Ordinary Time

12 June 2019

On the Edge of Elfland

Manchester, NH

Dearest Readers,

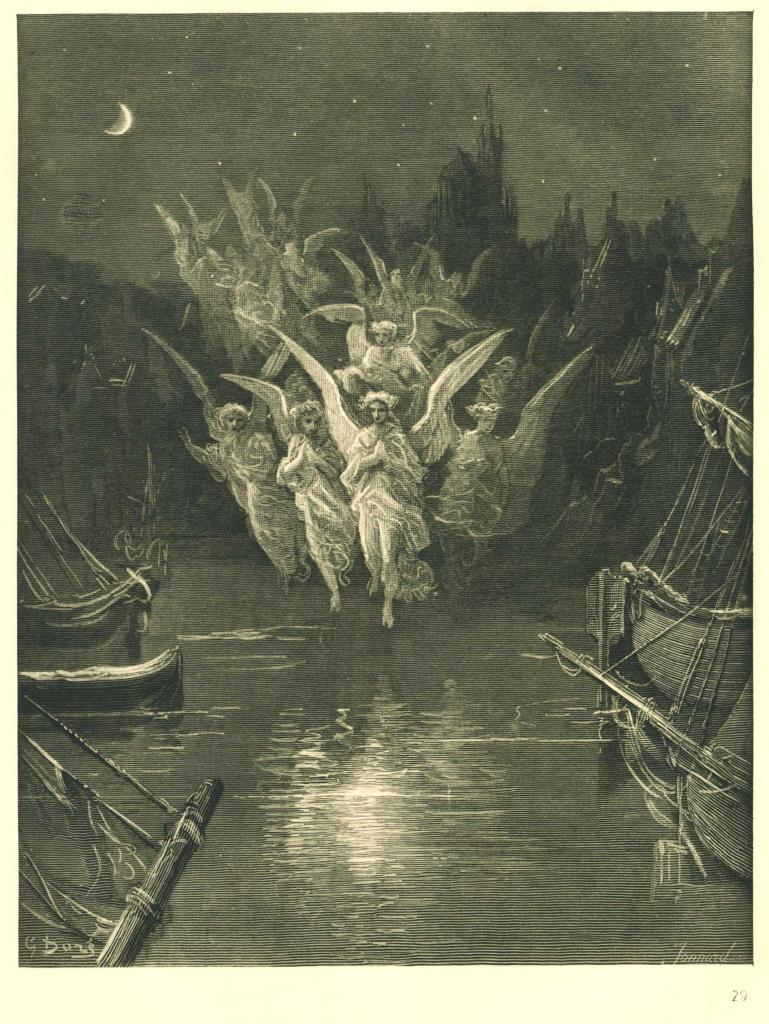

“It is an ancient Mariner,

And he stoppeth one of three.”

So Coleridge begins his most famous, and perhaps his most important work. And like the one of three, I have been so stopped. Coleridge has been much on my mind of late, this poem not the least. Like the wedding guest who is stayed by the Mariner’s angelic version of the evil eye––the good eye, perhaps––I cannot help but wonder why I was so stopped. Why has Providence decided that this was to be the year of the Mariner for me? I don’t know. It has been months since I last read the poem. In that time I have read Malcolm’s excellent biography of Coleridge and have nearly finished Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria. I had read the poem before, but it did not stop me then. It has done so now.

Something in me has changed. I have, like the wedding guest awakened a sadder, and, I hope, a wiser man. I am haunted by it, by Coleridge himself. Here I was, sitting outside, reading and smoking, when I felt that familiar call. That call to put words down, to say something. And as I felt this call of the muse, it was the Mariner who first entered my thoughts. Who is the Mariner? Wherefore stopp’st he me? Guite as you know claims that Coleridge is the Mariner. Even his tombstone reads, “Stop, Christian passer-by! – Stop, child of God ….” And so I am stopped, gripped by his story, by his life. But what does this prophet of England want to say?

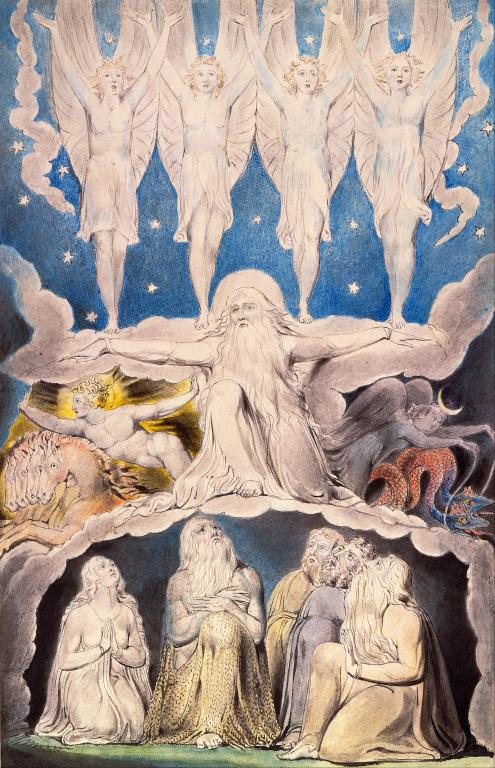

I am not, at least not yet, a Coleridgean scholar. But I cannot help but think Coleridge has twinned reasons for stopping us. The first is found most easily in the Rime, but can be seen in many of his works. He stops us so we can see, so we can see the world around us. He stops with his gothic ballad, with his meditations on the ministry of frost, so we will see the world, so we can remove the film of familiarity and see with fresh eyes that the cosmos is charged with meaning, meaning we do not place on it, but discover there. Meaning does not reside simply within us to place on objects as they fit some utilitarian scheme. Rather the tree, the rock, the star, the angel, the genius of a place have meaning knit into them. Yet while things have meaning in themselves, we are not cut off from them.

And this is the second reason Coleridge stops us. He stops us to show us that while meaning resides within the things themselves, we play a naming and a shaping role. In his Biographia Literaria, Coleridge gives what is ultimately a new definition of imagination. The medievals defined imagination as the ability to hold images in one’s mind. Today we mean by it the ability to create non-existent things, to write poetry or stories, to paint, to make music. But Coleridge says there are two kinds of imagination, the primary as the secondary:

“The primary imagination I hold to be the living power and prime agent of all human perception, and as a repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I AM. The secondary I consider as an echo of the former, coexisting with the conscious will, yet still as identical with the primary in the kind of its agency, and differing only in degree, and in the mode of its operation. It dissolves, diffuses, dissipates, in order to re-create; or where this process is impossible, yet still at all events it struggles to idealize and to unify.”

There is much to unfold here, and I wish to be brief. It seems that Coleridge connects our imagination to the creating and meaning infusing or shaping power of God. It participates in God’s creativity by naming and shaping the things around us. As Tolkien wrote to Lewis in his poem, “Mythopeia,”

“Yet trees and not `trees’, until so named and seen –

and never were so named, till those had been

who speech’s involuted breath unfurled,

faint echo and dim picture of the world,

but neither record nor a photograph,

being divination, judgement, and a laugh,

response of those that felt astir within

by deep monition movements that were kin

to life and death of trees, of beasts, of stars:

free captives undermining shadowy bars,

digging the foreknown from experience

and panning the vein of spirit out of sense.

Great powers they slowly brought out of themselves,

and looking backward they beheld the Elves

that wrought on cunning forges in the mind,

and light and dark on secret looms entwined.”

On the one hand, our minds behold the meaning of the world around us. On the other we help shape and make that meaning. It is no accident that God gave to humanity the task of naming things, for to name something is to declare something real about its nature and to help shape what it is. This may well explain why matter seems so dead to us now, why it so often seems as those the fairies all have fled, because we have renamed the world with the lens of utility of matter without meaning except as it can be commodified by me.

To you I may seem a fool talking of the meaning of trees, the shaping power of names, of fairies. But this is the film Coleridge has helped me remove, and not he alone. This is what poetry so often does, or should do. It should remove the film of familiarity, it should help us restore a vision of creation as something created by a Creator. And what a terrible and wonderful gift this Creator has given us by tasking us with tending, naming, and shaping the very gift that is our reality. The Wisdom of Christ is foolishness to the world. But to the cosmos? Wisdom is the glory of the Lord.

So tolle lege, take and read, and perhaps you too will wake a little sadder and a little wiser tomorrow morn.

Sincerely,

David Russell Mosley