Lent

21 March 2019

The Edge of Elfland

Manchester, NH

Dearest Readers,

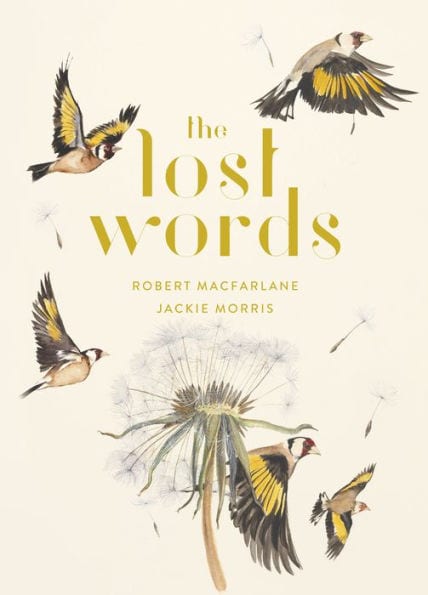

Recently, thanks to the work and suggestion of Malcolm Guite, I have had the opportunity to read The Lost Words. The book is written by Robert Macfarlane and illustrated by Jackie Morris. The origin of the book can be found in the most recent edition of the Oxford Junior Dictionary. For reasons best known to themselves, the editors decided to remove somewhere around 40 formerly common words. What did these words have in common? They were all about nature. In their place words such as broadband, blog, attachment, and cut-and-paste.

Author Robert Macfarlane and illustrator Jackie Morris were not going to take this lying down. So, they decided to write a spell book, a book incantations calling upon 20 of those words to work their magic. The 20 words Macfarlane and Morris have incantated are as follows: acorn, adder, bluebell, bramble, conker, dandelion, fern, heather, heron, ivy, kingfisher, lark, magpie, newt, otter, raven, starling, weasel, willow, and wren.

Macfarlane turns each word into an acrostic poem evoking images and stories about the creature represented. The most moving of which for me was the spell for the willow. The willow, a tree which has always enchanted me, is set up as a whisperer with some secret to tell that we long to hear but cannot, “you will never know a word of willow––for we are willow/and you are not.” When I read that final line for the first time, it chilled me. My skin tingled. And then I turned the page and saw the beautiful, two-page illustration Jackie Morris provides. A large, leafless, twisted willow leans out over the water as the moon rises behind, just beneath the willow’s twisted arch far in the distance and set above the far off trees.

The book is, in a sense, an illuminated incantus. Each spell is not only accompanied with a facing-page illustration, but before it comes a jumble of letters, the letters of the coming word bolded or colored differently. Then after comes a two page spread setting the spell and the word in their proper supernaturally natural context. These pictures help bring to life the words and thus help enact the spells. It is, in a way, like the illuminated manuscript Lucy read’s in Coriakin’s house. The magician’s book has pictures that move as the spells are read. And I swear I saw a twitch in the otter’s tail and heard the wordless whispers of the willow.

This book should delight children and adults alike. The poetry is complex following different patterns. Sometimes it is rhymed, other poems are alliterative. Sometimes the acrostic is only one line per letter, sometimes the letter only serves as the beginning letter of a much longer stanza. It gives a sense of wood-longing, of desire to be out in nature so as to see the spells most fully enacted. And, what is more, it gives a sense that these words are important, not because they are good to know, but because they convey something of the reality of the objects they signify. There is no nominalism here. Rather the very word “raven” provides the ground upon which the poem can be told. The acrostic nature of the poetry shows the deep-seated and mutually informing relationship between a word and its object. Macfarlane and Morris invite the reader inside the words and thus into the creatures themselves, into ravenness, willowness, acornness. And when once read, the spell has been enacted and the reader is enchanted.

Sincerely,

David Russell Mosley