Eastertide

15 April 2019

On the Edge of Elfland

Concord, NH

Dearest Readers,

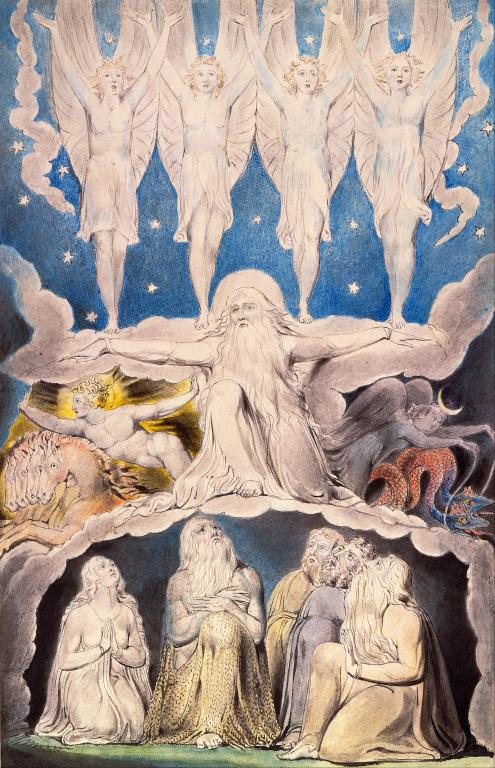

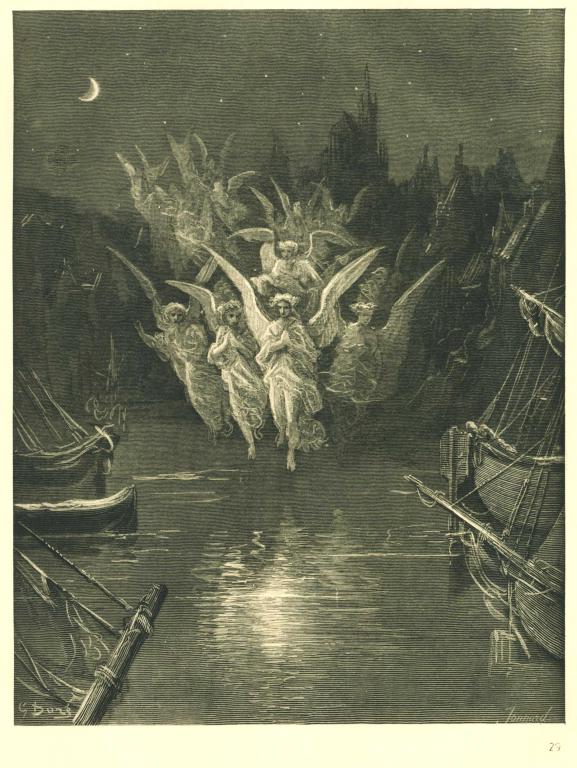

Recently, I finished reading Malcolm Guite’s Mariner: A Voyage with Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The book itself is a heavy one, weighing (with notes, bibliography, and index) at 471 pages. It is, in one sense, a biography of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. It gives what any biography should: dates, names, places, and a narrative to direct them all. Any biographer worth their salt knows that a certain theme must be found or constructed in order to make a compelling biography. Otherwise, biographies would be little more than annotated timelines. Similarly, biographers of writers and poets must include some semblance of literary criticism to highlight the writings of their subject. Malcolm Guite, of course, does both. But rather than see those as separate categories, he does them together. Guite’s major argument is this: The Rime of the Ancient Mariner serves as an interpretive key to Coleridge’s life.

Throughout the book, especially in part 2––which takes place after Coleridge has written The Rime of the Ancient Mariner––Guite shows not only how aspects of Coleridge’s life can be mapped onto the poem he first wrote in his twenties, but also how Coleridge began to associate himself with the titular Mariner. Malcolm’s examples are fascinating and compelling. For Guite, part of this key revolves around opium. According to Guite, many have seen Coleridge as a poetic genius whose genius was enlivened by his use of opium. But Coleridge himself says otherwise. In his notebooks and some of his letters, Coleridge shows that opium is keeping him from his work. And Guite pulls no punches. This is not simple hero-worship. Coleridge appears warts and all, and we see not an albatross but a poppy around his neck.

I could, and likely will, write more about the book itself, but I want to move in a slightly different direction. In reading Guite’s account of Coleridge, I have been shocked by certain striking similarities between aspects of Coleridge’s life and my own. Now, this may come off as more grandiose than I mean it to. I don’t mean to imply that I am as great a poet or writer or philosopher as Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Nor do I mean that I have aspirations to his level of fame. Rather, I mean I can see myself in Coleridge.

Not unlike Coleridge, my upbringing was uncommon. I suffered no death of parents as a boy, nor was I sent off to a fancy school (nor did anyone expect me at the time to become a minister). But, like the young Coleridge, I was at home with adults and could keep them entertained, yes, but also often keep up with their conversations, voicing my own opinion. What is more, I was adopted at a young age (as I have mentioned before) by my paternal grandparents causing my upbringing to be out of the ordinary.

The other small similarities, Coleridge’s fondness for long walks in nature, his habit of keeping and drafting in notebooks, the pain in his knee (caused by rheumatism) which initially caused his turn to laudanum. All, in one form or another, I share. The painful legs and knees is the most uncanny, though I do not know the cause of my pain. Yet it is Coleridge’s addiction and even some of his solutions for it that is most striking.

I should say quickly I have no addiction to any substance. I use nothing illegal nor do I use anything legal illegally. My own addiction or perhaps compulsions are of a more spiritual nature, but they nevertheless lead to many of the same results and stem from similar hurts. I have always struggled with depression and this can turn me to my sins, so I can feel something, anything, other than the oppressive weight of depression. I often have trouble sleeping. My wife has even suggested that I may be having mini-panic attacks at night as my heart races and I cannot find sleep. But I have also finally realized, thanks to Guite and Coleridge, that my turns inward, to self, have drastically reduced my creative and scholarly output. Writing is one of the first things to go as I turn to my compulsions and reading follows as well. Yet, just as it was for Coleridge, these things serve as part of the cure.

I am not often this publicly transparent (and I hope I have been opaque enough that you only have vague hints of what I mean about myself). But I feel I had to share the spiritual effect Guite’s Mariner and Coleridge’s life have had on me. I have been in so many ways “a wiser and sadder man” since I finished this book. I pray that having been stopped by the “grey-beard loon” (and I’ll let you decide if he is Malcolm himself or Coleridge or both) I will learn from Coleridge’s mistakes and his triumphs. And I pray that others in a similar state take up Guite’s book, preferably with a copy of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner near at hand, so too will find themselves transformed.

Sincerely,

David Russell Mosley