“When we define, we seem in danger of circumscribing nature within the bounds of our own notions…” –Edmund Burke

“Poetry is the mother-tongue of the human race.” –Johann Georg Hamann

Given in explanation of the above title is the illustration of two football players recalling with boisterous self-congratulation the events of a recent win. While speaking the players make exaggerated gestures, describing the size of one’s would-be tackler as “big as a gorilla” and the other’s stretching the ball over the goal line as with an arm “like rubber”. Rhetoric of this manner is of course not surprising of a person whose sex is male, whose stage of social development is adolescent, and whose recreational interests in turn bear the title of athlete. The shared genus of the two, assumingly valid within the webs of a specifically Western social taxonomy, yields a mild appraisal of their speech’s propriety in the context of casual small-town conversation.

To be sure, one could not expect a conversation of similar tone and content to occur, say, between two dignitaries brokering a treaty. Nevertheless, the linguistic commonality between the speech of athletes and dignitaries, as it is between all kinds of speakers, is the intent to persuade. When the athlete cloaks his experience in the language of phenomenology, he does so not to entertain or to make a moral import, but to instead predicate about the event as it was to him and therefore as it should be understood by others. The core axiom of all speech, therefore, is that the world as-is is hopelessly unintelligible without the means of language to make meaning from the brute fact of action. Thus is the task of language, to capture the nature of a thing or action in the body of useful utterances and symbols. Thus also is the primitive quality of poetry, unavoidable in all speech, so long as speech exists to persuade one of another’s private meaning overlay as that which is worthy to occupy the public memory.

All speech proceeds with the assumption that one’s perception of a thing is most true to its nature, which is to say, most accurate in its relation to reality. Discourse, then, occurs when there exists the desire to persuade another of one’s consciousness as that which is most true. This persuasion proceeds with ease as with the verbal gloats of athletes, and also amidst staunch resistance as between two officials from rival countries. Whatever the setting, where there is speech, so there is too a poetry that makes its attempts at truth within a shared definition set of what is.

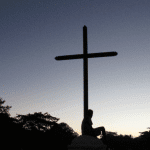

That said, there is within the prevailing evangelical culture a lost grip upon its poetry as a vehicle of revelation. Assumed here is that one even thinly immersed in the staple of church speech will recognize the usual assertions about the reality of God as he is revealed in the here-and-now, e.g., like a fire, like a father, like a shepherd. The use of this poetry proceeds from the common assumption that God as Creator has manufactured earth-bound artifacts to accommodate humankind’s general welfare of understanding, guiding them along a process to “know” him on the way to “personal relationship”. One can look upon fire, fathers, and shepherds, it is insisted, and in each see God’s nature as of uniformly amiable investment in the care and quality of his people’s lives.

The pitfall of this assumption is that God’s behavior within the current order is given to tired prediction. As is commonly declared within the evangelical worship setting, the voice of God is so obvious to be heard in the quiet of an abandoned wood as it was from a thunderous body of tumult, and so certain to be obeyed for matters of career progression as it was for matters of prophetic commission and unreasonable mandate. When deconstructing the speech of the Bible of its fundamental persuasion, the gravity of its content meets something of lesser majesty than what is afforded by a teenage football hero to his very little small-town victory. God in the quiet wood is the poetry of polite perspective, demanding nothings of its hearers, whereas the teenage athlete speaks with greater ambition, insisting that those hearing recall his efforts as a miraculous interruption of physics.

The challenge, then, for a culture whose poetry survives as a time-protected currency, is that a lost primitive must be recovered. That is, when the authors wrote of God as fire, as father, as shepherd, and as one with qualities of faithfulness, justice, and goodness, they did so to persuade audiences of God’s new ontological break from the process of known behavior. This was to impress upon the public consciousness a new convention of how God acts within his own story. In the example of Hagar, her encounter concludes with God bearing the name of El-Roi. He is the God who is seeing of her affliction, and so by Hagar’s speech her experience survives beyond the brute fact of private encounter to become corporate convention.

Given Hagar’s example, one sees that God’s activity is not bound to expectation, and by acknowledging his right to unpredictability, God becomes truly present in a poetry that is as careful in its manufacture as it is persuasive in its aesthetic. How Christians think and talk about God must be uniquely Christian, which is not a quality of blind submission to usual rhetorical templates, but is instead a necessary output of an impassioned intellect. This intellect has answered the question of whether or not God is, speaking beyond extraneous critique as the only base of linguistic knowledge upon which God is made intelligible.

Pregnant within the language about God is infinite possibility, which like God is without limits to destroy or create. Until the church recovers her grip on the primitive necessity of poetry, her language will become reactionary to extraneous critique. Under the guise of a “seeker-friendly” presentation, the Sunday morning experience seeks to endear itself to a staunchly unbelieving culture, advertising a self-effacing quality of conviction, lest the claims of such convictions make upon reality become too public. Rhetoric of this manner is not responsible to the Christian’s basic confession as a political and historical affront, saying there are no saving systems apart from the looming rule of God, which will eventuate in the person of Jesus the Christ who was killed, who was resurrected and ascended, and whose appearance is imminent to collapse the current order. By stretching less tyrannizing and politically unthreatening metaphors over worship manifestations of its canon, the church repackages episodes of stark mystery and discomfort as non-essential to the character of God, receiving its boldest poetics as ostensibly a body of soul-directing lies, useful for instruction only as supposed benchmarks of humankind’s evolving consciousness of divinity.

Whether seeker-friendly, progressive, non-denominational, or by another neologism of new-wave distinction, Christian communities speak of a Scripture more agreeable as to be less obnoxious within the larger sphere of religion’s sociology. This is due in part to the lost art of its rhetoric, as theology students are not trained to make an argument but to keep an argument from being pressured out of its public utility. It is therefore by a revisited observation of the boisterous teenage braggarts that the young theologian can begin to know the core import of Christian profession: what God has done, is doing, and will do is first-person, and any claim to the contrary is of a lower reality overlay on which the Kingdom of Heaven will become borne out of concept and into hard fact.

Thus when speaking with the poetry of faith, the boldness of one’s symbols must meet the audacity of things hoped-for, must proceed from a believing nucleus, or else he or she speaks of a Christianity that expects nothing of itself than what is insisted for it. That Christ mandated a universal prayer of ‘thy Kingdom come’ announced that his church manages its own affairs. She does so by guarding her language as that which was made flesh, which dwelt among us, and which is not given to the critique of non-belief. So the blade of her speech must not become blunted to become immune from giving offense. For offense will remain where the power of life’s definitions is of an embattled perception of what is.

Reverend Tom is an anonymous writer