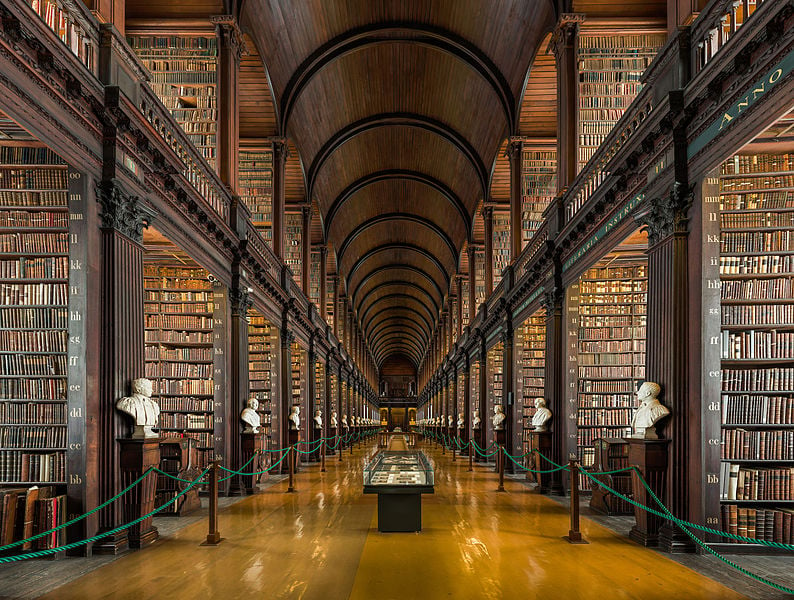

The Long Room of the Old Library at Trinity College Dublin.

Date 21 July 2015

Source Own work

Author Diliff

(CC BY-SA 4.0)

Ordinary Time

5 November 2018

The Edge of Elfland

Manchester, NH

Dearest Readers,

As many of you know, I work for a small, private, Catholic high school in the classical tradition. In case you don’t know what that means, let me, briefly, break it down for you. We are small, around 100 students (but also growing). We are private, meaning we are not a diocesan school. We are Catholic, meaning that while we are not a diocesan school we are still allowed to officially call ourselves a Catholic school. And we teach in the classical tradition, meaning we teach Latin to 5 out of 6 grades (we run 7-12) and that we use Socratic Discussion as our primary way of teaching our classes. It is this last I want to focus on for teaching by discussion means we need to have good things to discuss, which is why most of our classes read primary sources.

C.S. Lewis in his introduction to an older translation of Athanasius’ On the Incarnation tells us of the importance of reading primary sources before secondary. It is better, he argues, to read Plato’s Symposium first, then read someone’s opinion on it. After all, what you’re really learning when you read someone else on the Symposium is their view of the Symposium, but they may very well be wrong and you have put yourself in the position of not being able to judge whether or not they are. Fellow Patheos Catholic blogger, Scot Eric Alt, has made a similar argument when it comes to Church teaching on social issues. However good, or bad, someone’s book on Church teaching may be, the only way to even attempt an unfiltered view (an impossibility as you will immediately begin filtering it yourself) of Church teaching on any subject is to read Church documents on that topic.

In my own classes––I teach both literature and theology––I do everything I can to ensure that we’re reading primary sources. In English classes this is rather easy. We read The Divine Comedy and then discuss it. We read Pride and Prejudice and then discuss it. In my theology classes, or at least in my Apologetics class, it has proved a little more difficult. These classes are equal parts catechesis for young people that might be offered at a parish church and academic teaching as ought to be found in a high school. So, in Apologetics we read a kind of blend. We read Holly Ordway’s Apologetics and the Christian Imagination, C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity, and Kreeft and Taccelli’s Handbook of Christian Apologetics, but we also sample from the Church Fathers and medieval theologians, especially Aquinas. What I love about my school, however, is that whatever we read the students have and are learning the skills necessary to pick up an unfamiliar book, read it, and come to informed conclusions about it.

As various literary and now theological theories have arisen (many of which being helpful in their own right), I still find it important to return to the sources. We need to read these books and these people for ourselves and not simply rely on those who have read them before us. This is not to say that we should eschew tradition, I did stop being a Protestant after all. I am not arguing that we should all read the Bible in a vacuum or that we should read Aquinas in vacuum. But we must recognize the difference between reading the Bible and reading Aquinas. The Church has magisterial, official things to say about Scripture and how to interpret it. The Church does not have a magisterial way of reading Aquinas or Jane Austen. No, we must come to these books open to what they actually say, attentive to the words and attitudes present in them. Yes, just as with Scripture, we need to understand cultural and historical differences; we have to understand that we cannot read The Consolation of Philosophy with the same eyes as those reading it in the fifth century. But we can still read it first, attentive to what it actually says, so that perhaps we can be transformed by it.

As a final note I want to address the kinds of books we read. Right now, I have noticed trends of eschewing some of the older books, the kinds of books I typically teach, in favor of newer books by marginalized authors. These books are more approachable and more likely to make life-long readers. Or so we are told. Now, I only have anecdotal evidence at present and I am not interested in getting into a fight. I do think it important that students hear from previously (and often currently) marginalized and oppressed voices. But I also think we inappropriately undervalue the older books which laid a foundation for the newer ones. What is more, I think we underestimate out students. This year, for the first time ever at my school, I taught Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy to a group of high school sophomores. Now, I won’t claim that they understand every intricacy of that book or that they could write a college level essay on it. Nevertheless, they read it and understood what it was saying. One of them even declared it the best old book they have ever read the school (and now we’re reading The Divine Comedy which I expect to supplant Boethius). In other words, I agree that we need to ensure marginalized voices are being heard, but I don’t think that means we have to stop reading the Great Books. In a different class, in order to show the importance of poetry, I played the video of Stephen Colbert breaking down a song by Childish Gambino and Chance the Rapper because Colbert connected it back to Gilbert and Sullivan and then to J.R.R. Tolkien. The old and the new make good bedfellows, we just have to be willing to listen to both, which means for many of us, returning to the sources.

Sincerely,

David