Some books are a revelation.

Some books are a revelation.

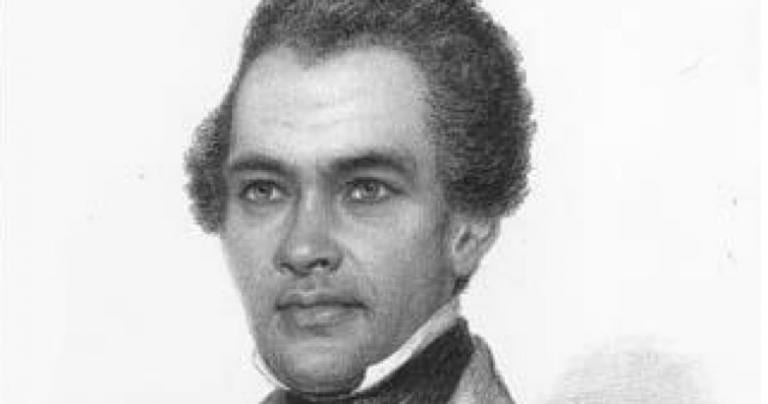

If you have not heard of the best selling novel, published before the Civil War, that more or less accused Thomas Jefferson of fathering a child, Clotel, with an enslaved woman, then you have learned something about who won Reconstruction. The North won the Civil War, but African Americans lost much of the peace when white Northerners reached out too quickly to the white rebels and slavers.

The heroes of abolition and their works, especially those of African-Americans, were pushed out of the memory of the majority. Instead, the focus turned to reconciliation and the “suffering” of the Southern white person after the War. The novelist Thomas Dixon is one example (see The Klansman0 and get the blockbuster early film Birth of a Nation for his horrifically racist whitewash of the pre-Civil War South.) The greater man, the enslaved man who escaped, educated himself, and became a public intellectual was pushed to the margins of “mainstream” culture.

William Wells Brown had told the truth about the slavery culture of the Civil War and the nation that elected scientific racist Woodrow Wilson was going to remember his truth. His novel was too powerful, his place as the first published African-American playwrite, and non-fiction writing to be remembered. Woodrow Wilson showed Birth of a Nation in the White House.

Brown had only the benefits of talent and the truth.

The push into obscurity of a man who helped recruit American troops to save the Union, William Wells Brown, and Thomas Dixon, a man who praised men who tore down our flag, reveals the racist rebellion that won the popular narrative about the War right through Gone with the Wind.

Abolition won the War, but segregation Reconstruction.*

Let’s read Brown and get our history back.

What of his novel?

Clotel is a brisk book, a series of scenes telling the truth about Southern slavery. Like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a twenty-first century reader must learn the language of the time. Early Victorians liked sentiment and would only tolerate so much ugliness. Brown was brutal by the standards of the time. The full truth, the fact of life in a slave culture, was worse, he said in lectures, than words that could be said from a podium.

Read the book knowing that it was shocking and that the sentiment pulled the reader forward into an emotional knowledge of the evils of slavery that Brown could not merely say. Early American Victorians could be brought to act on sentiment that pushed them in moral directions sanctioned by Christianity and republican values. In this sense, the novel is persuasion and Brown (by the standards of the time) was good at it. Brown refused to allow middle class folk, or Americans without slaves themselves, to escape the systematic guilt of slavery. He published the book in Britain while pointing out the British had sown the seeds of slavery in North America. The cultured were not spared:

It does the cause of emancipation but little good to cry out in tones of execration against the traders, the kidnappers, the hireling overseers, and brutal drivers, so long as nothing is said to fasten the guilt on those who move in a higher circle.

Clotel begins with a robust defense of Christian marriage and the unnatural policies that slave culture encouraged:

Marriage is, indeed, the first and most important institution of human existence—the foundation of all civilisation and culture—the root of church and state. It is the most intimate covenant of heart formed among mankind; and for many persons the only relation in which they feel the true sentiments of humanity.

Enslaved husbands and wives were separated and enslaved people had no protection against the designs of their masters:

Reader, when you take into consideration the fact, that amongst the slave population no safeguard is thrown around virtue, and no inducement held out to slave women to be chaste, you will not be surprised when we tell you that immorality and vice pervade the cities of the Southern States in a manner unknown in the cities and towns of the Northern States. Indeed most of the slave women have no higher aspiration than that of becoming the finely-dressed mistress of some white man. And at Negro balls and parties, this class of women usually cut the greatest figure.

The young Clotel is first scene on the auction block put up to bid:

This was a Southern auction, at which the bones, muscles, sinews, blood, and nerves of a young lady of sixteen were sold for five hundred dollars; her moral character for two hundred; her improved intellect for one hundred; her Christianity for three hundred; and her chastity and virtue for four hundred dollars more.

This was honesty without embellishment that had to be written in Europe lest the author be arrested under the Fugitive Slave Laws.

I am not in a place to judge the language or descriptions of the book. They are hard to read (though nothing as ugly as Dixon) and may represent the compromises an African-American author had to make to persuade a white audience. Be warned.

Brown shows that corrupting power of slavery as Clotel is forced into a “marriage” with no legal status, but that she honored before God. She has a child with her “husband.” Americans prided themselves on their love of liberty compared to old Europe, but:

Clotel now urged Horatio to remove to France or England, where both her [sic] and her child would be free, and where colour was not a crime.

Brown makes an interesting argument when he shows that a Christian defense of slavery (put in the mouth of an intellectually fatuous preacher) drives men to infidelity. Since most readers of the novel would not want infidelity, the Christian liberty-loving daughter of the preacher is the attractive option. Against her father’s rambling defense of the Bible and slavery, his friend’s love of liberty yet lack of a moral compass, she argues that what is good for humans in general is the will of God and what degrades them cannot be. She concludes:

This single passage of Scripture should cause us to have respect to the rights of the slave. True Christian love is of an enlarged, disinterested nature. It loves all who love the Lord Jesus Christ in sincerity, without regard to colour or condition.

Brown demonstrates that defenses of slavery are based on particular passages pulled out of historical context that ignore the message of the New Testament. Infidelity in response threatens the moral order. Christianity and liberty must be linked. This is redemptive:

A silence followed this exhortation from the young Christian. But her remarks had done a noble work. The father’s heart was touched; and the sceptic, for the first time, was viewing Christianity in its true light.

The novel has fictional characters enacting real events, more tableau than plot. The ending is moving, slavery corrupts all. Still the soul created in God’s image can never be conquered. As a man Brown could be enslaved, but not made a slave. He can be ignored, but not refuted. His truth goes marching on.

Thomas Jefferson almost surely fathered the children of an enslaved Sally Hemings.

Lord Jesus Christ, son of God, have mercy on us.

———————————————————-

*Not all of it, of course, and leaders like US Grant, imperfect, still did much good in office. Sadly, much more was undone when “Lilly White Republicans” forced powerful African American politicians into a powerless role in the Republican Party.