Recently, Dr. John Wentworth, professor of physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, argued that regardless of future advances, science will likely never discover whether the supernatural exists. He said,”almost always, our research raises more questions than it answers, therefore the question of God’s existence just isn’t scientifically testable.”

If you are religious, how does reading that make you feel about the validity of your religious beliefs? OK, so how about this version:

Recently, Dr. John Wentworth, professor of physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology argued that yes, one day science will be able to shed light on whether the supernatural exists. He said, “Eventually, we may be able to test scientifically whether or not God exists”

Of course, neither is true. Dr Wentworth is an invention, created for the purposes of a study by Justin Friesen (now at York University, Toronto) and colleagues.

When they gave expanded versions over those stories to a group of 103 American adults, they found that those who were highly religious reported stronger religious convictions after they read that science cannot disprove the existence of god

That seems an odd result, but the researchers reckoned it might be linked to a fundamental psychological drive that underpins religious and similar beliefs. Specifically, when people feel threatened or insecure, they latch on to beliefs they feel to be unshakeable.

To test this idea, they ran a similar experiment on a group of Canadian undergrads who were all at least slightly religious. This time, the news stories they were given to read were about the discovery of the Higgs Boson.

Half of them read that this discovery undermined religious belief (so their beliefs were threatened), while the other read that the results were consistent with religious beliefs.

Then, after giving them a few meaningless tasks so they wouldn’t guess the purpose of the study, they asked them about different reasons for believing in god. Most were unfalsifiable, such as “Living a moral life would be impossible without God”. But some were falsifiable, for example “Historical and archaeological evidence shows how God intervened in the world”.

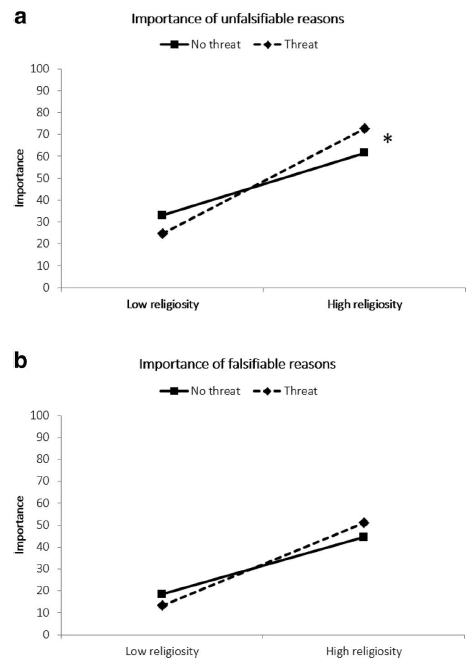

Take a look at the graphs below, and I’ll walk you through them.

What’s shown is how important the students rated the unfalsifiable beliefs (top panel) and falsifiable beliefs (bottom panel). First think to note is that the basic pattern is the same in both panels.

Unlike the highly religious, students who were not very religious did not rate any of the reasons for belief as very compelling. But both the highly religious and the less religious rated the unfalsifiable beliefs as more compelling than the falsifiable ones.

When their beliefs were threatened (dotted line), the highly religious rate both kinds of reasons as more compelling, while the opposite happened with the less religious. The differences are statistically significant, but the trend is interesting anyway.

But the biggest increase was for the ratings the highly religious gave to unfalsifiable reasons for belief. When they felt their beliefs were threatened by evidence, they suddenly found unfalsifiable beliefs significantly more compelling.

Friesen and colleagues point out that, on their own, these data are not conclusive. It might be that the core beliefs of religion are unfalsifiable, and what we’re seeing here is simply people clinging to core beliefs when their belief system is threatened.

But they did similar experiments look at politics and found that, here too, people prefer unfalsifiable beliefs when they are challenged in some fundamental way.

They concluded that these beliefs, more than logic or reason, appeal to fundamental issues of the human condition. At at they end of the day, holding on to these fundamental issues is more important than fixating on reality:

We suggest that when people turn to unfalsifiability, it is because these “practical” issues—for us, existential motives—like having positive self-worth, being a valued group member, or obtaining symbolic immortality, have temporarily trumped questions of belief accuracy or testability.

![]() Friesen, J., Campbell, T., & Kay, A. (2014). The Psychological Advantage of Unfalsifiability: The Appeal of Untestable Religious and Political Ideologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology DOI: 10.1037/pspp0000018

Friesen, J., Campbell, T., & Kay, A. (2014). The Psychological Advantage of Unfalsifiability: The Appeal of Untestable Religious and Political Ideologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology DOI: 10.1037/pspp0000018

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.