David Russell Mosley

Advent

10 December 2014

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Friends and Family,

Last year I wrote a post responding to a new professor at my alma mater on Father Christmas. The problem, according to Dr Samples, is that Father Christmas/Santa Claus has become a source for perpetuating economic disparities. As I noted in the post, a friend of mine once told me that she discovered Santa wasn’t real because the rich(er) kids down the road got more and more expensive presents than she did. Recently, a new friend of mine, writing an excellent series of posts concerning the United States’s unnamed god, Affluence. He suggests that by training our children to write Christmas lists is to train them in the worship of affluence by teaching them to covet, to desire things they don’t have but want to have. However, I think the Christmas list and the presents brought by Father Christmas do not have to be trainers in covetousness nor perpetuations of economic disparity.

Now, first let me say that nothing will stop some parents from lavishing their children with presents at Christmas time. I was spoiled as a child, all the time, not simply at Christmas. However, I was trained not to brag about my presents because not everyone could get the same things I did. This actually taught me to share, but this is besides the point. If we cannot permanently change how our given neighbourhood parents “do” Christmas, as regards presents, we can change how we and our churches do it. Let me suggest at least one way.

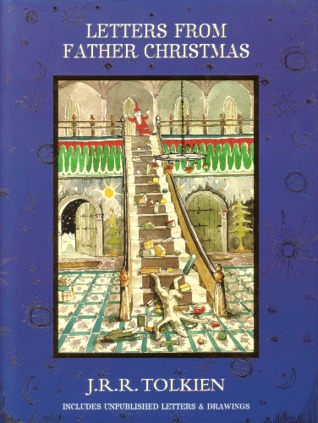

A professor of mine talks about training his children’s desires. He will ask them what they want (desire) for dinner. They might say chips (fries), or candy, or fast food. He will then tell them that instead of any of those things they are having baked fish (or whatever has been made for dinner). The point is to teach them what they ought to desire. By allowing them to voice what they really do desire, but not give it to them, he is helping them learn what they ought to desire versus what they do desire in a given instance. I’m sure this ends in meltdowns and tears often. I’m equally sure that some nights he gives in. But the point is to try, to try to change their desires from low things, that can be good at times, to higher things that are much better. When we allow our children to make Christmas lists that they send to Father Christmas, we’re allowing them to voice their desires. Yet we are not bound to get anything on those lists. Some items may be intangibles, I frequently asked for snow. Others may be well outside of the parents’ price range. J. R. R. Tolkien used to write letters from Father Christmas to his children. While as the stories grew so did the Father Christmas mythology, equally, most of the letters are a way of explaining why the children didn’t get everything on their lists; typically, this is because of some catastrophe that happened at the North Pole. I think we can take this a step further.

I do not have children old enough to ask for anything for Christmas yet, so these are purely ideals that will likely change over time. Nevertheless, I think there is a way that we can allow our children to give voice to their desires in the Christmas list that will be beneficial to them, especially when they don’t receive all the things they asked for. A child might ask for the latest video game system and instead might get a book. A child might ask for a pony, or even a puppy, and yet only get an art set. It’s likely they will be sad not to get all the things on their lists. Yet, if we as parents continue to get them things that are good for them (I am not suggesting that video games, ponies, or puppies are inherently bad for children, just that they represent rather expensive options that parents may not be able to buy their children) we can train them in their desires; and I think we will see a change in what they ask for, because their desires will be being properly ordered.

Parents of children who actually ask for presents, what do you think? Am I completely off base here?

Sincerely yours,

David