David Russell Mosley

10 February 2014

On the Edge of Elfland

Beeston, Nottinghamshire

Dear Friends and Family,

Here’s a relatively brief book review I’ve written for John Milbank’s The Legend of Death: Two Poetic Sequences. Eugene: Cascade Books, 2008.

Readers familiar with John Milbank’s work, particularly essays he has written but also books like The Word Made Strange and Beyond Secular Order (which I’ll be reviewing in the next few days), will not be surprised that John desires poetry and desires that it be written to express metaphysical and theological truths. What readers may be unaware of, however, is that John is a poet himself.

The Legend of Death is John’s second published book of poetry, that I know of, his first being The Mercurial Wood (which I haven’t read, yet). This book is written, like much of John’s work nowadays, in two sequences. The first sequence, On the Diagonal: Metaphysical Landscapes, is a series of what appear to be primarily occasional poems about the Nottinghamshire and Virginia landscapes. These poems, however, are not mere descriptions (though I’m sure they would be lovely if they were) but also reflections on the metaphysical. John writes poems with titles such as ‘Hymn to Iamblichus on May Morning’, ‘Cosmos’, and ‘On the Lizard’. This collection is both and fun and profound, often within the same poem.

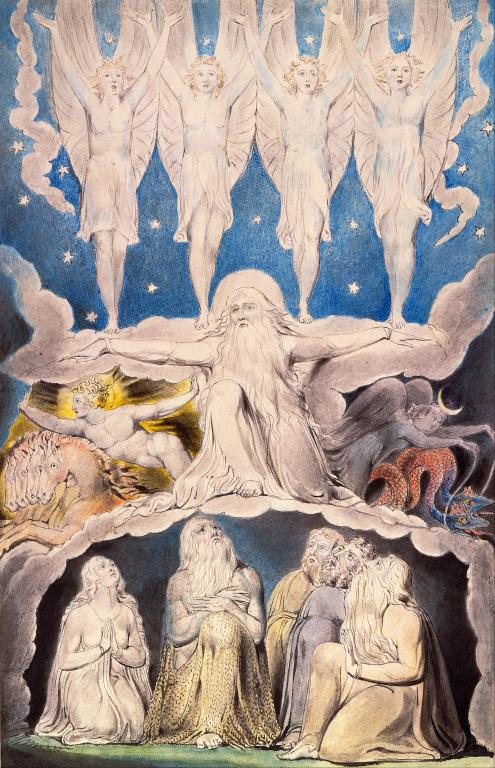

In the second sequence, The Legend of Death, which gives the book its title, Milbank fuses together bits of mythology, theology, and geography taking his readers on trip beginning in the other Britain, Brittany, and working his way into Britain itself in a relatively northward moving pattern. Thus the poems here collected shift from the Celtic and Arthurian to the Nordic/Anglo-Saxon world of Woden. In these poems John gives us what I can almost describe as death as life. A single reading is not enough to plum the depths.

Accompanying each sequence are two essays wherein Milbank lays out the theoretical and theory of poetics behind the poems in each sequence.

In the end, Milbank has proven himself to this reader not simply a poetical person, but a poet. True, Milbank is not, perhaps a perfect poet, but I am not a good critic to tell you why. For my own tastes, I tend to prefer poetry with more structure, more intentional rhythm, meter, and rhyme, but can attest that this is terribly difficult poetry to write well. What Milbank does very well in these poems, however, is to dare theologians and philosophers to poetise, that is to write poetry. Oh this may not have been even remotely a goal of his (though I intend to ask him), but nevertheless, Milbank here reminds us implicitly that Christianity (and Judaism) is the the religion of the Psalms, the religion of Poets (like Gregory of Nazianzus, Ephrem the Syrian, Dante, the Pearl Poet, Milton, Donne and so many others). Milbank reminds us that the best theology and best theologians ought often, though not always, also be poets. Even should you hate the poetry contained within these pages, if you call yourself a theologian or a philosopher, let this book remind you that we are a poetical people, that we are poems ourselves, created by the Poet of the Cosmos (though not in the Whiteheadian sense).

Sincerely yours,

David Russell Mosley