Lent

7 April 2019

On the Edge of Elfland

Manchester, NH

Dearest Readers,

Recently I came across a BBC about the use of folklore in conservation efforts. A team from the University of Birmingham conducted an experiment to discover what made young students more likely to be in favor of conservation efforts. They chose magpie because they are not “poster animals” for conservation efforts like eagles or pandas. One group was given scientific information about magpie. Another folkloric information. A third was given both and fourth none. The results showed that children who received the folkloric information were those most keen for conservation.

This is something I have noticed myself. In both Ireland and Iceland local belief in elves and fairies has halted potentially dangerous to the environment construction. Why? Why is it that when scientific explanations fail to inspire conservationist efforts, at least in children, do folkloric and mythic explanations? I believe the answer lies in our human nature.

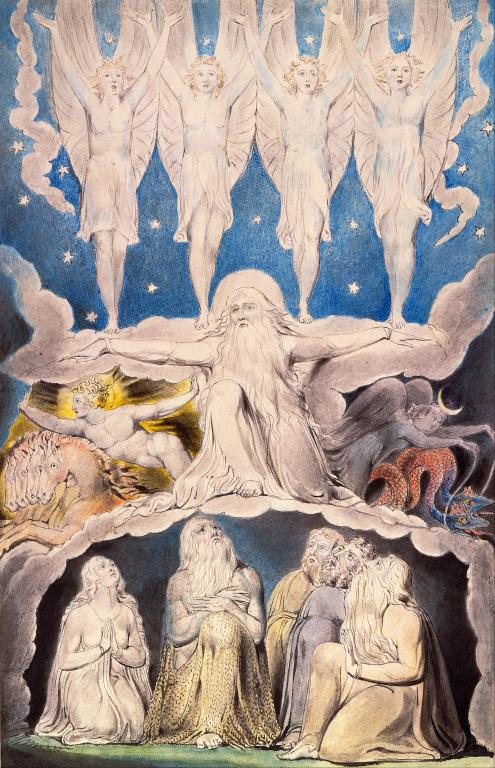

Human beings are inherently poetical, and much of our earliest poetry and song are concerned with telling mythic, comsgonic, and folkloric/Faërie stories. One needs only look at the beginning of Genesis or the Enuma Elish or the Proetic Edda to see that this is the case. Story, therefore, and also poetry, allows us a deeper connection with the world around us. It reminds us that the world is not just what our senses can perceive, but that there is something deeper going on, that there is a real relationship between us and the world around us.

Coleridge understood this when he wrote at the end of the Rime of the Ancient Mariner:

“He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.”

For Coleridge there is not a nature-humanity dichotomy. We belong to nature and it to us. We know this not only through our experience of the phenomena of the world around us but also through the stories we tell. And this too is something I love about the book The Lost Words, which I reviewed here. Rather than simply providing definitions or etymologies of the words being excised from the students’ dictionary, Macfarlane wrote poems. He wanted us not to engage with these words from a purely scientific level, but to encounter them as realities. Folklore, myth, fairy-stories help us engage with the world around us more deeply.

Part of this, I think, is because it removes us from the laboratory. Science is often, though by no means always, concerned with removing all the variables and looking a pure object, experimenting with it. Folklore is precisely interested in maintaining the variables. It adds variables. What if ravens, for example, don’t just eat carrion? What if they are also the messengers of Odin? What if it really is bad luck not to greet the first magpie you see on a given day? When I lived in England, I would always do my best to greet the first magpie I saw with a gentlemanly, “Good morning, Mr. Magpie.” I did this not because I feared bad luck, but because I liked how it made me pay attention to the world around me. I was always on the look out. And this helped me to pay attention to the magpie in front of me as well as to come to understanding of magpies in their habitats. I didn’t want the lab’s magpie, or the physicist’s spherical chickens, I wanted the magpie in the park during my afternoon walk.

This attention to story is essential to children’s education, but it is not for children only. We adults too can learn to better engage with the world around us, and thus care for it better, precisely if we pay a bit more attention to myth and Faërie. Perhaps reminding ourselves that four-leaf clovers are lucky will stop us from inundating our yards with deadly poison to keep them at bay. Perhaps the ritual of saying, “Good morning, Mr. Magpie,” will make us more attentive to the destruction of their habitats. Perhaps even a belief in elves and fairies will keep us from building roadways or fracking on lands important to the fair folk. Perhaps a little more superstition can lead us to a healthier engagement with the land. Perhaps better engagement with the land will allow us to turn our eyes to the stars with wonder and not utility. Maybe even then we can find ourselves contemplating the world around us and see the vestige of the Trinity in the world around us. Perhaps treating nature like creation will remind us that there is a Creator.

Sincerely,

David Russell Mosley