eclipse the Empire. World War II made her protectors sympthetic to her existence. Colonialism (thank God) fell away rapidly, but in a world where Britain had her basic existence and a measure of dignity guaranteed by one of the two super powers.

Things did not have to turn out even this well for Britain. The United States might have let the Empire fall in much more Roman manner.

Hitchens is right: twisting the lion’s tail was good US politics right up to World War II. At the very least, the great wordsmith Winston Churchill created a United Kingdom that Americans found hard to hate. Good Queen Elizabeth, the last head of state to have served in World War II, has done her bit as well. World War II may have attempted the impossible, keep Britain a great power, but her “foolish” assault on Nazi Germany turned out just right.

And after all, while the motives may have been mixed and timing imperfect, going to war with Nazi Germany and lasting to the finish (unlike the hapless French) was not a bad way to go. The destruction of Fascism was not phoney and if Britain had less to do with it than she claims, then at least she picked the right side and went on picking correctly when she stood stalwertly against Communism in the Cold War.

The American government surely has acted in her self-interest, but Americans (as a people) also love Great Britain. That matters. When Argentina attacked the Falklands, for good or bad, the impulse of many Americans was to stand with our brave ally. Governments had to account for this fact.

Was Hitler ever going to invade Great Britain? Perhaps not. Did the RAF save England? Maybe less that we might want to believe. Historians, and I am not one, will debate this contrarian take.

Why am I not persuaded? This fine book (and you should buy and read it for the good debunking it does) reminds me of an early draft of my dissertation. I made a case for a particular reading of Plato . . .covering all my bases. The entire thing failed when my advisor asked in so many words: “Maybe. You have answered the objections, but why believe this to start?”

The argument was clever, but calling World War II a phoney victory smells wrong. Why?

Perhaps Hitchens is right in all he says, yet still the Nazis are gone and Queen Elizabeth reigns. This may not be victory, but if so, it is one of the better defeats in human history. American governments may say and do cynical things, but the American people were changed by World War II, even if some of what changed us was a Hollywood and Churhillian myth. Britain matters to us more than her size would demand.

As the greatest power on the planet, surely that is some kind of real victory.

God bless the special relationship and the United Kingdom.