When we listen to our times, our church, whose poetry are we hearing and whose hymns are we missing?

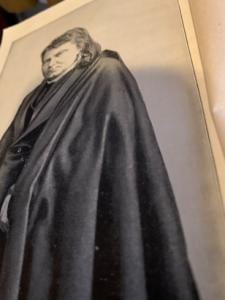

I own a battered green book retrieved from a Galveston library discarded book bin. The 1896 second edition contains the story of a very interesting man who did some good in his time, was loved by many, but who got the one big event of his lifetime more than wrong: Father Ryan, Confederate chaplain, priest, and poet. He was evidently a brave man and did not think (at least in retrospect) that he was fighting for slavery. He was a much read poet in his time. At his death, his publisher (PJ Kennedy and Sons, New York) put out an expanded edition of his poetry, including some posthumous work. The best of this poems, some very good, center on the liturgical year, many are haunted by sorrow, and there is much one could learn about suffering and death. Yet titles like “The Prayer of the South,” “The Conquered Banner,” and “C.S.A.” show how much he missed and the harm he did.

He misunderstood everything in his Reconstruction times, because he did not hear the truth tellers all around him.

Consider one example-

While Father Ryan was writing of the Confederate Army:

Do we weep for the heroes who died for us,

Who living were true and tried for us;

The Martyr band

That hallowed our land

With the blood they shed in a tide for us?

Frances Ellen Harper Watkins wrote of those same days:

LEARNING TO READ

Very soon the Yankee teachers

Came down and set up school;

But, oh! how the Rebs did hate it,

—It was agin’ their rule.

Our masters always tried to hide

Book learning from our eyes;

Knowledge did’nt agree with slavery —

’Twould make us all too wise.

Watkins, abolitionist, fought for the rights of her brothers and sisters in the nation before and after the Civil War. Her just hopes were denied in part by the sort of sentiment that Father Ryan encouraged in white Southerners who not only did not repent of the sin of slavery, rebellion, and injustice, but gloried in the Lost Cause. These white Americans were encouraged by Northern Copperheads. After all, Ryan’s publisher was in New York.

If Father Ryan himself was a kind man, the generations that grew up on his writings or those like him raised generations who practiced Lynch law and acts of terrorism.

Father Ryan does not hear her voice, ignores Christians such as Priscilla Jane Thompson who complained that the “muse of poetry” has often heard “Caucasia’s daughters,” but the time was long past to listen to “equally deserving — The oft slighted, Afric maids.”

Father Ryan venerated the Confederate Battle flag during Reconstruction: “Furl that banner! True, ’tis gory, Yet ’tis wreathed around with glory, And ’twill live in song and story.” Meanwhile, Sutton Griggs urged white Americans to not “hinder the hand” of the freedman. Griggs was ignored while Ryan wuthered on about Robert E. Lee. Father Ryan ignored the poetry of gentle Anne Spenser, the very high Victorian voice of Mary Weston Fordham, and the Southern sound of George Marion McClellan. All these black American voices shared many of Father Ryan’s values, even his style of writing, just rejected his false glorification of days best described as hell.

There is an alternative to history where men like Father Ryan listened to their betters, saw the common culture, and made restitution. Instead of living in mourning, the Southland could have had a year of Jubilee.

We cannot go back. We can amplify some of the best contemporary voices and listen, always listen, to hear what we might be missing. God help us avoid the reactionary error of an otherwise decent man, Father Ryan.