13th Sunday in Ordinary Time 2019

The Edge of Elfland

Concord, New Hampshire

Dearest Readers,

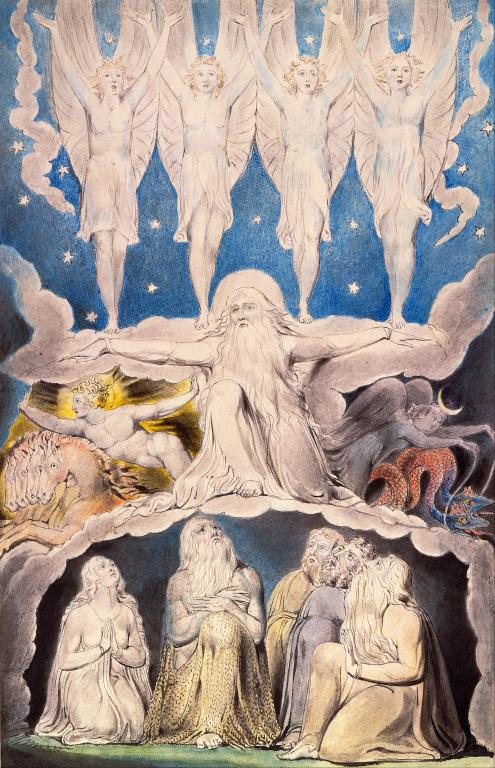

There is a word often bandied about, especially in the Christian landscape these days that I’m not certain has been adequately defined. That word? Imagination. You might have seen it used with the modifier Catholic, or perhaps sacramental, or dialectic, or analytic. In nearly every case, the actual meaning of the word imagination goes largely undefined. Now, in a small space like this, I cannot go into full detail on the meaning of the word imagination. And I have already begun to address it in a recent letter on Coleridge. Nevertheless, I want to dig a little deeper into the meaning of this word.

First, a reminder. The original meaning of the word, imagination, seems to be the ability to hold images in one’s mind. It usually fell in the hierarchy of knowing just after the senses and before reason. By the sense we take in pictures of the world around us. By the imagination, we retain those pictures even when the object perceived is gone. By reason we combine those images into meaning, perhaps even new ones. For example: I see my wife standing before by way of my senses. When she leaves, I do not forget what she looks like or that she exists because my imagination and memory allow me to hold pictures of her in my mind, capable of recall whenever I desire, and sometimes when I don’t intend to, as loved ones are wont to do. But reason allows me to do something with these images which my senses and imagination cannot. Reason allows me to consider how my wife might address a certain issue. It also allows me to imagine what she might look like with blonde hair since I have seen both blonde hair and my wife before. And even though I have never seen her with blonde hair I can recombine the images held in my mind in new ways to create new images. But more importantly, my reason, according to this view, allows to see that my wife is my wife and not just some woman who appears before my eyes from time to time. She and I share a relationship, one that is made known to me through my reason interpreting the data of my senses as retained by my imagination. So much for the old view.

Coleridge, and following him, C.S. Lewis see imagination in a different way. They have not arrived at imagination as we commonly define it today, creative ability or talent. Rather, they see imagination as a means of participation in God the Creator. For Coleridge, as I noted before, imagination is, in essence, a means of perception which allows us both to understand and to shape the world around us. Lewis seems to arrive at a similar conclusion in his essay “Bluspels and Flalansferes.”

The main point of this oddly titled essay (the title makes abundant sense if you read the essay) is that we cannot talk without attending to the metaphorical nature of language. Lewis is taking on the notion of scientists believing they use a pure language, devoid of metaphor, that even when a word once had a more metaphorical meaning (as attention used to have the sense of something being stretched) its metaphorical use is no longer in play and so something pure is meant by the word attention. Lewis argues, rightly, that this is nonsense. While, as a professor of biblical Greek I know often said, a word’s etymology is not its meaning, it is also not uninvolved in the word’s meaning. Ekklesia which we often translate as church, may not have meant to the New Testament writers the called out ones (ek-klesia) and may have meant to them something more like the gathered, but we cannot say that the notion of being called out from a larger group was completely absent from the first and second century usage. In fact, without directly citing Barfield, Lewis uses one of Barfield examples of how for ancient man a word often meant all of its meanings at once, so that when we talked about breathing, we automatically meant the act of filling one’s lungs with air, spirit, and wind. Were we to try to remove from the word wind any sense of breath or spirit, the word wind would ultimately lose its meaning.

At the end of the essay, Lewis turns from words to the imagination. He writes:

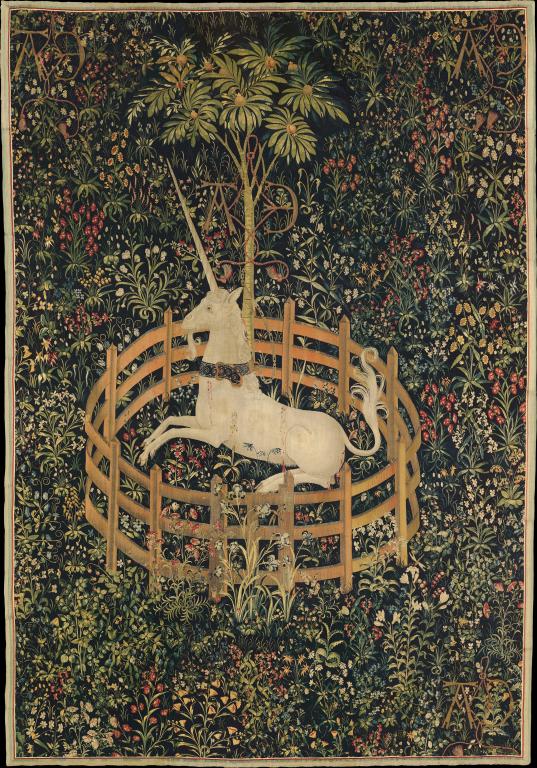

But it must not be supposed that I am in any sense putting forward the imagination as the organ of truth. We are not talking of truth, but of meaning: meaning which is the antecedent condition both of truth and falsehood, whose antithesis is not error but nonsense. I am a rationalist. For me, reason is the natural organ of truth; but imagination is the organ of meaning. Imagination, producing new metaphors or revivifying old, is not the cause of truth, but its condition. It is, I confess, undeniable that such a view directly implies a kind of truth or rightness in the imagination itself.

What Lewis says here is that reason’s job is to be concerned with the truth of something. It dictates whether or not my wife is in fact my wife, by virtue of our having been married and not having dissolved that marriage. But imagination is the organ by which I understand what it means to be married, to be someone’s husband, to be had, to have a wife. Imagination is the means by which I understand what the truth means, without it, reason becomes simply a set of facts with no meaning, and is thus nonsense.

In a future letter, I hope to address the modifiers, particularly Catholic and Sacramental that have become popular in modern discussions about religion and imagination. But for now, I want to leave you with this important note: if Lewis and Coleridge are right about the imagination, then to some extent, it requires no modifier. Imagination, like reason, is a profoundly human reality, is created good, and can, like reason itself, be misused and abused. But none of this means that the imagination is not an essential aspect of human knowing, and we ignore it at our peril.

Sincerely,

David Russell Mosley