Barnaby Rudge defies Hollywood and shows the Victorians were better than we are in at least one respect: they would read a longish novel centered on “natural.” They might have used the term “idiot,” but they not only allowed him dignity, but would cheer for him.

This first of Dickens’ historical novels (with the better Tale of Two Cities) centers on the Gordon Riots in the London of 1790 . . . bearing a relationship to Dickens as the First World War does to me: distant memories of great-grandsires.

The riots were a great spasm of traditional English anti-Catholicism and Dickens has no sympathy for any of it. As his Child’s History of England proves, he is conventionally Protestant, but no hater. Killing other Christians in the name of Christ is bizarre to him, as it should be to any Christian, and he gives it the literary thrashing it deserves. He shows that hypocrites, bigots, and small minded men use religion, and the important differences of creeds to enrich themselves.

I think, however, the book is mostly about dealing with history. Some bend with the will of Providence and become happy whilst others try to control history to their own benefit and are broken. Those that mourn history are also mistaken: a good lesson for conservatives such as I am who do not like the direction of our nation at present. The mistake of the “good man” who mourns history is not in his opinions, he is right to bemoan evil, but his lack of faith in Divine Providence.

Dickens shows that Christ’s man can be a jolly man even in the midst of riots and loss.

Here are questions I had about the book as I read it:

Why is the book called Barnaby Rudge? Superficially he is not the “hero.” What is the significance of both characters who have the name to the meaning of the book?

Place is important to the book: London most of all. The Maypole Inn is another example: you cannot read the book without wanting to go, it is Rivendell for the rest of us. How is place formed and renewed in the novel?

Parents, good and bad, are central as are the relationships they have with their children. Some parents will not grow up, some merely grow old, and others grow to be great. What do we learn about good parenting and being a dutiful child from Dickens?

The book assumes the truth of Christianity, but shows the Faith being warped by bad men for their own ends. Why could some believers avoid the pitfall of being so right they become wrong?

The good characters, male and female, find happiness in home. What is the image of home presented in the book? Is it perfectly Biblical? Where do bad assumptions intrude and limit the characters?

Reflect on the death penalty in light of Barnaby Rudge. Is it necessary or good in an affluent culture? Are their alternatives? Is there a Christian view?

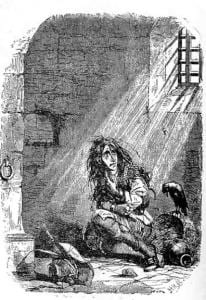

The raven “Grip” is important to the story and is so impressive he inspired Poe to attempt to better Dickens’ use of a raven. Read Poe’s famous poem “The Raven.” How are the creative imaginations different in the two great men?

The book ends with two older men facing each other in a long delayed battle. When done with the novel, you will wonder with me if Dickens’ isn’t making use of the story of Cain. Does blood cry out from the earth when shed unjustly? Does history eventually make right great crimes? What does that say about Europe after the Holocaust? Russia at the end of the Gulags? America after slavery and abortion on demand?

Read Lincoln’s Second Inaugural in the light of Barnaby. What does the President think faces the nation of his day? Is that what happens to the characters of the novel?

At the end of the book, the character of Lord Gordon, mad and exploited, stuck with me. As a Christian, I dread the image of a decent man manipulated to do bad things in a good cause. It is so easy to do, but the command of the Savior to “love my enemies” would surely check abuse, riot, and the temptation to become a persecutor.

It should, but it often does not.

Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me, a sinner.